For many prisoners, the moment their enemy captures them marks the beginning of the end of their war. Others see it as a new phase. The latter was the case for Medal of Honor recipient James Stockdale. When he was captured in North Vietnam in 1965 the honor of leading the POW resistance fell to him. As the senior naval officer, he took his role seriously.

A Stellar Career

James Stockdale was born on September 23, 1923, in Illinois. Coming of age as the United States was embroiled in WWII Stockdale sought to do his duty as men of his age did. In 1943 he enrolled in the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland emerging as a Naval Officer in 1946 – too late to see action in WWII. Over the next three years, he served onboard various US Navy vessels.

In June 1949 Stockdale was accepted for flight training, and in January 1954 he joined the US Naval Test Pilot School and remained a test pilot until 1957. In 1959 the US Navy sent him to Stanford University where in 1962 he graduated with a Master of Arts in International Relations.

In August 1964, Stockdale was commander of Fighter Squadron VF-51 onboard the USS Ticonderoga conducting operations off the coast of Vietnam in the Tonkin Gulf. On August 2, US Naval ships engaged with three North Vietnamese torpedo patrol boats and Stockdale assisted in the fight. Strafing the North Vietnamese vessels, Stockdale gained his first experience of combat.

From Gulf of Tonkin to POW

On August 4 in the same area, US Navy ships reported three high-speed vessels heading towards their location. Stockdale was again in his aircraft, watching the battle from above. He later recalled the incident saying “there was nothing there but black water and American firepower.” Circling above Stockdale could see no enemy presence. However, President Johnson called for retaliation and ordered bombing raids on North Vietnamese military targets.

By 1965, Stockdale was regularly flying combat missions over North Vietnam. On September 9, his Skyhawk plane was disabled by enemy fire. He ejected and parachuted safely to the ground, but villagers and soldiers were waiting. He was severely beaten, and his life as a POW began. He was taken to the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” where he began his organized resistance.

Torture was a regular occurrence. Prisoners were routinely denied medical care and the more the prisoners resisted, the more severe the punishments became. Stockdale created a code of conduct as he was the senior naval officer for all the prisoners. It oversaw their processes for resisting torture, secret communications, and general behavior. Leading by example, Stockdale gave his captors the worst he could in his situation.

No Surrender

In the summer of 1969, Stockdale was locked in a stall with leg irons where he was routinely beaten and tortured. Due to his naval rank, the North Vietnamese thought he would be useful for propaganda. When told he was to be paraded in public, Stockdale slit his head with a razor to prevent his captors from doing so. When they tried to put a hat on his head, Stockdale beat himself in the face with a stool until he was unrecognizable. At one point to avoid incriminating his fellow prisoners he slit his wrists so they could not torture him into a confession.

Identified as a resistance leader, Stockdale was put in solitary confinement. He was incarcerated in a windowless 3-foot by 9-foot concrete cell with a light bulb on continually and locked in leg irons at night.

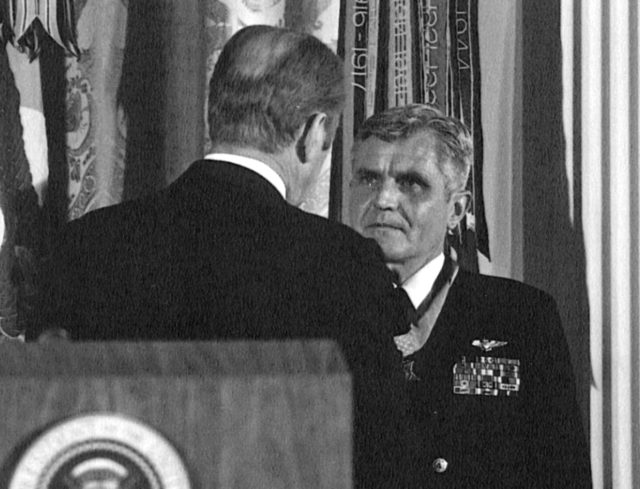

Stockdale survived. He was finally released on February 12, 1973. Due to the torture and abuse he had sustained, Stockdale could barely walk. For his courage and actions during those seven long years and refusal to quit James Stockdale was awarded the nation’s highest military honor.

Despite his debilitated physical condition, the Navy allowed Stockdale to remain in service until he retired in 1979 as a Vice Admiral. He continued working in academic work and gained public attention when he had a shot at the Vice Presidency of the United States running with Ross Perot in 1992.

For many people, it was their introduction to the man the guards and fellow prisoners of the Hanoi Hilton knew well. His service and resistance in Vietnam had been excellent and was in keeping with the best of military tradition for all to see.