After Nazi Germany was defeated in May 1945, the Empire of Greater Japan was the only obstacle to ending the Second World War. But the Japanese were obviously not ready for peace negotiations and surrender.

Kamikazes were ready to fight to the last and die for their ideals. The Japanese authorities also believed that the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact would save them from an invasion by the Red Army.

The United States decided to use radical methods to force the Japanese to surrender, dropping atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

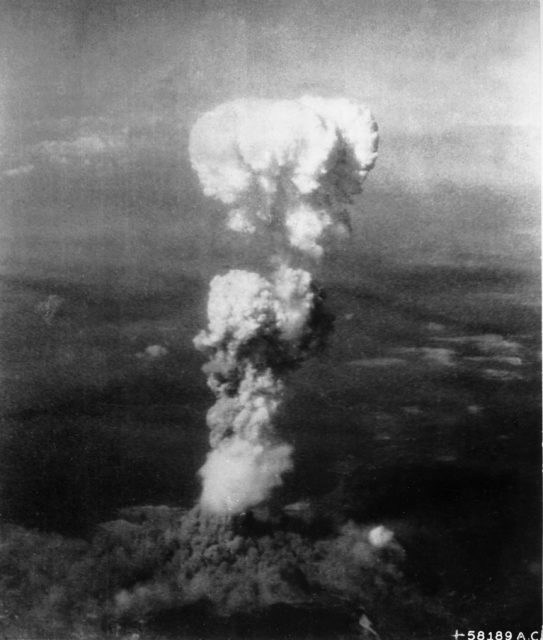

On August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Despite the scale of destruction and a large number of casualties, the Japanese refused to enter into peace negotiations and continued the war.

After that, Truman stated that “If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

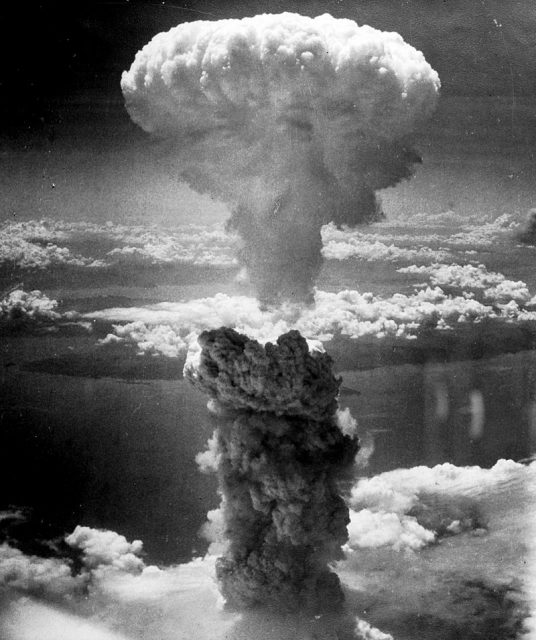

The Japanese were forced to reassess their situation on August 9, when the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. That same day the Soviet Union, which had declared war on Japan on August 8, began hostilities.

In turn, the United States considered dropping a third atomic bomb on Japan. The next bomb should have been ready for use after August 17-18. At the same time, there were discussions about the need to postpone the use of bombs until Operation Downfall, the expected invasion of the Japanese islands, began.

Emperor Hirohito found himself in a bind. The war ministers who had assured him that the United States did not have weapons of colossal power had obviously made a mistake.

Soon the Japanese emperor made a statement, saying: “Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.” He called on the Japanese to “endure the unendurable.”

However, some of Japan’s leaders were willing to continue the war, for several reasons. First, they trusted in the past of the country and declared that Japan had never lost a war. Thus, the idea of capitulation and occupation similar to what had occurred in Germany was for the Japanese a shame worse than death.

Secondly, the Japanese Empire still had thousands of aircraft and small boats left that could be used in suicide missions to continue the war. The fact is that such people rarely surrendered alive.

On the night of 14-15 August 1945, officers of the Ministry of the Army and employees of the Imperial Guard attempted a military coup to prevent a surrender. They had planned a series of desperate measures, including murder, attempting to falsify an imperial decree, and putting Hirohito under house arrest.

The coup attempt ended in failure, and all the conspirators committed suicide. As a result, preparations for the surrender continued as planned. Hirohito addressed the nation, and in this speech renounced his divine nature. His speech marked the first time in history that the Japanese people heard the voice of their emperor on the radio.

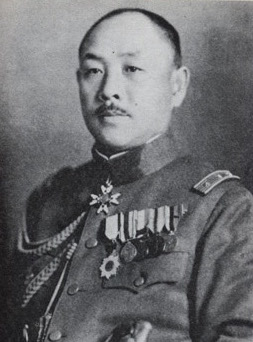

After the decision to surrender and the rapid advance of Soviet troops deep into Manchuria, a wave of suicides occurred throughout Japan. Many government and military officials committed suicide by means of hara-kiri. Abandoning the traditional hara-kiri, Minister of War Korechika Anami shot himself. His suicide note read: “I—with my death—humbly apologize to the Emperor for the great crime.”

On August 15 and 16, many Japanese soldiers ended their lives. In addition, more than 100 American prisoners of war, as well as many Australian and British prisoners of war and interned civilians, were killed on these days. This was done to kill witnesses to the atrocities committed by the camp guards.

At the Batu Lintang camp in Borneo, orders were found which called for the killing of about 2,000 prisoners of war and civilians on September 15, 1945. However, the camp was liberated 4 days before the orders were to be carried out.

The square in front of the imperial palace became a place of voluntary execution. A Soviet diplomat in Japan, Mikhail Ivanov, recalled, “There were new bodies on the palace square almost every day.

It was risky to get close to the place of [suicide preparations] because the person committing it comes into a state of extreme agitation and loses control of himself. But still, I ventured into the square to see this horrible spectacle with my own eyes.”

Often the suicidal person was accompanied by friends or relatives, and then, “Separating from the group that came with him, he stood silently for some time or sat down in a traditional formal posture, turning his face to the imperial palace, then with a decisive sword movement he ripped open his stomach.”

There is also a known case of a mass suicide of islanders jumping into the sea from a high cliff on Saipan. Currently, this place is called “Suicide Cliff.”

The Imperial Army had disseminated propaganda among the local population, claiming that all the Japanese who were captured by the Americans would be subjected to merciless torture and killed.

American soldiers watched whole families jump into the water from an 820 feet (250 meters) high cliff near Marpi Point, the northernmost point of Saipan Island. First, the older children helped the younger ones jump, then the older ones were helped by the parents, who then jumped themselves. As they fell into the sea, the inhabitants of the island shouted: “Tennōheika Banzai” which means, “Long live His Majesty the Emperor.”

Currently, this place is a Buddhist monument and memorial to the victims.

As they pushed forward in the Pacific, island by island, American troops continued to testify about the suicides of Japanese soldiers and civilians.

A Japanese survivor, Kinjo Shigeaki, said, “Back in those days of 100 [sic] million Japanese citizens… being prepared to fight to the very last man, everybody was prepared for death. The doctrine of total obedience to the Emperor emphasized death and made light of life.”