Throughout the Second World War, the Allies tried to spy on Hitler and his generals. They went to extraordinary lengths to understand what the Führer was thinking, using intercepted messages, intelligence from inside Germany, and the advanced decryption facilities at Bletchley Park.

Ironically, some of their best intelligence on Hitler’s thinking came not from spying on the Germans but on their allies, the Japanese.

Baron Oshima

The groundwork for Baron Hiroshi Oshima’s role as an intelligence source was laid in 1934 when he arrived in Berlin to act as Japanese Military Attaché. An officer and a diplomat, Oshima quickly established good relationships with German officers and members of the Nazi party, who had risen to power in Germany the year before.

Oshima’s political philosophy was a good fit with that of the Nazis. He soon gained the ear of Hitler, becoming the Führer’s favored representative of Japan.

The alliance of Germany, Japan, and Italy put Oshima in a powerful position. He was withdrawn to Tokyo in 1939 but returned to Berlin a year later, this time as ambassador.

Almost immediately, Oshima began sending reports back to Japan about the German leader’s plans.

As the war progressed and the Japanese impressed Hitler with successes in Asia and the Pacific, Oshima gained ever greater trust and access to the inner workings of the Nazi war machine. He was central to discussions about how German and Japanese forces could link up through the Middle East.

Oshima was committed to the Axis cause and never betrayed it. Yet he became one of the Allies’ best sources of intelligence on the Germans.

Reading Oshima

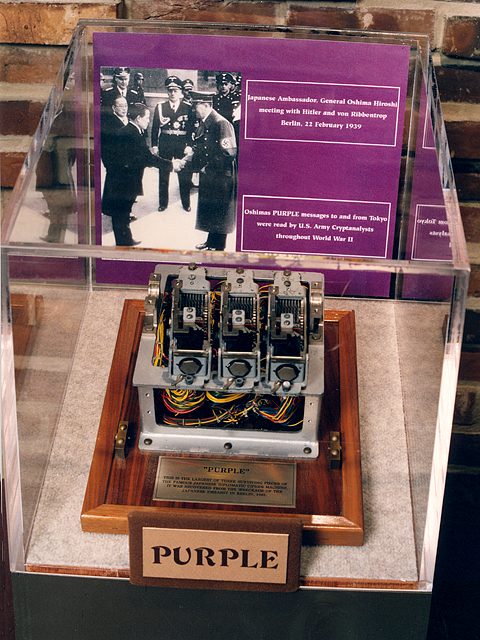

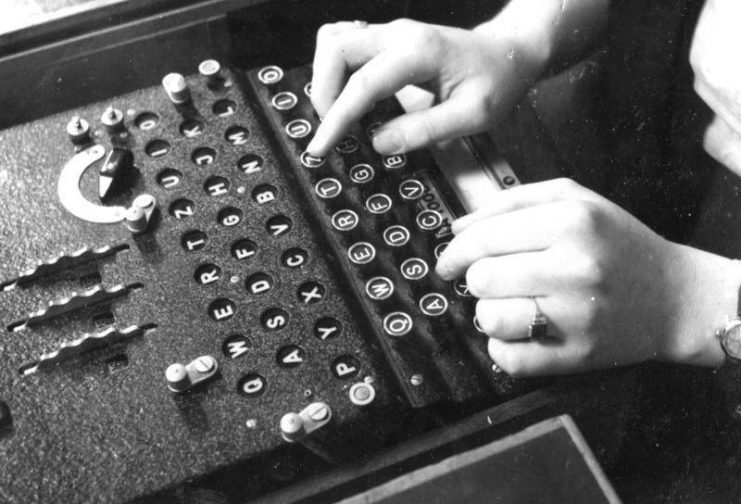

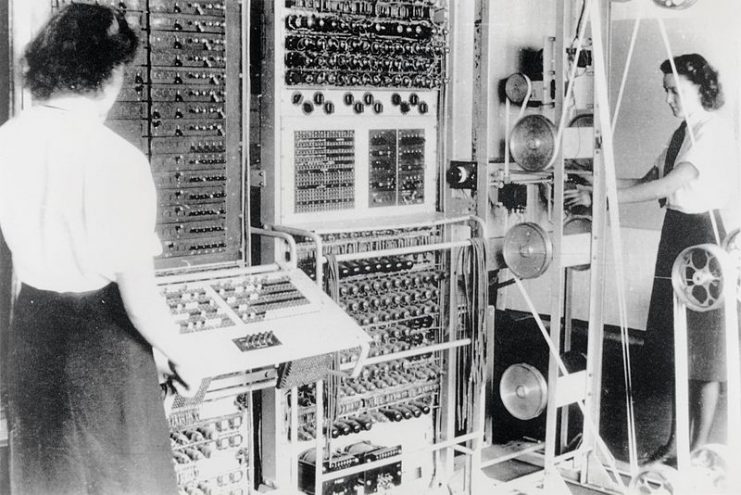

This intelligence came through Magic, the U.S. military’s cryptanalysis program.

Even before they entered the war, the Americans were working on intercepting and decoding the signals of the Axis powers. They broke the Japanese diplomatic codes in 1940, while Oshima was still in Tokyo. By the time he returned to Berlin late that year, they were in a position to read his messages.

Oshima’s diligence and intelligence now became tools of his nation’s enemies. When he became interested in an issue, whether it was jet fighter technology or the defenses of France, he took the time to properly research it, gathering pages of detailed information and sending them home.

Little did he realize that these reports were being read in the United States.

Depth and Breadth of Intelligence

Oshima’s reports covered a wide range of military issues. Though other Japanese signals were more useful for fighting the Japanese themselves, his insights proved of value to the Allies.

One of the first examples of this came in the summer of 1941. Reading Oshima’s messages, American intelligence officers discovered that Germany was planning an extraordinary action – attacking its ally, the Soviet Union.

The U.S. had not yet joined the war, but that didn’t stop the American government using the information. Together with other intercepts, it provided the British with evidence they could present to the Soviets, trying to bring them into the war on the Allied side.

Despite the evidence, Stalin refused to believe that Hitler was turning against him. He ignored the warnings the Oshima intelligence provided and was caught by surprise when Germany invaded in June.

By the spring of 1944, Germany was developing its first jet fighters. This was a topic of particular interest to the Japanese government, who wanted to unlock the secrets of jet flight for themselves.

Oshima investigated the German research. Thanks to his many contacts in the military and Nazi party, he was able to learn incredible details, including the speeds, altitudes, and rates of climb of the most advanced aircraft being developed in the world.

And thanks to his messages, the Allies knew exactly what their own jet engineers were competing with.

Though Oshima’s intelligence was good, its use by the Allies was mixed. As they launched increasingly heavy bomber raids to cripple German industry, Oshima reported on the results. This gave the Allies their most unbiased intelligence on the effect of the bombing raids.

But when Oshima said in 1943 that the raids were having little effect, and when he said the following year that German armaments production was in fact increasing, the Allies refused to believe him. First-hand evidence was no match for the biases of Bomber Command.

1944

Oshima’s intelligence became particularly critical in the buildup to D-Day. He took an interest in German defenses along the coast of northern France and sent repeated reports home about this. They covered a huge range of topics – the design of defenses, the number of divisions stationed there, the German command structure, depths of defensive zones, and even the siting of individual guns. It was all incredibly useful for the commanders planning the invasion.

Reports of Oshima’s conversations with Hitler revealed that the Führer had bought into Allied counter-intelligence operations. He did not suspect the real location of the planned Allied landings.

On September 4, 1944, Oshima had his last meeting with Hitler. In it, the German leader revealed that he was planning a large counter-attack in the west. His troops would gather in October and November when poor weather would interfere with Allied aerial reconnaissance. The attack would be launched in late November at the earliest.

Hitler had revealed his plans for the Battle of the Bulge.

What the Allies did with this intelligence is a matter of debate. But whatever happened that December, Oshima’s messages had hugely helped the Allies to win the war.

Read another story from us: Allies Knew About Battle of the Bulge – Why they Ignored Intelligence

Oshima himself would never learn this. Though he did not die until 1975, he still did not live long enough to see Allied intelligence evidence revealed to a horde of excited historians, and through the historians to the public.

From the far side of the world, Japan had unwittingly helped the Allies to win the war in Europe.