While most people know about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, which happened on December 7, 1941, far fewer people know that six months after this surprise attack, Japanese forces actually invaded and occupied US soil for a time.

It was the only instance of a foreign foe occupying American soil over the course of the war, and it happened on the Aleutian Islands, a string of remote islands 1,200 miles off the coast of Alaska.

Despite the fact that the Japanese takeover and occupation of these tiny, sparsely-inhabited islands presented no immediate threat to the continental United States, the fact that a foreign invader was occupying US soil nonetheless struck a smarting blow to US morale. Efforts were quickly underway to retake the islands from the Japanese.

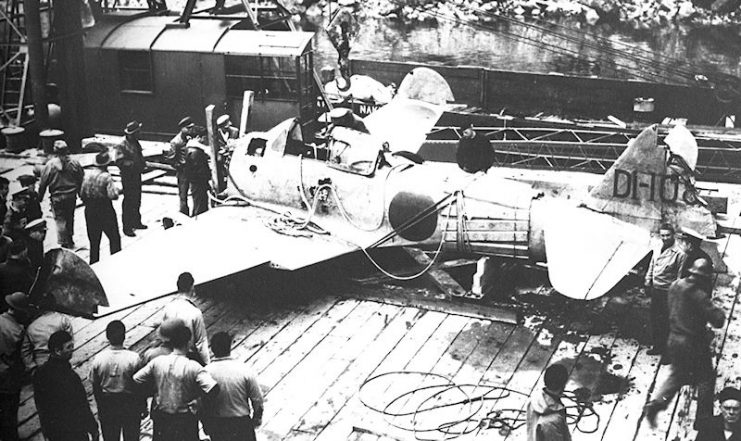

When the Japanese struck their blow against the Aleutian Islands, it came as a relative surprise to the Americans. The Japanese attack began with air strikes on June 3-4, 1942, against Dutch Harbor, where two American military bases were located.

On the 3rd, the Japanese met with stiffer resistance than they had anticipated from the Americans at Dutch Harbor, and this, combined with thick fog, hampered their first attack somewhat. The Japanese attack the following day was better coordinated and far more focused, and resulted in the partial demolition of the hospital, the destruction of a number of oil tanks, and a barracks ship being severely damaged.

Japanese troops then made amphibious landings, first on Kiska Island on June 6th, and then, two hundred miles away, on Attu Island on June 7th.

The local aboriginal population, the Unangax, did not resist the Japanese occupiers, who quickly established garrisons on both Attu and Kiska Islands.

However, while the Japanese initially left the Unangax alone, they began rounding them up in September and sent them to internment camps in Hokkaido.

While the Aleutian Islands did not, superficially at least, appear to have much strategic value, they were symbolically important to both the Japanese and the Americans.

The Japanese may have believed that occupying them would prevent an American attack on Japan by way of these islands. They might also have intended this campaign to distract the US Pacific Fleet.

For their part, the Americans feared that the establishment of a strong Japanese military presence there might precipitate an attack either on Alaska, or a larger series of attacks on the Pacific coast of the United States. Either way, they quickly became determined to get the Japanese off the Aleutians.

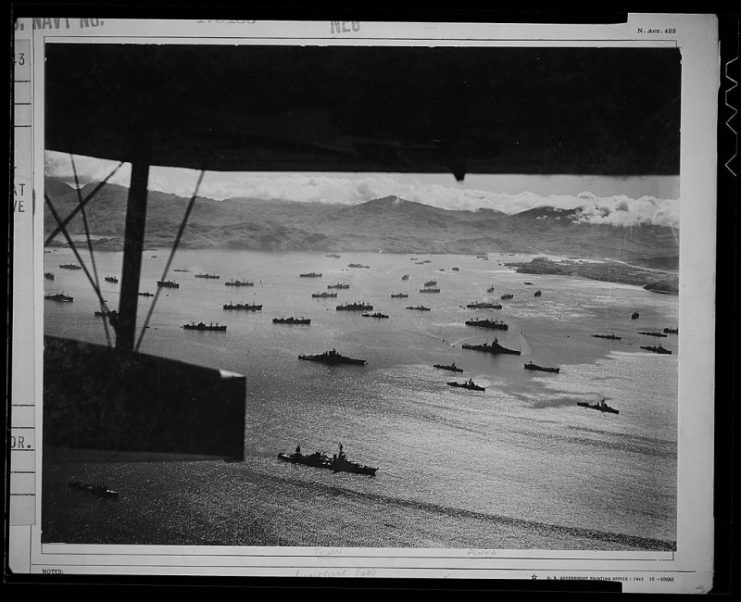

The US Army established an air base on the island of Adak in August 1942. They used this air base to launch bombing raids on the Japanese-occupied island of Kiska, while US Navy submarines and ships began amassing in the waters around the Aleutian Islands.

Over a number of weeks, American naval vessels managed to sink a number of Japanese warships and supply ships in and around Kiska Island.

Specifically, in what became known as the Battle of The Komandorski Islands, ships from the US fleet and the Japanese fleet engaged in an open battle in the Bering Sea.

While the Japanese actually inflicted more damage on the American ships than vice versa, the Japanese retreated from the engagement, leaving the Americans victorious.

This defeat led to Japan abandoning any further attempts to deliver supplies via ship to their ground troops on the islands.

From this point on, supplies would only arrive via submarine, and these came only sporadically, putting the Japanese troops in a vulnerable position.

The next logical phase in retaking the islands from the Japanese occupiers was to attack the islands with ground troops.

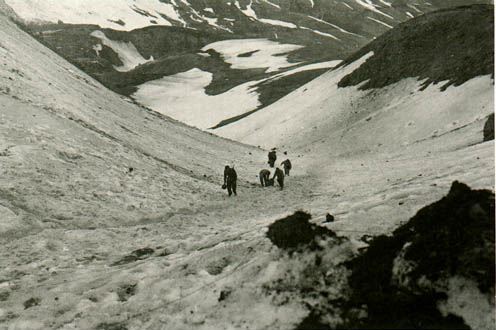

For this – no easy task, considering that the islands were full of ice and snow, and had difficult topographical terrain – Inuit guides and Canadian troops were used to supplement the American infantry forces.

On May 11, 1943, Operation Landcrab was initiated. A number of units from the 7th US Infantry Division made amphibious landings on Attu Island, aided by naval bombardment and air support.

Despite the Japanese defenders being weakened by low supplies and the bombardment they suffered, taking the island from them proved to be an immensely difficult task.

In addition to Japanese attacks from entrenched and well-fortified positions, US troops had to contend with severe cold, with many men suffering from frostbite.

Over the course of two weeks, US forces suffered 3,929 casualties, with 580 dead and 1,148 injured from fighting, with around 1,200 suffering from severe frostbite.

In addition, over 600 died from disease and over 300 were killed by Japanese booby traps. Despite the heavy toll, the Americans managed to push the Japanese back, and by May 29, it was obvious that the battle for the island was won.

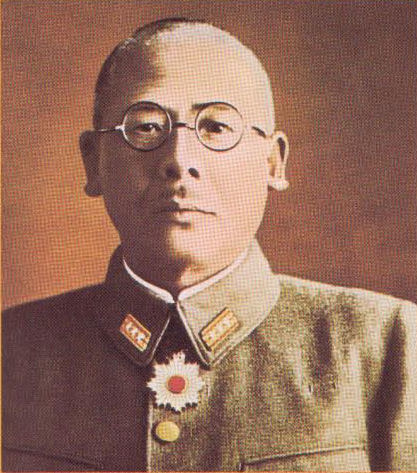

The Japanese, however, had no intention of surrendering. Colonel Yamasaki led what was left of his force in a banzai charge against the Americans that day – one of the largest banzai charges of the war.

The Americans were caught off-guard by the suicidal attack, in which the Japanese managed to break through the front lines.

The fighting was furious and brutal, with no quarter asked or given, and often came down to vicious hand-to-hand combat. By the end of the day almost every single Japanese soldier on the island was dead.

Anticipating a similarly difficult and brutal battle to retake Kiska, a large Canadian-American force was assembled. On August 15, 1943, this force of almost 35,000 troops made an amphibious landing on the island.

After extensive exploration, they found that the Japanese had already abandoned the island, but there were nonetheless casualties, even though no battle was fought. There were 313 Allied casualties, which were caused by Japanese mines, booby traps, friendly fire and frostbite.

The retaking of Kiska Island marked the end of the Battle of the Aleutian Islands – the first and only time that US soil was occupied by a foreign foe during WWII.