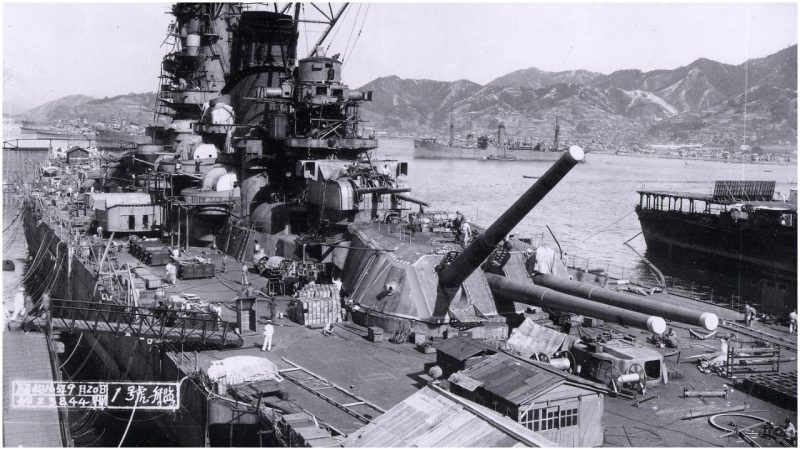

The largest battleships ever built were Yamato and Musashi of the Imperial Japanese Navy. These behemoths were triple the tonnage of some other battleships of their day and each one had three turrets, with three huge 18.1″ guns per turret. They also mounted numerous smaller guns to annihilate secondary targets.

They could outrange and outlast any ship of the line in World War II. Each ship was eventually sunk by aircraft carrier-based planes, proving that the aircraft carrier was now the true image of might in any navy during WWII and beyond.

Age of the Dreadnoughts

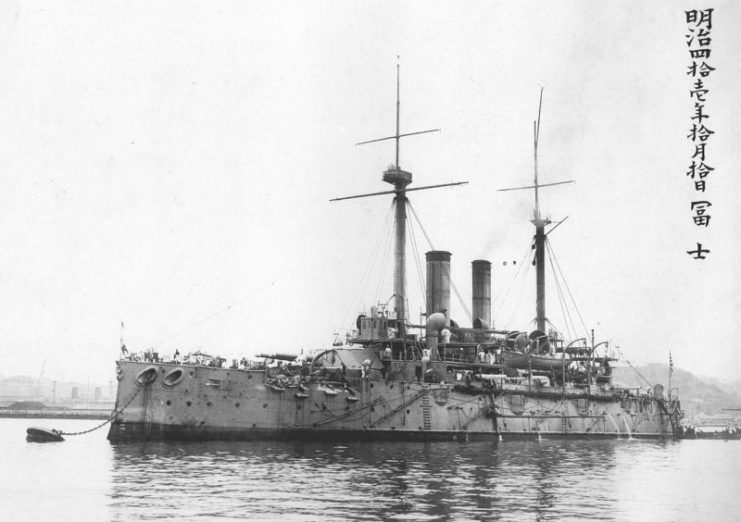

In 1906 the British Royal Navy launched the 18,000 ton HMS Dreadnought. Its revolutionary design heralded the new age of the truly all-powerful “Battleship.”

This new breed of battleships had an all steel design with very large caliber guns in rotating turrets. Despite being heavily armored, their powerful steam turbines enabled them to be incredibly fast, too.

The concept was quickly adopted by every major nation that could afford it. HMS Dreadnought had cost the equivalent of what in 2018 would be roughly 151 million pounds, sparking a huge and expensive arms race, especially between the British and the Germans.

This resulted in these two countries entering World War I in 1914 with large numbers of these cutting edge battleships, and continuing to build more of them in ever increasing numbers throughout the war.

This resulted in even more refined versions, like the Imperial German Battleship SMS Baden, built in 1917, that weighed in at just over 32,000 tons.

But a fundamental flaw with these highly prestigious and costly war machines became apparent: the concern that they were almost too valuable to risk losing in battle.

So for most of the war, neither side felt confident enough to commit them to a full scale battle. The exception was at Jutland in 1916, which was and still is the only large scale battle that involved a large number of battleships.

The battle itself was inconclusive, due to being fought at very long ranges. Both sides were hesitant to commit to a full-blown, head-on battle.

With the end of the war, large numbers of these battleships were scrapped due to their formidable operational costs and the amount of manpower it took to run one of these colossal monsters.

For example, the St. Vincent-class battleship HMS Collingwood needed a crew of 758 to keep her running while at sea. So in 1922, despite being only 12 years old, Collingwood was sold for scrap and sent to the junk yard for disposal.

Throughout the inter-war years, there were several attempts via naval treaties to try to limit the size and number of battleships each major nation could have.

Despite this, technology still helped to further refine the battleship concept. Towards the end of this period, Germany re-established itself as a naval superpower with such ships as the advanced Scharnhorst (1939) and Bismarck (1940). At the same time, the United States and Japan began emerging as two other naval superpowers.

But at this time, questions were starting to be asked regarding whether such a valuable asset could survive in a battle environment that increasingly included aircraft carriers.

For in the 1920’s, the outspoken US Army officer William Mitchell set out to prove air power in the form of aircraft carriers could easily destroy the incredibly costly battleships.

United States Army Air Service.

He did end up proving this to a degree when he sank or badly damaged obsolete battleships in a series of tests. This caused the United States to start to come around to his way of thinking.

So at a time when nations were scaling back the production and development of battleships, why did the Japanese use valuable and scant industrial capacity to build the two largest battleships ever produced?

Yamato-class Battleships

Japanese logic for building such ships was to counter the fact that the U.S. had a numerical superiority in battleships, something Japan could not hope to match. So they concluded that a bigger and better class of battleships would counter the numerical advantage that the Americans had.

Thus, they came up with the Yamato class of Japanese battleships. This class ended up comprising just two ships: Yamato and Musashi.

There was a third ship, but as soon as WWII started, realization dawned that aircraft carriers were what was going to win the Pacific war. Therefore the Japanese decided they would convert the third battleship before it was finished. It would become the Shinano, the largest aircraft carrier in the world at that time.

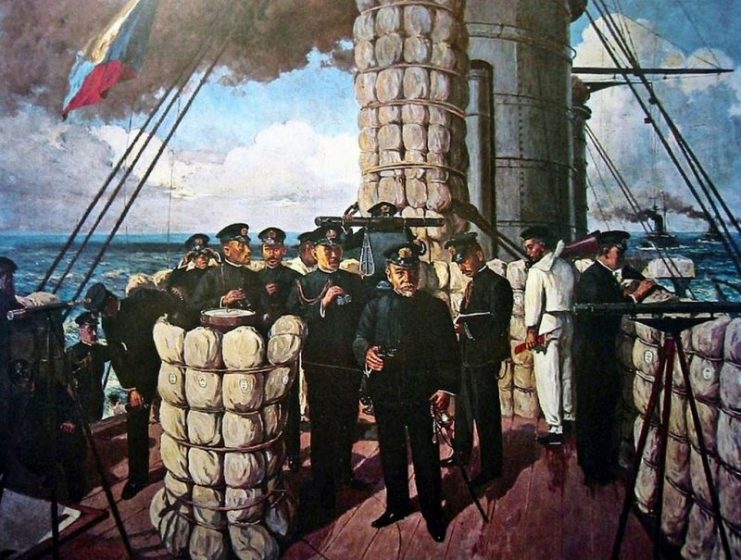

Another reason for going ahead initially with the Yamato class of battleships was Japan’s ingrained respect for such ships. They recalled with pride the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, which became legendary after the Japanese fleet had crushed the Imperial Russian fleet.

At the center of that historic victory was the concept of using battleships that were heavily armored and fast, and that had large caliber main batteries.

| Battle of Tsushima (1905) | ||

| Major Casualties/Losses | Imperial Russia | Japanese Empire |

| Battleships | 7 lost, 4 surrendered | – |

| Cruisers | 4 lost | – |

| Destroyers | 6 lost | – |

| Total Tonnage Sunk | 126,792 tons | *450 tons |

| Killed | Between 4,000 to 6,000 | Around 110 |

| Captured | Nearly 6,000 | – |

*3 torpedo boats sunk

It is easy to see why such a decisive victory might influence thinking in the Japanese Navy for decades to come.

Although the big battleship concept was an important influence on Japanese Navy planning in the inter-war years, nevertheless the Japanese Navy was also forward-thinking, and started to build aircraft carriers as far back as 1921.

During the 1920’s Japan built Hosho, Kaga, and Akagi, and during the 1930’s they built seven more aircraft carriers.

The British raid on the Italian fleet at Taranto in 1940 was said to have influenced Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The latter attack sank or damaged many U.S. warships including four battleships, as well as destroying large numbers of aircraft.

As if Pearl Harbor was not enough to vindicate the belief in the air-power that aircraft carriers could provide, just three days later Japanese aircraft attacked the British Z Force, sinking a battleship and a battlecruiser with very few casualties of their own.

| Early Carrier Air Power Victories | ||||

| Attacker/Target | Date | Attacker’s Aircraft losses | Target’s losses | |

| Battle of Taranto | Great Britain/Italy | Nov 12th 1940 | 2 | 3 Battleships damaged |

| Pearl Harbour | Japan/USA | Dec 7th 1941 | 29 | 4 Battleships sunk 4 Battleships damaged |

| Attack on Force Z | Japan/Great Britain | Dec 10th 1941 | 6 | 1 Battleship Sunk 1 Battlecruiser |

For the rest of the war, the Japanese concentrated on building as many aircraft carriers as it could, as well as converting a number of existing or near completed ships into aircraft carriers. The fact of the matter is after the two Yamato-class battleships were completed, Japan never built another battleship ever again.

As for Yamato and Musashi, the design for these ships had been finalized in 1937, after a protracted and detailed examination of twenty-four very different and modern design proposals.

Yamato was laid down in November 1937 and was commissioned into service on December 16, 1941, just days after Japanese carrier-based planes had successfully attacked both Pearl Harbor and Z Force. Therefore Yamato arrived in service at a time when events were starting to raise questions about the usefulness of battleships.

Yamato‘s sister ship Musashi was laid down in March 1938 and was commissioned into service on August 5, 1942. Thus both ships entered service after each taking over four years to build.

To show you how much naval air warfare had progressed in that short time, in 1937 the British Navy was using 150 mph Blackburn Shark biplane torpedo bombers that could carry an 18-inch torpedo or 1,600 lbs of bombs.

By the time Musashi was commissioned in 1942, the U.S. Navy was using the 275 mph Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber that could be armed with either a 22.5-inch torpedo or 2,000 lbs of bombs.

This rapid aircraft development caught the Yamato-class battleships by surprise. Initially, Yamato had only 28 anti-aircraft guns when commissioned in 1941. The Musashi, commissioned a year later, incorporated lessons learned from recent events regarding air defenses, and came into service with 40 AA guns.

With aircraft carriers now dominating the Pacific theater, by 1945 the Yamato had no less than 166 AA guns!

| Landmark Battleships | |||||||

| Nationality | Year | Tonnage | Main Gun | Length | Crew | Speed | |

| HMS Dreadnought | British | 1906 | 18,410 | 10 x 12 inch | 527 | 750 | 24 mph |

| SMS Baden | German | 1917 | 32,200 | 8 x 15 inch | 590 | 1,271 | 24 mph |

| Bismarck | German | 1941 | 41,700 | 8 x 15inch | 823 | 2,065 | 34mph |

| Yamato | Japanese | 1941 | 65,027 | 9 x 18 inch | 862 | 2,650 | 31 mph |

| South Dakota | American | 1942 | 35,600 | 9 x 16inch | 680 | 2,364 | 31mph |

| *HMS Darling | British | 2009 | 8,500 | 1 x 4.5 inch | 500 | 191 | 35 mph |

| *For comparison The UK largest Major Surface Combat Ship in service today (2018) | |||||||

The Yamato-class ships were truly breathtaking in their scale and armament. When fully loaded they each weighed an incredible 72,000 tonnes and were fitted with the largest guns ever carried by a battleship. Each one had a main armament of 18.1-inch guns capable of firing 3,220-lb shells over 26 miles. Their turrets had armor over 25 inches thick.

The ships had been built in secret and amazingly, the Allies were totally unaware of their existence until 1942. U.S. Intelligence was shocked that ships like this could have been built without their knowledge.

Yamato and Musashi in the war

But the Japanese quickly became afraid to deploy these new battleships, even being reluctant to allow them out to do patrols. The Japanese High Command was forever fearful of Allied submarines or aircraft carriers attacking them. Also later on in the war, there was simply not enough fuel available to run them regularly, so both ships spent most of the war inactive, berthed at various “safe” naval bases.

This fear and hesitation was further reinforced when Yamato was badly damaged by the U.S. submarine Skate in December 1943. Then in March 1944 Musashi was damaged by the U.S. submarine Tunny.

But by late 1944 the Japanese Navy was forced to deploy the battleships, both out of necessity and desperation. Thus Yamato and Musashi participated in the Battle of the Philippines on June 19-20, 1944, but this was primarily a carrier to carrier battle and neither battleship saw any real action.

Then on October 23-26, 1944 Yamato took part in the Battle of Leyte Gulf and for the first time saw real combat. During the battle, Yamato managed to help sink the escort carrier USS Gambier Bay and the destroyer USS Johnston.

But the Yamato herself was badly damaged by aircraft from the U.S. carriers Intrepid and Cabot, though she did manage to return to port.

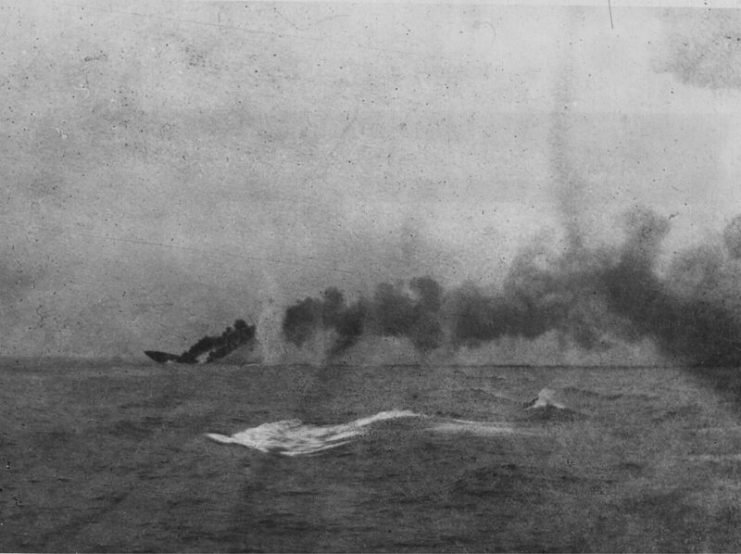

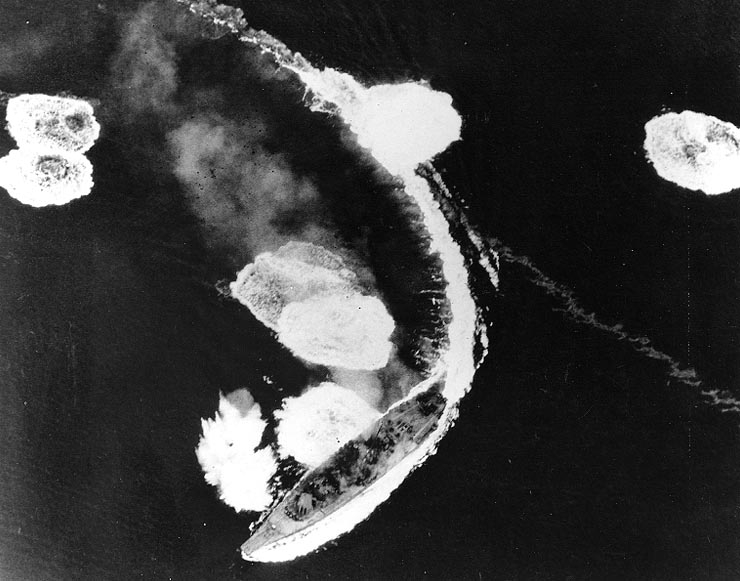

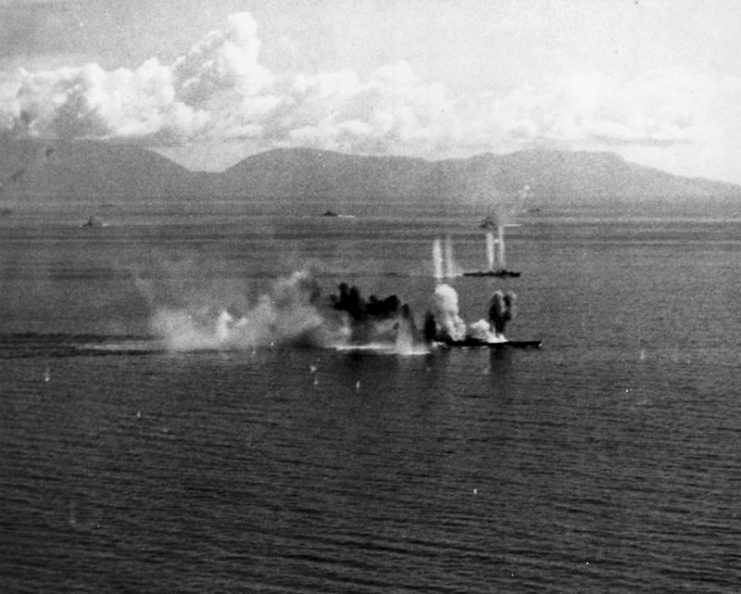

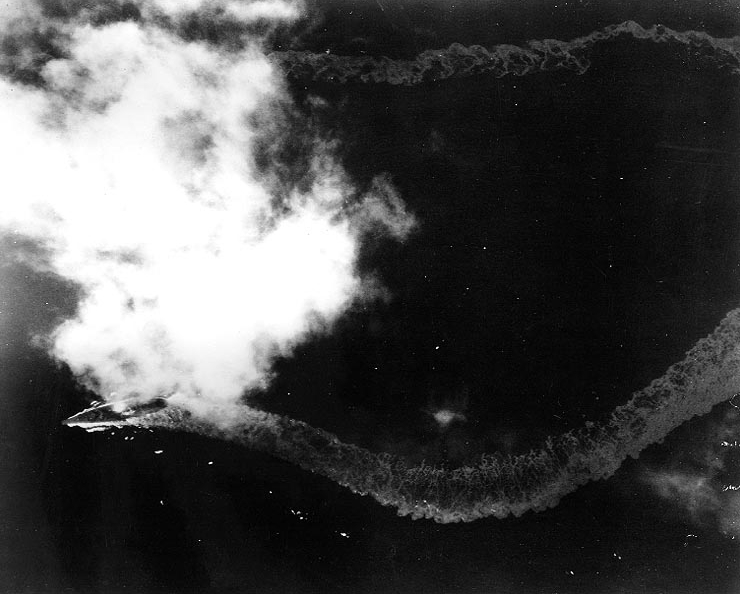

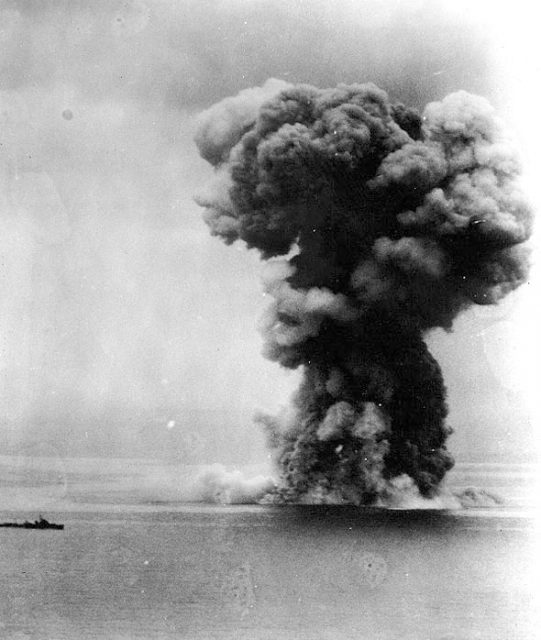

Musashi was less fortunate and was attacked by several waves of aircraft from various aircraft carriers including the Intrepid, Cabot, Essex, Lexington, Enterprise, and Franklin. Finally, after multiple torpedo and bomb hits, the Musashi sank, taking nearly half of her crew of 2,399 men with her. In her short wartime career, Musashi did not sink or damage any Allied shipping.

As for Yamato, it did not venture out again until April 1945, when Nazi Germany was on the eve of surrender in Europe. Japan sent out a large fleet of warships headed by Yamato to attack Allied shipping engaged in the Battle of Okinawa. It was an act of desperation that was almost suicidal since the task force had little to no air cover.

The Americans intercepted the Japanese force with hundreds of bombers and torpedo bombers, launching wave after wave of aerial attacks. It was an onslaught, and it took the Americans just over 100 minutes to sink Yamato. Ninety percent of Yamato’s crew was killed, including fleet commander Vice-Admiral Seiichi Itō.

After WWII battleships were quickly phased out. A few of the United States’ Iowa-class battleships lingered in service on and off until 1992, when the era of the battleship finally faded into history.