Norwegian hero, Joachim Rønneberg, the last of the men who raided the Nazi heavy-water plant in 1943, died on October 21, 2018. He was 99 years old.

In Norway, Rønneberg and the men who accompanied him on the raid were national heroes. They were feted by royalty not only in his native land but in many of the Allied nations. They became the subjects of many books, films, and documentaries.

There are many popular articles written about the raid on the Norsk Hydro heavy-water plant. Some articles suggest that the raid prevented the Nazis from getting the atomic bomb before the Allies and winning the war. This is not the case.

In reality, the Germans were years away from the development of nuclear weapons. It may even be the case that the head scientist of the German nuclear program, Werner Heisenberg, slowed down research and development of the weapon on purpose.

Nevertheless, that does not take away the accomplishment of these men nor discount their bravery on what was code-named Operation Gunnerside.

At the time, and for some years afterward, the few people within the Allied camp who knew about both the German and the Allied efforts to develop atomic weapons believed that Hitler was within a hair’s breadth of getting the bomb first.

No one then or now could be under any illusion about what would have happened if the Nazis had gotten nukes first: millions upon millions more people would have died. At the very least, the Nazis would have controlled Europe, most of the Soviet Union, and the Middle East. Nazi world domination would have been a reality.

The men of the Gunnerside operation and those who sent them on it were terrified that the work being done at the Norsk Hydro plant was integral to the final development of a Nazi A-bomb. To them, the risks could not have been higher. Each man on the raid was fully prepared to die if necessary to achieve the mission.

Joachim Rønneberg was born in August 1919 in Ålesund, in the fjord country of the west coast of Norway, 367 miles northwest of Oslo. Both he and his brother, Erling, were avid outdoors-men, like many Norwegians who live in this beautiful area. These traits would help them greatly during the war.

While Erling did not participate in Gunnerside, he did flee Norway upon German occupation and joined the British Commandos, like his more famous brother. The Rønneberg family were staunchly patriotic Norwegians, and their family had been prominent in Norwegian politics for more than a century.

Joachim and eight friends fled to Scotland on a small boat when the Nazis and their Norwegian collaborators, led by the infamous Vidkun Quisling, came to power. He had been called up for national service in Norway before the war, and so had some military experience. But his specialty was surveying and cartography, not commando tactics.

Once in the UK, he joined one of the many foreign detachments of the Commandos and received the specialized training that made the force elite.

Pre-war intelligence had indicated to the Allied High Command that the Germans were involved in nuclear research. During the first years of the war, intelligence gathering on this German project was of the highest priority. Allied research into nuclear power and weapons also provided a framework for what the Germans must be working on.

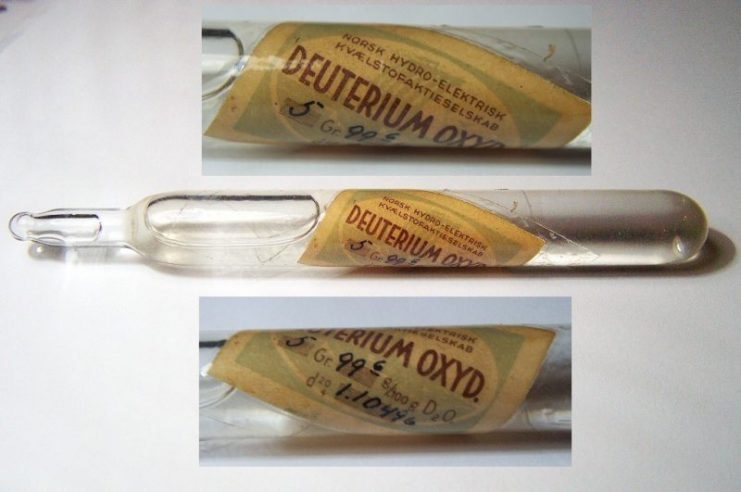

An integral part of the development of the Bomb involved so-called “heavy water,” the informal name for deuterium oxide (D2O). Early work in the development of nuclear power involved the use of graphite to control a potential nuclear chain reaction and the subsequent production of plutonium.

The work was abandoned when graphite was deemed unsuitable for the task of containing a chain reaction for as long as needed. Graphite would have been suitable had the Germans been able to obtain a more purified form, like that which was used in the United States. But instead, the scientists turned to heavy water, which had the potential to be a better moderator.

The history of the Norwegian heavy water plant run by the Norsk Hydro company and its utilization by the Nazis is a long and complicated one: suffice it to say that the plant was the only viable option to get the amount of heavy water needed to equip the Nazis bomb program.

This fact was known to the Allies as well, for French intelligence had purchased much of its existing heavy water production before the war as a way of preventing it from falling into German hands.

Joachim Rønneberg’s operation was actually the second attempt to destroy heavy water production. The first team that had been dropped in had been a disaster.

Operation Freshman had attempted to drop a team of some forty British glider-borne commandos to hit the plant. They were to rendezvous with a previously dropped four-man team of Norwegians who had been collecting information on the plant for some time (under the code-name Operation Grouse).

Unfortunately, both the Halifax bomber and the glider it was towing crashed. Some of the commandos were killed in the crash. The remaining men were captured, interrogated, and executed by the dreaded Gestapo.

Consequently, the Germans knew the Allies were aware of the importance of the Norsk Hydro plant and were actively pursuing plans to knock it out of action.

After the failure of Operation Freshman, there was pressure on the air forces of Britain and the United States to knock out the plant by bombing. Later air raids would do considerable damage to the plant, but only after the use of night bombing, which was not possible in 1943 – the Luftwaffe was still too powerful at that point.

So the Special Operations Executive and other British intelligence services successfully argued for another ground raid, stating that the plant was so well constructed and located that bombing would be unsuccessful.

Rønneberg was put in charge of training the six-man team put together for Gunnerside, and the men were dropped into a snowstorm dozens of miles from the men of Operation Grouse.

After holing up in a cabin on a plateau miles from the plant at Vemork/Ryukan (the two nearest towns), the team then skied to the plant during the night of February 27-28, 1943.

Their target was across a considerable chasm in the rugged landscape covered by heavy snow. The men had discussed hitting the plant by crossing the bridge, but it was too heavily guarded. Rønneberg and the men with him believed they could cross the ravine.

Having successfully crossed during the night, the team approached the plant undetected, despite German guards and 24-hour work shifts. The commandos worked their way inside. Intelligence and pre-war knowledge equipped the men with very exact details of the floor plan.

Once inside, they planted plastic explosives on the heavy water production chambers then fled, leaving behind one Thompson machine gun as evidence that it was Allied troops who carried out the raid, not Norwegian resisters.

They hoped this would prevent the Nazis from carrying out the savage reprisals they were known for.

As the men re-crossed the chasm, their explosives went off, destroying the heavy-water capability of the plant for some time. They believed they had achieved a significant blow to the Nazis’ dreams of an atomic bomb.

Joachim Rønneberg fled to Sweden cross country with four others. Two other men went to Oslo to work with the resistance, and four carried out further action in the central Norwegian area where the plant was located.

One little-known fact about the heavy-water operation was not so uplifting. It did not involve Joachim Rønneberg, but it deserves to be remembered in every recounting of the event.

After later bombing raids convinced the Germans to give up their rebuilding efforts at Norsk Hydro, they wanted to move the supplies they had on hand to Germany before another air raid destroyed what was left. To do this, they had to transport their supply on a ferry across a large Norwegian lake before it could be taken to Germany.

One of the Gunnerside men who remained in the area put together a small team and planted bombs on the ferry. The explosion took the vessel to the bottom, along with the Nazis’ heavy-water.

The men knew that a number of innocent Norwegian civilians would be killed, but they took the unenviable decision to proceed with the bombing anyway, given the consequences if they didn’t.

Rønneberg participated in other highly dangerous commando raids in Norway during the war and took part in its liberation upon the German surrender in 1945.

Read another story from us: Scissorforce: Britain’s WWII Commando Experiment in Norway. Did it Work?

After the war, he took up a career in broadcasting, working for years for the Norwegian state channel, NRK. He also gave speeches and talks to school children about the war so that those years and the sacrifice of so many would not be forgotten.

He was the recipient of many citations not only from Norway but also from the United Kingdom, the United States, and France, all in recognition of his bravery and the importance of the role he played in WWII.