The role of South African troops in the Second World War has sometimes been forgotten, even though they were involved in many of the Allies’ major campaigns. Even less acknowledgment has been given to the role of black South Africans who fought for the Allies.

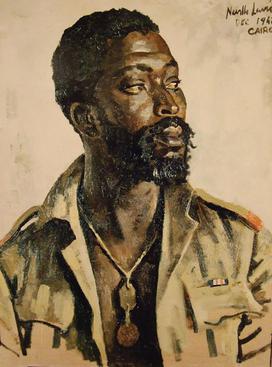

One black South African soldier who particularly deserves remembering is Job Maseko. Despite being a prisoner of war, he managed to sink a German ship with an improvised explosive he had made in a milk tin.

Job Maseko came from a humble background. When the Second World War broke out, he was working as a delivery man in Springs, which is around 30 miles from Johannesburg.

While native Africans were not allowed to enlist in South Africa’s armed forces (the Union Defence Force (UDF) at that time) the need for large numbers of men to fight in the war prompted a change in policy.

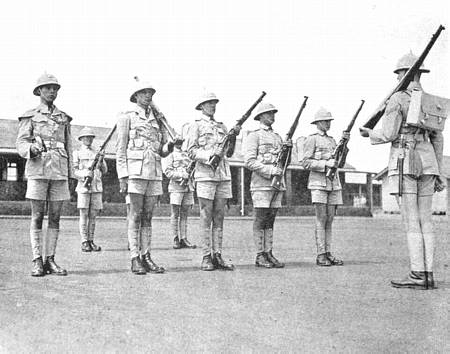

Even though black, Indian, and mixed-race troops were then allowed to enlist from 1940 onwards, their roles were strictly non-combatant. Only the white troops were given military training.

Despite these restrictions, Job Maseko and 77,000 other South African troops of color volunteered to fight the Axis.

Maseko attained the rank of lance-corporal in the UDF’s Native Military Corps and was stationed in North Africa with 10,000 South African troops (of whom around 1,200 were fellow Native Military Corps members) at Tobruk, Libya, in early 1942. By then, the port had been under siege and suffering heavy bombardment by German forces for quite some time.

Initially, the only weapons the African troops of the Native Military Corps were allowed to handle were spears, which they were given while on guard duty. This seemed ludicrous considering that their enemies were armed with machine guns.

However, as Rommel’s Afrika Korps forces closed in and the defense of Tobruk became more desperate, the black soldiers were finally given rifles and allowed to fight alongside their white counterparts.

The Germans could not be resisted though, and with no Allied air support, German Stuka and Ju 88 aircraft bombed the port, while Rommel’s artillery pounded the town and his tanks and infantry advanced.

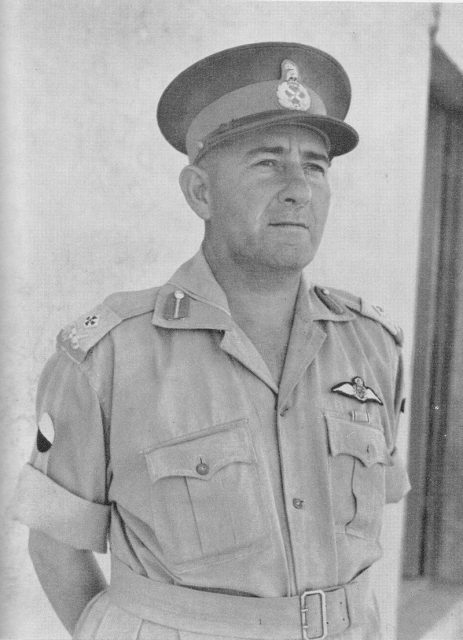

It became clear that Tobruk was going to fall, and the South African commander, General Klopper, surrendered on June 21, 1942. Maseko and the thousands of other South African troops became prisoners of war.

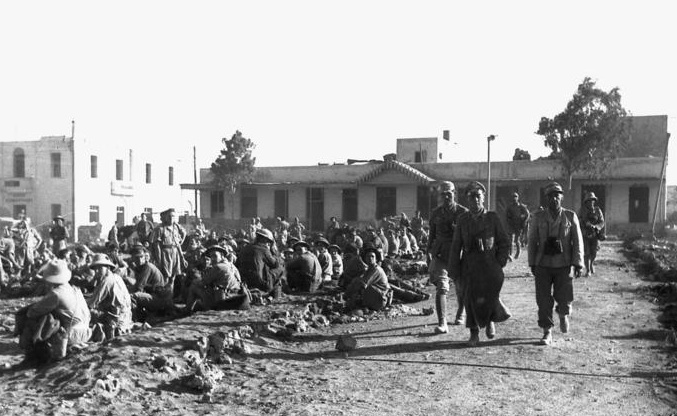

The Germans separated their prisoners by race. The white troops were sent to POW camps in Europe, but the prisoners of color were marched across the desert to an Italian POW camp. There, like many Allied prisoners in various Axis prison camps, they were forced to work as manual laborers under horrific conditions.

Food was strictly rationed, with the prisoners being given a couple of dry cookies every day and some cornmeal porridge which was often infested with weevils. Despite the desert heat, only the minimum quantity of water was given to the prisoners.

The camp commandant, Major Schroeder, was an especially brutal man, and many of the prisoners were regularly beaten and tortured. The guards also took delight in tormenting the prisoners.

On one occasion, Rommel himself visited the camp to inspect it. While inspecting the prisoners, he chose to speak to Job Maseko, asking him how he was being treated in the camp.

With Major Schroeder looking on with hatred and warning in his eyes, a lesser man would likely have lied and said that everything was fine, but Maseko told Rommel exactly how things were for the prisoners. For his daring honesty, he received a long stretch in The Hole – solitary confinement, during which he was tortured.

Part of the prisoners’ forced labor involved loading and unloading supplies from German freight ships in the port. It was during one of these missions that Maseko decided to take revenge against his sadistic captors.

During the last desperate days of Tobruk’s defense, Maseko had learned something of the art of improvised explosive making. While unloading cargo from a German freight ship in the harbor, Maseko got three of his fellow prisoners to distract the German guards while he got busy below deck making a bomb.

Using a box of bullets (from which he extracted the gunpowder), an empty milk tin, and a long fuse, Maseko put together an improvised bomb which he stashed among the barrels of gasoline in the ship’s hold. While he and his fellow prisoners were taking the final load off the ship, Maseko lit the fuse and quietly crept away.

A few minutes later, when Maseko and the other prisoners were returning to the camp, a huge boom ripped through the harbor. The bomb had exploded, along with all of the barrels of fuel in the German ship. Within minutes the ship had sunk, and Maseko’s mission had been successful.

The Germans had no idea who had sunk their ship or how, and Maseko escaped punishment. Maseko later triumphed over his captors again when he escaped from the prison camp.

After finding and repairing an old German radio, he got word of British General Montgomery’s success at El-Alamein. He made his way there, hiking across the desert, to re-join the Allies.

For his heroism, Maseko was presented with the British Military Medal for bravery.

However, there was some controversy about this award. Allegedly, it was recommended that Maseko receive the Victoria Cross, but because of his skin color and South Africa’s racial policies, this was downgraded to the Military Medal.

Sadly, the life of this South African war hero came to a tragic end shortly after the war. Like so many other South African troops of color, the sacrifices he made and the hardship he endured during the war counted for little back home. He returned to menial employment and died in poverty when he was hit by a train in 1952.

It took well over half a century for his deeds to finally be acknowledged, but now several books and a documentary have been made about his life. A number of streets and a school in South Africa have also been named after him.

Now, finally, history has ensured that the courage of Job Maseko will not be forgotten.