Johann Rehbogen, a former enlisted SS soldier who is now accused of being an accessory to murder, has gone on trial.

He was a guard at the Stutthof concentration camp, east of Danzig, from June 1942 to September 1944. He is being tried in juvenile court since he was under 21 during that time period.

The camp held up to 25,000 inmates at any one time, with more than 110,000 passing through its gates during the five years of its operation.

It is estimated that more than 60,000 died there, including some 28,000 Jews.

By June 1944, Jews made up nearly seventy percent of the prisoner population. The camp was liberated by the Red Army on May 9, 1945.

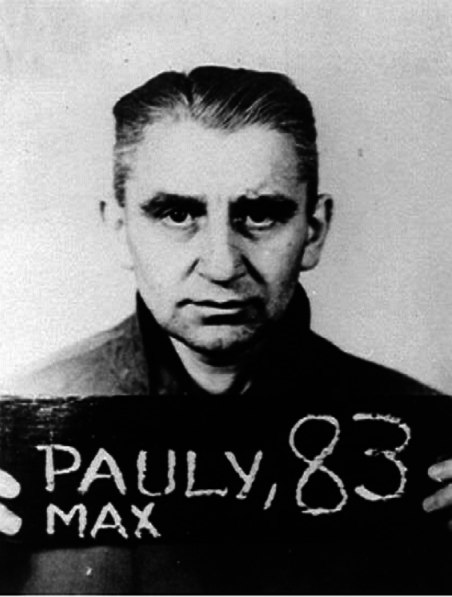

The commandants at the camp, Max Pauly and Paul Werner Hoppe, were in charge of 3,000 SS men and Ukrainian auxiliaries.

Pauly was hanged by the British for other war crimes in Germany on October 8, 1946 and was not tried for crimes at Stutthof.

Hoppe went on the run after the war but was caught, tried, and convicted for accessory to murder in 1955. He was released in 1966 and died in 1974.

Prosecutor Andreas Brendel spelled out the various ways in which inmates were killed. While there was a gas chamber on the site that could accommodate up to 150 people, the Nazis also used injections of gasoline or phenol directly to the heart, or simply exposed them to the harsh Danzig winter to freeze. Some inmates starved to death. The lucky ones were shot.

Rehbogen does not deny serving at the camp during the war but has said to investigators that he had no idea that the murders were happening while he was there. He also denies participating in any such action in the two years he was at Stutthof.

Andreas Tinkl, Rehbogen’s attorney, has said that he expects his client to make a statement to the court, but that a date had still to be scheduled. In deference to the age of the defendant, court time is limited to two hours per day on two non-consecutive days per week.

The Simon Wiesenthal Center has been central in locating twenty witnesses to the atrocities perpetrated at Stutthof.

Relatives of victims and some remaining survivors are expected to also join the trial as co-plaintiffs, as allowed under German law.

Efraim Zuroff is the Center’s “Nazi Hunter-in-Chief.” He defended the need to prosecute such crimes more than seventy years after the event, saying “The passage of time in no way diminishes the guilt of Holocaust perpetrators and old age should not afford protection to those who committed such heinous crimes.”

Indeed, the Nazi War Crimes Office in Ludwigsburg still has many open investigations on its books despite the dwindling number of suspects. In addition to crimes committed at the concentration camps, there are open investigations into surviving members of mobile death squads.

The successful prosecution of John Demjanjuk in 2011 helped boost confidence in the prosecution process for former death camp guards, despite the fact that Demjanjuk died before his appeal could be heard.

Another prosecution, in 2015, of Auschwitz guard Oskar Groening was also successful using the same grounds—that to have been a guard at a death camp was evidence enough that a defendant was guilty of being an accessory.

Where Stutthof differs from Auschwitz is that Stutthof was not set up to be a death camp specifically. Its original purpose was as a forced labor camp. The gas chamber and crematorium were not built until 1943, after Rehbogen had been at the camp for some time. The trial is expected to continue through January 2019.