On September 1, 1939, while German troops were rolling across the border into Poland, their Navy was sent to raid Allied shipping lanes, much as they had in the Great War. One ship, KMS Admiral Graf Spee was already far out into the Atlantic, and ready to commence a campaign of terror which would tie up twenty-three Allied fighting ships, and sink numerous merchant shipping.

The Graf Spee was laid down in 1932, as a replacement for the aging battleship Braunschweig, a WW1 era ship from 1901. The new ship was designed to be a fast, well-armored battlecruiser. Referred to as a Pocket Battleship, she was intended to outmaneuver and outgun almost any ship which she encountered.

Germany had changed significantly during the Graf Spee’s construction. Originally designed for defense, by the Weimar Republic, she was commissioned in January 1936, when Hitler ruled over the country. She was a representative of Nazi Germany; brand new, well armed, and modern. She began her career with sea trials and propaganda patrols.

The Graf Spee first entered military life in the summer of 1936 when she was sent to the coast of Spain. She patrolled the region to prevent foreign intervention in the Spanish Civil War, to ensure no foreign aid reached Republican Spain. Due to the NonIntervention Agreement, this action was legal, but her role there was ironic, considering Germany’s open and enthusiastic support for the fascist Nationalist rebels and their fight.

While it provided experience for her crew, the patrols never led to combat, and the Graf Spee returned to her political role, showing the world the splendor of Nazi Germany. Beneath the veneer of pomp and circumstance, however, the nation was preparing for war.

On August 21, 1939, the Graf Spee left Wilhelmshaven, headed for the Atlantic under the command of Kapitan zur See Hans Langsdorff. By the time war was declared on September 1, she was well on her way to the South Atlantic, and British shipping lanes. At first, her orders were to avoid conflict. Hitler was still entertaining the idea that Britain might not go to Poland’s aid, and he did not wish to antagonize them.

On the 26th, she received orders to begin attacks on shipping. Her Arado floatplane started patrolling past the horizon. Four days later, the plane caught sight of a lone cargo ship, the Clement, from the Booth Steam Ship Company. The Graf Spee gave chase, eager to test their pocket battleship. They caught up with the cargo ship off the coast of Brazil and ordered her to stop. By the laws of war, the captain and chief engineer were taken as prisoners, and the rest of the crew boarded lifeboats before the Graf Spee sank the Clement. Before the ship was sunk, she sent out a signal “RRR,” meaning “I am under attack by a raider.” The Royal Navy was alerted to the Graf Spee’s presence.

On October 5, 1939, twenty-three ships, from the Royal and French Navies were organized into eight groups to hunt for the Graf Spee. Four aircraft carriers, one battlecruiser, two battleships and sixteen cruisers spread a net across the southern Atlantic, hoping to catch and sink the German terror.

The Graf Spee was not easy to find. Over the next twelve weeks, the battleship steamed from the coast of Brazil to Madagascar, and back, sinking almost ten merchant ships along the way. She built a false funnel and turret, to disrupt her silhouette and confuse the enemy, and was always a few steps ahead of the hunters.

On December 7, The Graf Spee’s Captain obtained secret documents on the shipping routes for the area from the crew of the freighter Streonshalh, before sinking her. From the information, he decided to bring his ship to Montevideo, and attack the ships coming out of that port.

The Graf Spee’s Arado floatplane broke down around this time, and could not be repaired at sea, effectively blinding the ship past the horizon. The ship’s disguise was removed, to prevent it hindering her in a battle. Langsdorff knew he was going towards a hornet’s nest, but he had survived 30,000 nautical miles of open sailing and chase, and he trusted his ship and crew.

On December 12, 1939, the Graf Spee was approaching the mouth of the River Plate, and Montevideo. Unknown to Langsdorff, Commodore Henry Harwood knew there was a German ship in the area, likely headed to Montevideo. He moved the light cruisers, Ajax and Achilles and the heavy cruiser Exeter to the area, hoping to intercept his German adversary.

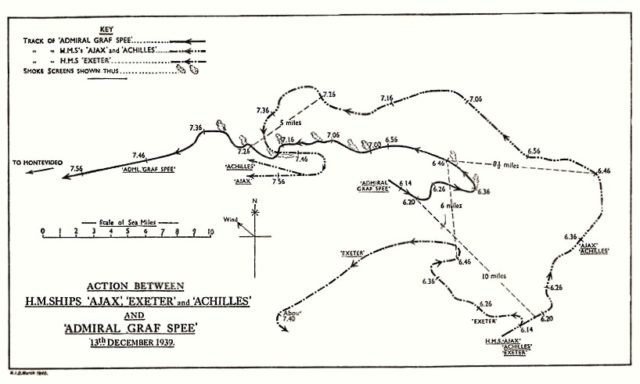

By 0520 the next morning, the Graf Spee was sighted by the British trio. The Germans had spotted the Exeter but mistook her for a convoy escort, and the two smaller ships as freighters. Realizing his mistake, Langsdorff ordered his ship’s diesel engines to increase to full speed. His 16,000-ton ship pushed forward, reaching a speed of 24 knots. At 0618 the Graf Spee’s forward 280mm cannons opened fire, sending shells hurtling towards the Exeter, while she pulled away from the other two cruisers. Within the next six minutes, all four ships had opened fire. At 0623, a shell burst near Exeter, effectively wiping out onboard communications and her torpedo crew. For the rest of the battle, everything onboard, including steering, was done manually.

Meanwhile, the Ajax and Achilles were trying to get ahead of the Graf Spee, to split her fire. The Graf Spee was firing at all three, sending 280mm shells at the Exeter, one after the other. By 0638, the Exeter was listing heavily, with only one turret operational and fires lapping at the side of her hull. Instead of retreating, she charged forward, at full speed, with a seven-degree list, and continued firing from the undamaged turret. She managed one decisive hit, to Graf Spee’s fuel processing plant and then she pulled away.

Seeing the Exeter pull away, the Achilles and Ajax pressed their attack. Knowing he had only 16 hours of fuel left, Langsdorff maneuvered the Graf Spee away, under a smoke screen. He headed southwest, with the two British cruisers shadowing him just 15 miles behind. Over the next 14 hours, the three ships played cat and mouse.

The Graf Spee reached the only neutral port nearby, Montevideo. Meanwhile, the British fleet assembled just outside the River Plate, waiting for the Germans to make a run for it.

Langsdorff was faced with a difficult decision. Risk the lives of his crew in a daring escape once repairs were made, or scuttle his ship and save the crew. Two articles from the Hague Convention had contradicting rules on the matter. Article 14 stated any belligerent ship could only stay in port for 24 hours, but Article 16 dictated they were not allowed to leave within 24 hours of an enemy merchant ship leaving. While the British and French publicly demanded the Graf Spee leave immediately, their merchant vessels left Montevideo in 24-hour intervals, forcing the Graf Spee to stay put.

Langsdorff had political pressure urging him to make a fighting break out of Montevideo, and go down fighting with his ship. However, he was an old-fashioned Kapitan and valued his crew over the propaganda needs of Germany’s new government. He decided to scuttle his ship, likely saving hundreds of his men. On December 17, 1939, KMS Admiral Graf Spee, once the greatest threat to Allied shipping in the South Atlantic, was burnt and sunk in Montevideo harbor. Langsdorff traveled to Argentina, before committing suicide, knowing he had failed, and would likely be put to death if he returned to Germany. He was buried with full military honors, in a funeral attended by some British officers.