In an audacious desert crossing, Laurence and his Bedouin group reached Aqaba and launched an attack against the bastion on the morning of July 4, 1917.

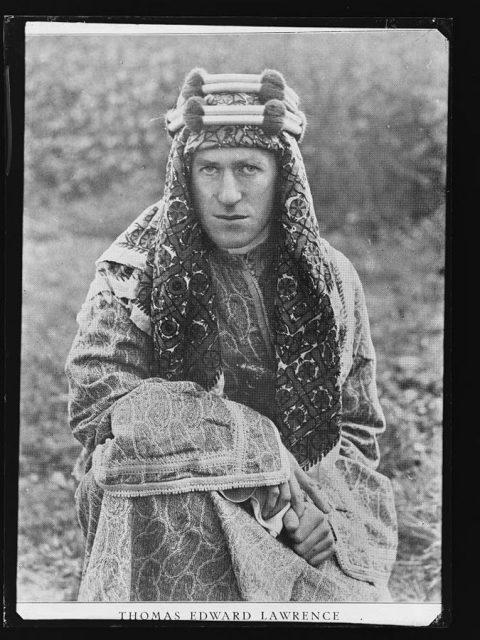

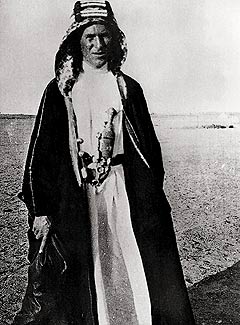

Lawrence of Arabia was a celebrated British archaeologist, writer, warrior, and spy. He led a Bedouin troop in open revolt against the crumbling Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

Thomas Edward Lawrence’s story has fascinated millions of people for decades. In 1919, an American journalist made a slide show detailing his exploits and presented it to a packed audience at Madison Square Garden in New York. He later toured England very successfully.

The tale of a British officer of the Empire fighting in the desert like a local Bedouin was so different from the classic image of a gentleman soldier fighting in the First World War that it really captured the public’s interest.

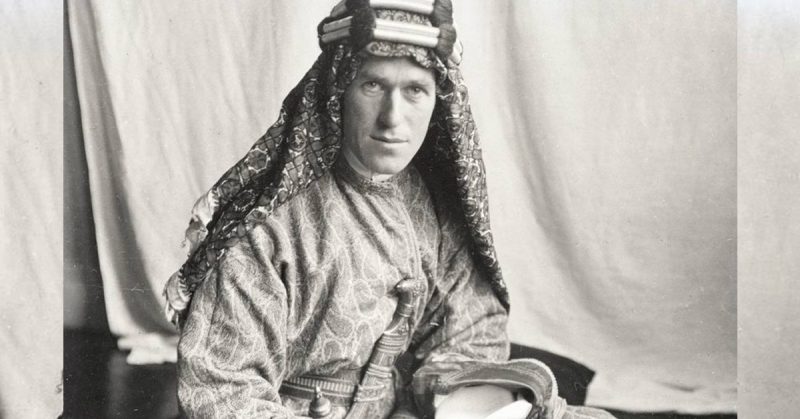

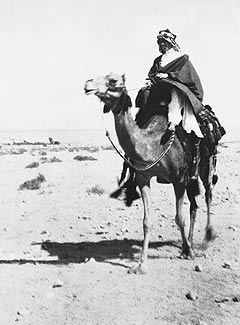

Instead of wearing the familiar British uniform, Lawrence sat up high on a camel, sporting a curved dagger, a broad headscarf wrapped around his head, and dressed in Bedouin attire. He resembled the romantic image of an Arab knight more than he resembled his British comrades who languished in the muddy trenches of Belgium and France.

Lawrence was in his twenties when he became the hero of an adventure saga.

He espoused the first modern theory of guerrilla warfare

As a student at Oxford, he had dreamed of giving new impetus to the Arab world, which he described as follows:

“A first difficulty of the Arab movement was to say who the Arabs were. Being a manufactured people, their name had been changing in a sense slowly year by year. Once it meant an Arabian. There was a country called Arabia, but this was nothing to the point.”

So he styled himself as a modern hero in the tradition of the Crusaders. As a young archaeologist in 1909, he had explored Crusader castles in the Holy Land and made them the subject of his thesis.

Moreover, Laurence knew Arabic, a language which he had perfected during archeological excavations in the Hittite Carchemish region in 1914. That was where he had met Gertrude Bell, a fellow British adventurer.

His research became a smokescreen to enable the military to conduct a cartographic expedition through the Negev Desert on behalf of the “Palestine Exploration Fund.” The maps created on that expedition later served as a strategic material for the British Secret Service.

Laurence’s success with small combat groups operating in the rough desert terrain is excellently portrayed in the 1960s British movie Laurence of Arabia.

Directed by David Lean and starring Peter O’Toole as Laurence, the cinematic depiction of his struggles in Greater Syria was nominated for ten Oscars. It won seven, including Best Picture and Best Director.

However, the real Lawrence was unable to realize his dream of a Greater Arab Kingdom under a single king. The British and French had a different idea for the region.

The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement concerning the division of the defunct Ottoman Empire between the two European powers was already in the making. To a great extent, the treaty is still the harbinger of many a flashpoint in the Syrian-Iraqi region to this day.

In Lawrence’s view, the British betrayed the Arabs

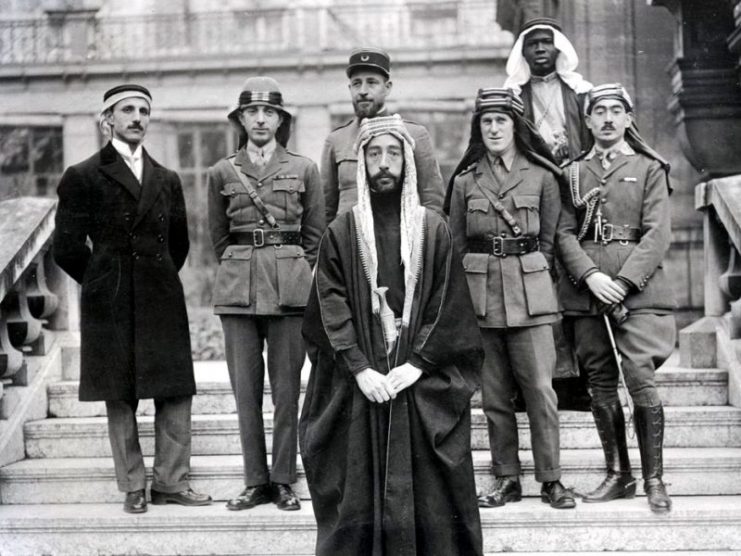

The British kept their plans a secret from Emir Faisal, the leader of the Arab revolt. Publicly, Lawrence could not do much. However, it is probable (although not proven) that he told Faisal everything the French and British had planned.

In any case, Lawrence and Faisal hatched a plan to move as quickly as possible to Syria, especially to Damascus, to offer Britain and France a fait accompli.

The duo set their sights on the Ottoman Fortress of Aqaba on the Mediterranean coast. They needed to get there before the British, who had already taken the Sinai Peninsula and were marching north along the Red Sea.

In an audacious desert crossing, Laurence and his Bedouin group reached Aqaba and launched an attack against the bastion on the morning of July 4, 1917. The soldiers in the garrison, although entrenched, handed over the city without a fight.

Since there was hardly any sustenance or gold for the men to be found in Aqaba, Lawrence immediately departed on a camel for Cairo. As soon as he brought word of the conquest to the British, they sent ships with food, weapons, and gold to Aqaba.

The war against the Ottomans continued with Laurence taking part in the fall of Damascus. He then was instrumental in establishing a provisional Arab government under Faisal –– Laurence envisioned the city as the capital of an Arab state. However, it was not until many years later that the Arabs would become the masters of their own destiny.

Lawrence, as a confidante of King Faisal, had far more influence over the diplomatic stage at post-war conferences than any other politician of the time. Many remember him fighting loyally next to the charismatic Arab leader for the Arab cause.

However, Laurence understated the extent of his secret service activities. He is said to have been a secret agent before the excavations in Carchemish, where he photographed the new Ottoman railway line. We will never be sure whether British interests were always at the forefront of his mind.

Later years

After the war, Lawrence went to work for the Foreign Office, but office work didn’t suit him. So, in August 1922, he tried to enlist in the Royal Air Force (RAF) under the false name of John Hume Ross. Flying Officer W.E. Johns interviewed him but turned him down, suspecting that the name of Ross was a false one.

A short while later, Lawrence returned with an RAF messenger who carried a letter saying that Johns had to admit Lawrence to the RAF.

Unfortunately, Lawrence’s spell in the RAF didn’t last for long. In February 1923, he was forced out when his real identity was exposed. He joined the Royal Tank Corps under a new false name, but missed the RAF and repeatedly applied to be readmitted. His request was granted in August 1925.

Two months after being released from the military in 1935, he came off the road while riding his Brough Superior SS 100 motorcycle. He was riding near his cottage in Clouds Hill, Dorset, and didn’t see two boys on bicycles due to a dip in the road. When he swerved to avoid them, he crashed into a tree.

Read another story from us: Mata Hari-The Naked Truth of The WW1 Spy

Lawrence remained in a coma until he passed away six days later on May 19, 1935. He was only 46 years old.

At his funeral, E. M. Forster, the British novelist, wept over the end of the man who had shaped his life in the image of an adventure in 1001 Nights.