Most of us have seen the iconic movie Schindler’s List, produced and directed by the famous filmmaker Steven Spielberg. Without a doubt the scenes, oftentimes brutal, left a mark on our minds and hearts.

Remember the little girl in the bright, crimson red coat in an otherwise black-and-white setting. She shines out like a beacon amid the carnage and brutality taking place all around her. The excellent camera work and the knowledge that Schindler’s List is a true story make this cinematic depiction all the more potent.

Oliwia Dąbrowska from Poland played the part of the girl in the red coat after she was cast for the role in 1993. She was three years old at the time. And when she met Steven Spielberg for the first time, she had to promise him that she would not watch the film until she turned 18.

But she broke her promise to Spielberg—a choice she came to regret. After hearing so much about her part in the movie from family and friends, she decided to take a sneak peek when she was 11 years old.

Too young for such horror

It was definitely too young to bear witness to the antics of the infamous SS-Hauptsturmführer Amon Göth, played by Ralph Fiennes. The English actor spent countless hours trying to understand Göth’s character before taking up the role. He even tried blotting out all thought to recreate the boyhood feeling of shooting down cans on a wall with an air rifle.

Immediately, a signature scene comes to mind. We remember a man sporting an undershirt and his uniform breeches, relishing his birds-eye view from the balcony of his villa. However, this is no ordinary vista of a quaint, idyllic backdrop or a calm ocean. Instead, the vast Kraków-Plaszów concentration camp is spread out before him.

He then takes a deep drag from the cigarette hanging from his lips. On his shoulder his rifle is loosely perched, reflecting his complete nonchalance. But his eyes, fierce and twinkling, displaying almost maniacal glee, are directed downwards.

Then, he pulls one more time on the cigarette before setting it down to his right. The man calmly leans forward, takes aim, and starts randomly shooting. This capricious act of violence targets innocent men, women, and children who just happen to catch his attention.

So it comes as no surprise that Oliwia was left traumatized by the experience of watching the movie. She even felt ashamed for her part in it, asking her parents to stop telling other people that she had ever acted in the film.

Only when she turned 18 did Oliwia risk seeing the movie a second time. It was only then that she understood the pivotal role she played in making Schindler’s List one of the most successful cinematic productions of all time. Now, she is able to say she is proud of her part in it.

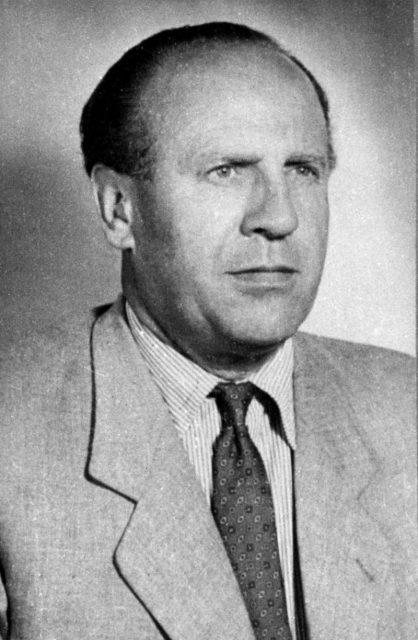

Oskar Schindler

The film portrays the story of Oskar Schindler, the man who saved more than 1,000 Jews from deportation to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. He was an unlikely candidate for such a role, to say the least. The movie correctly depicts him in the opening scenes as an opportunistic businessman who sees the war as his best chance to gain riches.

And he does so with a flamboyant and cunning flourish. With the help of the smart Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern, played by Ben Kingsley, Schindler sets up the Deutsche Emailwarenfabrik Oskar Schindler (“German Enamelware Factory Oskar Schindler”). The riches soon come pouring in, seemingly setting him up for life after the war.

However, he soon realizes the brutality of the Nazi regime. Stern, acting as his conscience, slowly but surely eats away at Schindler’s insouciance with shrewd ploys. However, it is the little girl in the red coat that really shakes Schindler’s morality to the core.

The girl in the red coat

From his vantage point on horseback on an outcrop overlooking Kraków, Oskar Schindler witnesses the March 13, 1943, liquidation of the Krakow ghetto. Spielberg devotes 20 minutes of the movie to this bloodbath. It is a brutal and yet masterful depiction of one of humanity’s most shameful moments.

Wherever something happens, the camera is at eye level amid the victims—on the stairs of the houses, in the filth of the backyards, on the roadside where the corpses are piled up, in the storeroom which is riddled with bullets. The result is a rhythmic mosaic of murder which is no longer an illustration of events, but rather a portrayal of pure panic, throbbing horror, and a rampage of fear oozing onto the screen.

The aesthetics of the old newsreel do not return here. Instead, the effect of television reporting—the snapshot reality of street scenes that could have taken place in locations such as modern-day Syria—are reflected into a past when there was no television. With these chilling images, which are without equivalent in film history, Spielberg manages to fuse documentary-style filming with cinematic drama.

From this point on, the film traces all the phases of one of the most extensive exterminations known to history. The viewer is taken on a voyage from the cattle carriages, to the macabre selection process, to the so-called “disinfection” at Auschwitz, finally breaking the myth that overshadowed this hell.

Something awakens in Schindler when he sees the frightened little girl in a crimson-colored coat, weaving her way through the carnage until she finally disappears into a doorway, seemingly safe. A year later, he again encounters the girl in the striking red coat—on a cart containing ghetto victims as it jolts over the rough ground toward a pit where the corpses are laid to rest in flames.

It is sometime between these two pivotal moments in the movie that Oskar Schindler decides to play his part in the thwarting of the Final Solution.

With the help of Stern, he compiles a list that would be remembered by generations of Jews to this day. It is an act of compassion and bravery that gains in momentum until the end of the film.

It shows how a onetime unscrupulous businessman spends his entire ill-gotten fortune to save the lives of 1,100 men, women and children from the slaughter of Auschwitz.