For all of us at War History Online this it is a real honor to share this story with you. For us, it started when we were in Normandy earlier this year and happened across a plaque on an old barn wall. It was rather an emotional moment as it was just so unexpected.

It wasn’t a grand marble memorial – it was a simple and powerful salute to the crew of a C-47 and to all the paratroopers on board. Through a mutual friend – Paul E Clifford – we are able to publish the full story behind this crash site plaque and another crash site plaque. It starts like this…

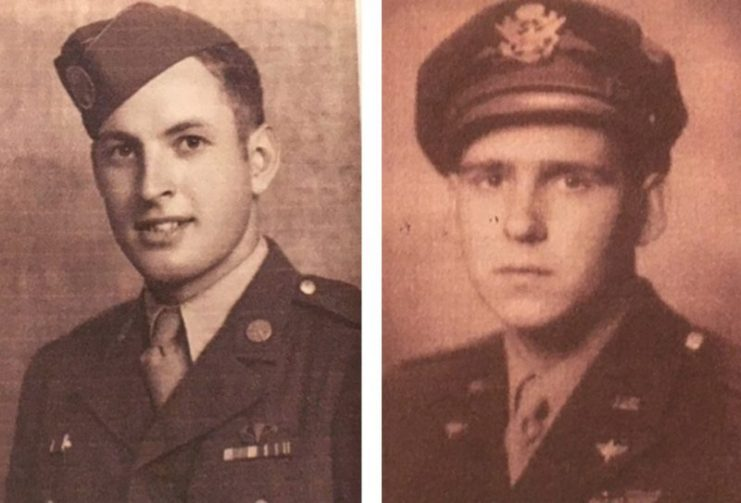

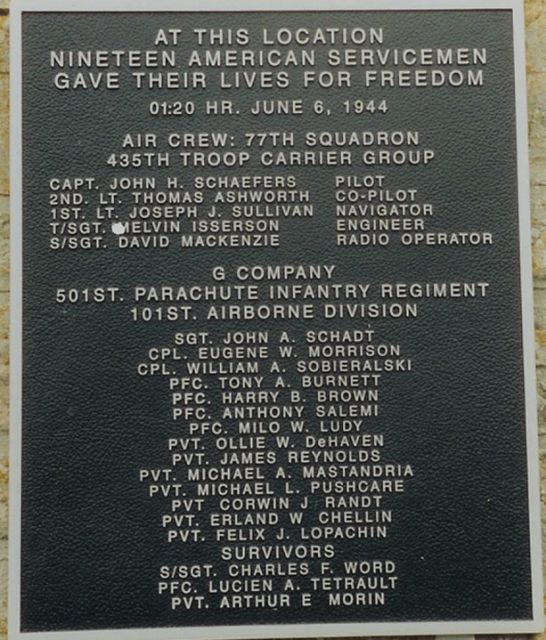

Lieutenant Joseph Sullivan was one of the first Americans to give his life for his country on D-Day morning, June 6, 1944, in Normandy, France. The C-47 troop carrier transport that he was navigating, tail number 42-33047, from the 77th Squadron of the 435th Troop Carrier Group, was hit by German anti-aircraft fire and crashed near the hamlet of Clainville at 1:20 a.m.

Of the twenty-two men who boarded the airplane in England, only three survived, all paratroopers assigned to G Company, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division.

The five aircrew on the airplane were among those killed. In the months that followed, all of those who perished in the crash were identified, with the exception of Joe Sullivan. Joe’s mother, Katherine Sullivan, was in contact with all of the families of the other aircrew and learned how each family had been notified that their loved one’s remains had been identified. Joe’s family did not learn the circumstances of his death, or how his remains were eventually identified, until 1982! This is Joe Sullivan’s story – from June 6, 1944, until June 6, 2018.

When WWII ended in August of 1945, Joe Sullivan remained the only Missing in Action (MIA) casualty from the crew and paratroopers on board the C-47 that now sat as burned wreckage in a Normandy farmyard. In 1946 Joe was officially declared as KIA and his mother received his death benefits. There was, however, no further information regarding his remains.

Then, in January, 1948, Katherine was notified that her son’s remains were located in a temporary grave in Belgium, and that the Memorial Affairs Office of the War Department wished to know if she wanted her son buried in Europe or returned to the United States for interment. The Sullivan family was shocked! Belgium!! Why was he there? What had happened between 1944 and 1948?

Inquiries were made to several members of Congress and to the War Department. No answers were forthcoming. Finally Katherine asked that her son’s remains be returned to the United States and that he should be interred at Cypress Hills National Cemetery, near the family home in Woodhaven, Queens, in New York City.

I had grown up hearing the story of the tragic loss and mystery surrounding the death of my mother’s brother on D-Day. I also had a love of history, earning my degree in the subject and spending a great deal of time reading military history, particularly WWII military history.

After college and a tour in the U.S. Army I began a career with the Federal government and was rewarded, in November of 1980, with a promotion that required a move to Washington, DC.

Shortly after my arrival in the nation’s capital, I took the last letter that my Uncle Joe had written to my mother, two days before his death, and visited the National Archives, using Joe’s return address on the letter to ask the staff how I might find details regarding my uncle’s death in Normandy.

Utilizing the advice I received, I was soon in possession of the official Missing Aircrew Report regarding his aircraft, along with statements made by three surviving paratroopers. I was also directed to the DoD Memorial Affairs Division in nearby Alexandria, Virginia. What I discovered in the Memorial Affairs files left me both exhilarated and deeply saddened.

Joe’s Memorial Affairs file was several inches thick, and contained an amazingly complete chain of communications between various government agencies and elected officials, including the many original letters from my grandmother to each of these organizations and officials.

The top piece of paper in the file is the one that broke my heart. The faded typed words were on official Department of the Army letterhead and addressed to my grandmother.

The nearly unreadable original letter was dated March 10, 1948, and stated that the wreckage of Joe’s airplane had been searched by a U.S. Army mortuary team on July 18, 1947, resulting in the identification of Lt. Sullivan’s remains. The letter listed the identifying evidence as: (1) his dog tags; (2) a set of USAAF navigator wings inscribed with his military serial number; and (3) a silver identification bracelet inscribed with his name, and serial number.

The letter also stated that his remains had been moved to a temporary grave at a U.S. military cemetery in Belgium.

The original, unsigned, letter was paper clipped to several carbon copies. I stared at the letter for a long while, realizing the obvious: The original unsigned letter I was holding had been placed in Joe’s Memorial Affairs file having never been signed and mailed to my grandmother! Because of an administrative error this letter explaining what had happened to my uncle, along with the carbon copies, had been in this folder for almost forty years……….. and my grandmother had never learned the story of what happened to her son!

After the heartbreaking discovery that solved the family mystery, I thought that my involvement with “The Story of Uncle Joe” was over. It wasn’t. Several months after my visit to the Memorial Affairs office I was reading the New York Times Sunday Book Review and saw an Author’s Inquiry from a man by the name of Milton Dank.

Dr. Dank was looking for fellow WWII Troop Carrier Command veterans for a book he was writing. I had given some thought to trying to find men who had served with my uncle, both to learn more about his life in the military and to inform them of the results of my research. I wrote to Milton Dank and he was able to provide me with several names and addresses of men from my uncle’s Squadron.

One of the names and addresses was a man named Joe Flynn – this information would have immense impact on me over the next few years as, unknown to me, Joe Flynn had been my uncle’s closest friend in the 77th Squadron.

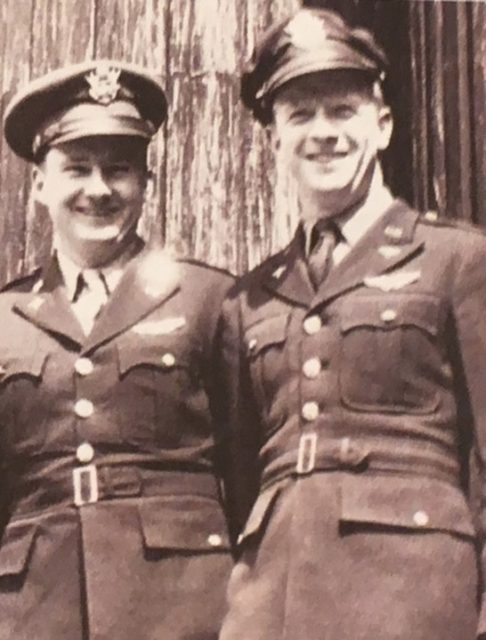

After receiving my letter Joe called me from California and a new friendship began, between a WWII veteran and the nephew of that veteran’s best friend from WWII. Joe filled me in on the history of his friendship with my uncle and the history of their unit, of which both men had been founding members. During our conversations I learned that Joe had been navigating for a three airplane element on D-Day and that a second C-47 in Joe’s element had been shot down immediately prior to the loss of Joe’s aircraft.

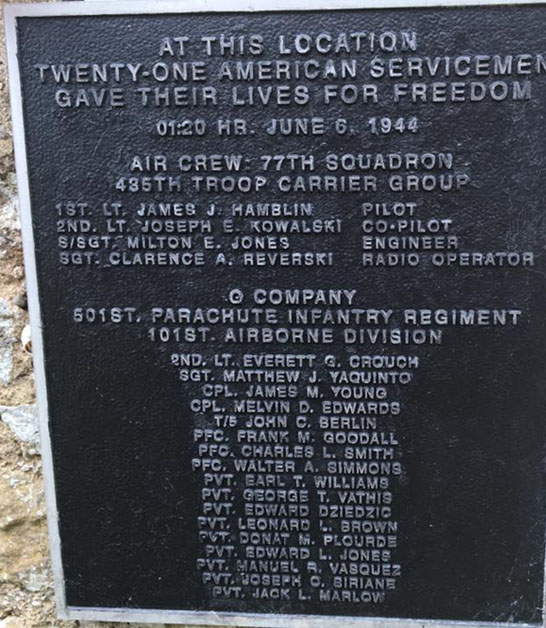

Joe Flynn also put me in touch with Colonel Phillip “Pappy” Rawlings who had been the 77th Squadron Operations Officer on D-Day. Colonel Rawlins had written a history of the 77th entitled, “Red Light, Green Light, Geronimo!” that he forwarded to me. The superb history, written shortly after WWII, clearly indicated how little the 77th Squadron veterans had learned about the loss of Joe and his crew, as well as the second C-47 from their element that had crashed just several miles from Clainville, near the village of Founecrop.

My next adventure with the story of learning about my uncle occurred when I received an invitation to the 1998 reunion of the 435th Troop Carrier Group in San Antonio, Texas. The reunion was a very emotional experience for me.

After I addressed the veterans and their families about my research I was immediately accepted by the group as one of their own because of my family connection. One of my uncle’s good friends from the 77th, another navigator, told me of his memory when Joe arrived in the 435th Officers Club one night in early 1944 and bought several rounds of drinks to celebrate the birth of his new nephew – me!

Once again, I thought that I had reached the end of the story about my uncle Joe. Once again I was wrong.

One of the 77th Squadron pilots at the San Antonio reunion , Jesse Harrison, had shared a very unique and amazing story with me. He told me that he was badly burned when his C-47 was shot down in Holland in September of 1944. During his hospital stay in England he was visited by another wounded soldier, Jack Urbank.

Jack was one of the paratroopers from G/501 who had jumped from Jesse’s C-47 in Normandy. The 77th pilot and the paratrooper spent many hours talking in the hospital as they were recovering from their wounds. A sincere friendship grew between the two men and they remained in touch over the years.

After returning from the 1998 reunion in San Antonio, Jesse called Jack and told him about my research into the loss of the two 77th C-47s on D-Day. Jack was intrigued about what I might know about the paratroopers on those airplanes, many of whom had been his friends.

Jack, in turn, told the story of my research at a 501st reunion the following year. Several of Jack’s friends from G/501 took an interest in what I had learned and two G Company veterans, Don Kane and Ray Geddes, contacted me, initiating yet another chapter of D-Day history into my life, as both men lived near my Alexandria, Virginia, home. I visited with Don and Ray, explaining events as I had discovered them, and learning from them as first person historians.

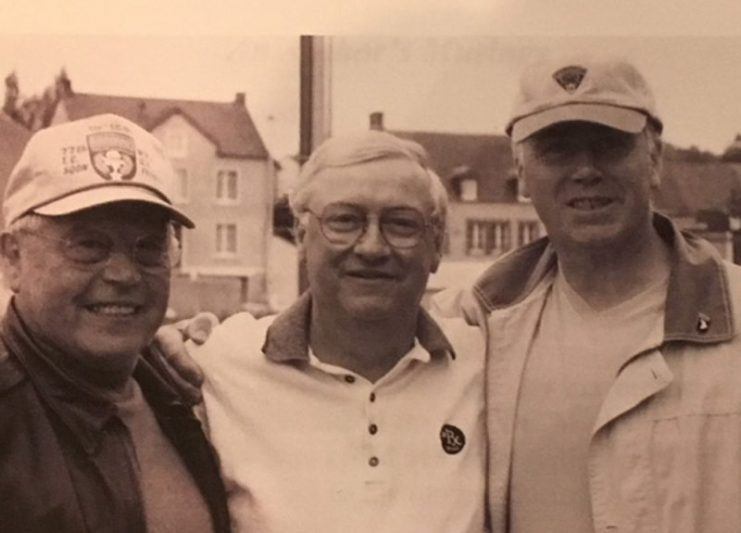

By 1999 I knew not to say that meeting the 501st veterans was the “final” chapter in my D-Day historical adventure. I was correct. After a great many telephone conversations and mailing of letters – e-mail was new, and not a tool employed by these gentlemen – a very unusual and history-making reunion was arranged that included 77th Squadron Troop Carrier pilot Jesse Harrison and several of the paratrooper veterans of G/501, including Jack Urbank, Don Kane, Ray Geddes and several other G/501 vets – ALL of whom had jumped from Jesse’s C-47 on D-Day morning.

The reunion was arranged by Ray Geddes and took place in July of 2000, near his home in Baltimore, Maryland. To this day we believe that this meeting was the only formally organized meeting of a D-Day troop carrier pilot with men who had jumped from his airplane on that mission.

The Maryland reunion was a wonderful occasion, as the veterans and their wives, along with my wife Denise and I, engaged in many interesting conversations. The most significant conversation, that eventually involved everyone in the room, was the idea that plaques would be made to honor the young Americans who had died on the two airplanes that had flown in three plane formation with Jesse Harrison on D-Day morning.

Jesse volunteered to arrange for both the production and costs of the plaques. It would be my job to get them placed at the crash sites in the Normandy villages of Clainville and Founecrop!

The details of implementing our plan were complicated, to say the least! I was coordinating details in the U.S. while arrangements in Normandy were being handled by Philippe Nekrossoff, a French national policeman, ex-French Army paratrooper, and aspiring D-Day historian. Once again, Joe Flynn was involved. Philippe and Joe had become friends during Joe’s attendance at the D-Day 50th Anniversary in 1994. Joe, in turn, had connected Philippe and I because of our interest in D-Day events.

As we set the final schedule to place the plaques we also learned who would be on the list of attendees for the occasion. Joe Sullivan’s family would have my wife Denise and I, along with two cousins, Katherine Smith and Marge Young, and their spouses.

The paratrooper families would be represented by Art Morin and his wife, Patti. Art, the son of one of the three G/501 survivors, had volunteered to take on the arduous chore of transporting the plaques to Normandy. The 77th Squadron would be represented by Bud Busiere and his wife Louise, whom I had met at the San Antonio reunion.

Bud, a flight engineer in the 77th, sat with me at the reunion and in a very private conversation as he described watching my uncle’s plane and the other 77th Squadron C-47 as they took their final dives into the Normandy countryside. Bud would be the only D-Day veteran to make the trip with our group.

Our group met in Paris on September 4th, 2001, and had a wonderful dinner together where everyone got to know each other. In the morning we left for Normandy on an early train and were met by Philippe and Michal Gaudry. Philippe would be in charge of logistics and our schedule during our stay, and Michel would be challenged by the difficult translation chores.

We spent the remainder of September 5th touring St. Mere Eglise with Philippe and Michel as our tour guides. On the morning of September 6th we set out in a van that Philippe had rented and proceeded to Clainville – where my cousins and I viewed for the first time the farmer’s field where our Uncle Joe and 18 other American warriors had died.

While we were gathering next to the field we were met by the then owner of the farm, Claude Dulenay, and two other local residents, Regis and Patricia Bissett, the owners of the location where we would be making our next stop, the second 77th Squadron crash site in Founecrop. More introductions were forthcoming, with Philippe as the Master of Ceremonies.

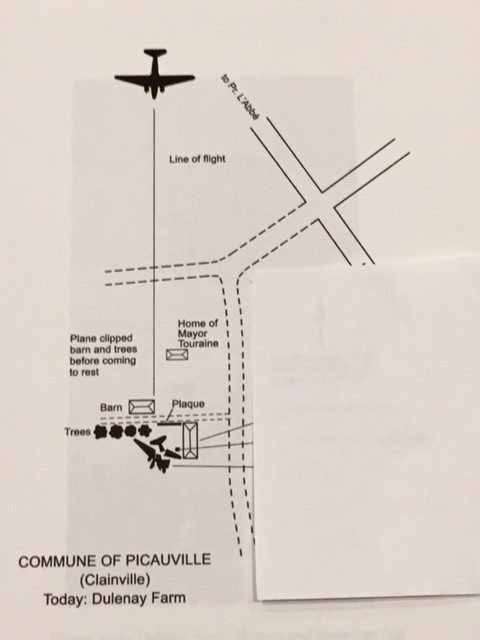

The most important part of our initial arrival at the site was Philippe’s description to us of the direction from which the C-47 had come out of the sky that early morning on D-Day, and the damage that was done to the farm’s barn and the trees along the roadway. After the eerie feeling of processing the events that Philippe described we were all – especially the Sullivan family descendants – silent with our thoughts.

Ken Smith, my cousin Katherine’s husband, brought us back to reality as he returned to the van and asked for help in carrying the plaque and the tools for mounting it from the van to the stone wall where the plaque would be mounted.

Ken and Regis, despite the fact that they could not speak a word of the other’s native language, worked well together and got the plaque mounted on the location on the wall that the group had voted as most appropriate. Ken – God bless him – handed me a wrench and let me do the final tightening on the four bolts that would secure the plaque.

When the plaque was finally attached to the wall we all stepped back to view the new addition to this historic site. Everyone was both surprised and touched as Philippe returned from his car with a bouquet of flowers and an American flag, which he against the wall beneath the plaque.

Now it was time to address the reason for our being in Normandy with this wonderful group of people. I spoke on behalf of my Uncle Joe and my grandmother about the roles that so many people, including Jesse Harrison, Ray Geddes, Joe Flynn and Philippe had played in what we had just accomplished. My cousin Katherine delivered additional sincere words on behalf of our grandmother.

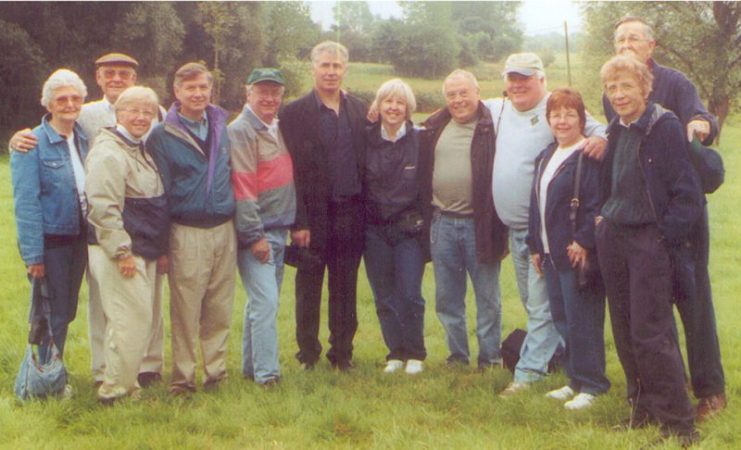

Bud Busiere spoke for the men from the 77th Squadron and Art Morin gave thanks that his dad had been one of the G/501 survivors while so many others had died. There was a pause after Art finished, and I can’t remember who came up with the idea, but it was decided that we would walk into the middle of the field, where Regis took a picture of all of the visitors from the United States who were finally smiling after the informal but emotional event for which we had so long prepared.

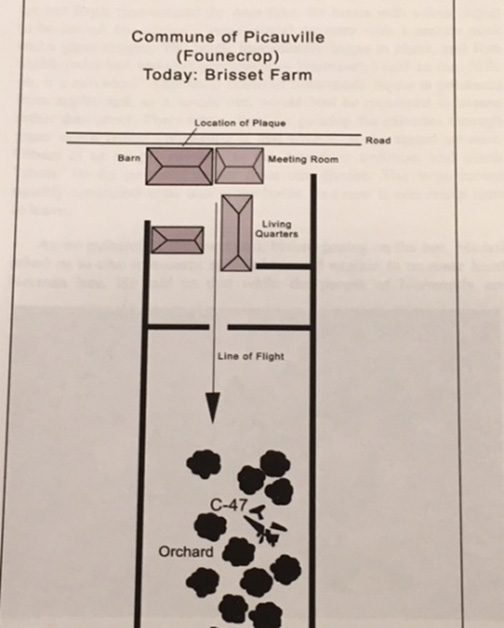

After the picture was taken, and we had returned to a lighter mood, we boarded our van and followed Regis and Patricia to their nearby home in the hamlet of Founecrop. We were very surprised to find a group of 15-20 local residents waiting for us when we arrived.

Many of these new friends were very excited to meet us as they had been young children who had been living in Founecrop on D-Day. Michel and Philippe had quite a challenge on their hands as they tried to interpret both the description of events by the witnesses to history and the questions from descendants of the men who had made the history.

While all the historic discussion was going on Ken and Regis continued their new role as plaque installers. Once again, when the plaque was anchored to the stone wall we gathered to speak of the importance of the occasion. In this case the ceremony took longer because Michel would interpret all of what we said for the French audience.

In addition, both Ray Geddes and Don Kane had asked that comments be read in their names. Don’s words were particularly poignant as he had been removed from the Founecrop airplane at the very last minute by an officer who wanted to change planes, thus saving Don’s life.

As soon as our comments, and the translations, were completed, Regis called for everyone’s attention and said that all were invited inside his and Patricia’s home for a celebration. We were both surprised, and grateful. It was a wonderful party, and it seemed that as the wine glasses were re-filled several times the need for Michel or Philippe to interpret was less necessary. The several hours that followed were an event that everyone present would long remember.

We departed Founecrop in mid-afternoon amid much cheering and kissing between the American and French groups. A calm evening in our hotel and early bedtime ended a once-in-a-lifetime experience. The next day we departed for various locations as the American contingent spread out for individual tourist spots throughout Europe. Eventually we were all entangled in 9/11 events that kept us in Europe for an extended period. But that’s another story.

This diagram of the Clainville crash site is based upon the original sketch of the location by Lt. John Hoover, who supervised the search of the wreckage in 1947, when Joe Sullivan’s remains were identified. The line of flight arrow is pointing east, and the plaque location is indicated on the wall separating the road from the field in which the wreckage was located.

The entire story of the two 77th Troop Carrier Squadron aircraft lost on D-Day is available on Amazon, or with a signature and inscription from the author at: smallhistory@aol.com

All photos provided by the author.