What the American troops quickly discovered was that they had walked into a trap

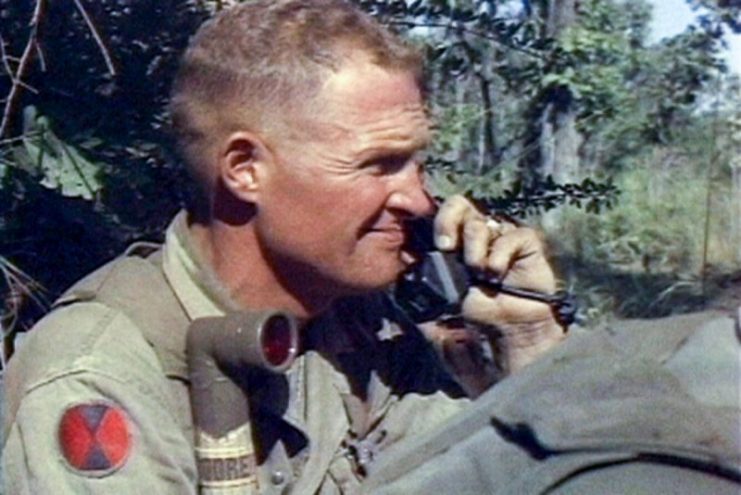

“Hate war, love the American soldier,” was a mantra that legendary Lieutenant General Hal Moore not only believed, but also lived by. While Moore hated war itself, he loved every soldier who served with him as a brother.

When he found himself and his troops outnumbered almost twelve to one at Ia Drang – the first major battle between American and North Vietnamese forces of the Vietnam War – he led from the front, and devoted every ounce of strength and determination he possessed to getting every one of his soldiers out of there alive.

His position at Ia Trang in November 1965 has been likened by many military historians to General Custer’s at Little Bighorn in 1876 – and many of the soldiers who served under Moore nicknamed him “Yellow Hair,” which was Custer’s nickname, seeing as both men commanded the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Unlike that ill-fated 19th century cavalryman, Moore succeeded, against all odds, in getting most of his troops out of a battle that seemed certain to end up as a massacre.

Moore’s story began on February 13, 1922, when he was born in Bardstown, Kentucky into a modest household. He left Bardstown at the age of seventeen without having graduated from high school, and moved to Washington D.C., where he got a job working in the US Senate book warehouse.

He worked days and studied at night, and in this way managed to complete his high school education. After this he continued to work at the warehouse while studying university courses at night. After a long wait and much effort, he managed to get a West Point appointment in 1942. He graduated with a commission as a second lieutenant in June 1945, as World War II was starting to come to a close.

He qualified as an airborne jumpmaster after WWII, and in the Korean War he commanded a heavy mortar company as a captain. After the war he returned to the US to work as an infantry tactics instructor, and also had a stint as a NATO Plans Officer in Norway. By 1964 he had earned a master’s degree and been promoted to lieutenant colonel, and in 1965 the battalion he commanded was redesignated as the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry.

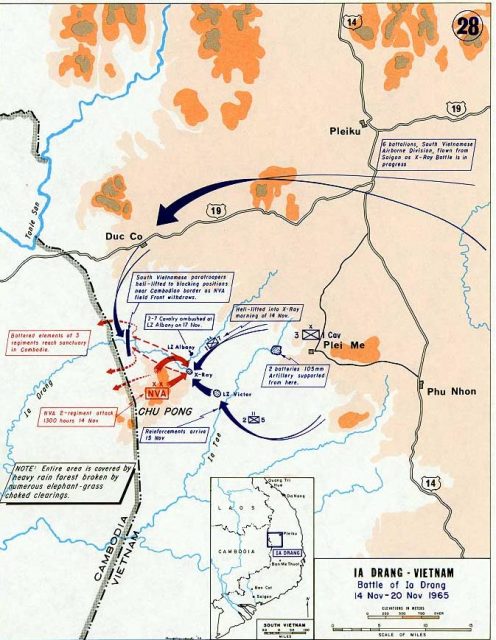

He was deployed to Vietnam in August 1965. On November 14, the 1st Battalion would land via helicopter at Landing Zone X-Ray in the Ia Drang Valley of South Vietnam, near the Cambodian border. What the American troops quickly discovered was that they had walked into a trap, and were soon almost completely surrounded by a vastly numerically superior NVA force, with no way out.

Rather than despair, Moore chose determination. He made a declaration: “I’ll always be the first person on the battlefield, my boots will be the first boots on it, and I’ll be the last person off. I’ll never leave a body.” He lived by this at Ia Drang, personally leading his troops into combat from the front.

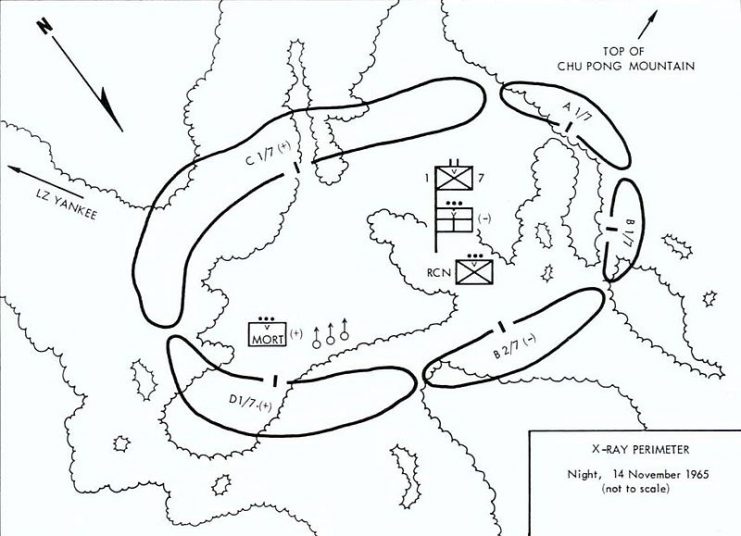

The fighting was immediately ferocious. Before the full complement of the battalion’s 450-odd troops had even landed, the 33rd and 66th regiments of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) launched multiple assaults against the American troops who were already on the ground.

Moore was caught in the thick of the fighting, and through his leadership and tactics he managed to keep American casualties to a minimum – although, under these circumstances, “minimum” was a relative term.

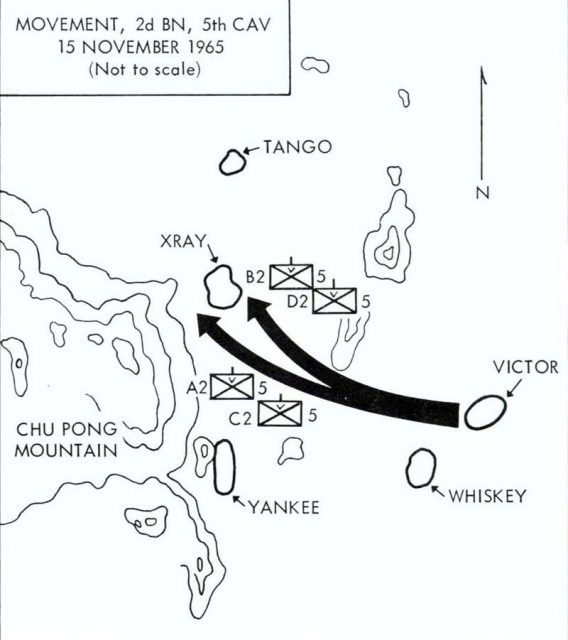

Intense fighting continued throughout the whole day. By the time evening fell, 87 American troops lay dead or wounded on the field, while around 200 PAVN troops were casualties. Thanks to the insertion of another American battalion, and the heroic efforts of a helicopter pilot who resupplied the troops on the ground under heavy fire, the American troops managed to hold their position without being overrun.

Moore and his men didn’t have much of a chance to rest. The next wave of PAVN attacks came just after seven the next morning. Rockets and mortars struck home deep inside the American perimeter, and hundreds of PAVN infantry troops attacked from a number of different directions.

Moore desperately directed machine gun and rifle fire on multiple fronts to try to stem the seemingly unstoppable waves of assaults against his steadily-weakening position. PAVN troops managed to break through the American perimeter in one section, and the combat there became fierce hand-to-hand fighting, with the PAVN troops eventually being repelled after heavy American losses.

Things were looking grim for Moore and his troops. There was no place for enough choppers to land to evacuate all of them from the situation, and it seemed certain that they would be overrun and massacred by the next day.

That night Moore and other officers prepared defenses for what they knew would be a furious assault aimed at completely overrunning their position. They were right: PAVN troops attacked in frenzied waves from 4 AM, pushing the defenders to their limits.

Moore had thrice been offered evacuation from the battle to meet with generals in Saigon, but thrice he had refused. He had said he was going to be the last to leave this battlefield, and he was determined to live by this.

Thankfully for the Americans, support for their beleaguered position came in the form of helicopter gunships and fighter-bombers raining down fire on PAVN positions, which caused them to retreat and allowed the American troops to finally be airlifted out. Over the three days of intense fighting at Landing Zone X-Ray, the PAVN had suffered around 2,000 casualties, with around 600 dead. American losses were 79 dead and 121 wounded.

Moore was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his valor at Ia Drang, and was later promoted to colonel. He retired from the military as a lieutenant general in 1977.

He visited the battlefield at Ia Drang many years later in the 1990s, where, in the spirit of reconciliation, he took the surprising step of meeting the North Vietnamese generals who had fought against him and his men.

He ended up writing a number of books, the most famous of which, We Were Soldiers Once…And Young, was adapted into the film We Were Soldiers. Moore also wrote We Are Still Soldiers. He lived to the ripe old age of 94, and passed away in his home in Alabama in 2017.