At the end of the nineteenth century, pistol designers were looking at ways to improve on the revolver which was at that time the standard military sidearm.

What was wanted was something that could be shot and reloaded more quickly than a revolver, but which still fired a large caliber round.

The first viable design for one of these “self-loading pistols“ (they wouldn’t be called “semi-automatics“ until later) came into production in 1896. However, the Mauser C-96 used a design similar to a rifle bolt, making it a bulky and unwieldy pistol.

In Germany and America, designers were working in parallel on new designs for more compact self-loading pistols, but what they produced were two very different handguns.

The Luger

In Germany, Austrian designer Georg Luger was working for the German arms manufacturer, Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken (DWM), when he produced a design for an improved version of the existing Borchardt C/93 pistol.

It was an innovative design, though ultimately not reliable enough to be practical as a military sidearm.

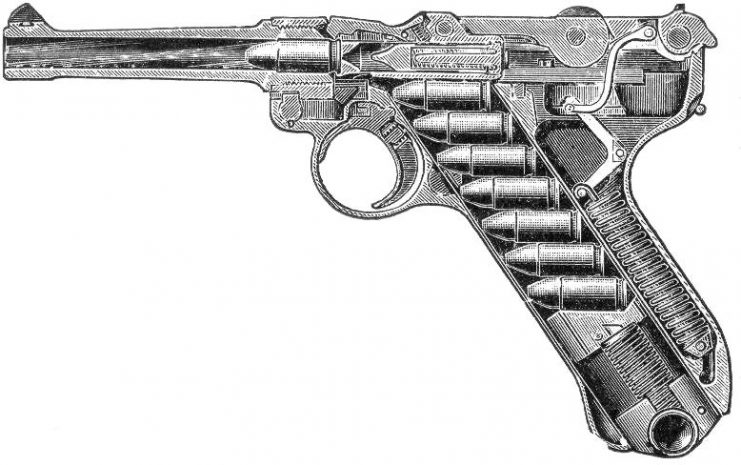

His design was for a recoil-operated pistol which used an internal striker rather than a hammer and employed a novel toggle mechanism.

Blowback caused the barrel and toggle to move backward until hitting a cam, which hinged a toggle joint, extracting the spent cartridge. A spring then forced the toggle closed, pushing the next round into the breech.

The result was a handy-sized pistol which held up to seven 7.65mm Parabellum rounds in a drop-out magazine. DWM began manufacture in 1900 after the Swiss Army became the first to adopt the new design.

In 1904, this pistol was upgraded to take the new 9x19mm round (which is now known universally as the “9mm Luger”), and in 1908 it was adopted as the main sidearm of some units of the German army. At that point, it received its formal designation: the “Pistole Parabellum 1908” or “P.08.”

However, it quickly and universally became known as the “Luger“ and, for the sake of simplicity, that’s how I’ll refer to it here.

A Luger in good condition is a beautiful piece of engineering. The toggle mechanism works smoothly and the whole pistol has a feeling of durable quality. That’s not surprising because the manufacturing process was complex and lengthy.

Back in the early days of the twentieth century, there weren’t precision CAD-CAM machines to produce parts with surgical accuracy, so each part of every Luger was machined by hand. The resulting tiny variations in dimension and finish meant that highly skilled inspectors assembled each finished pistol.

They would take baskets of Luger parts and sort through them until they found a set that worked perfectly together, finishing each piece by hand to ensure smooth and reliable operation.

This was a laborious process and, when it was finished, each part of the pistol would be stamped with a serial number. Then, the pistol was disassembled, and the parts sent for bluing and hardening.

After this was complete, the pistol would be reassembled using the serial numbers to ensure that the right parts went together. That’s why a genuine Luger has serial numbers stamped on virtually every component, and it means that each gun is a hand-finished piece of German precision engineering.

It wasn’t perfect. The mechanism that linked the trigger to the internal striker was long and complex. The trigger itself was horrible, being mushy and imprecise despite being light. The rear sight was mounted on part of the toggle so, when fired, the rising toggle momentarily obscured the view of the target.

Generally, however, the Luger worked well and the toggle mechanism absorbed a fair amount of the recoil, making it easy to keep on target.

The barrel on the Luger was a removable part and this pistol was produced in three different barrel lengths: 4″, 6″, and 8″ (Artillery). The Artillery version featured adjustable rear sights, a removable wooden stock to turn the pistol into a carbine, and an optional 50-round drum magazine.

By the outbreak of World War One, the Luger was in widespread use in the army and navy of Germany.

The Colt 1911

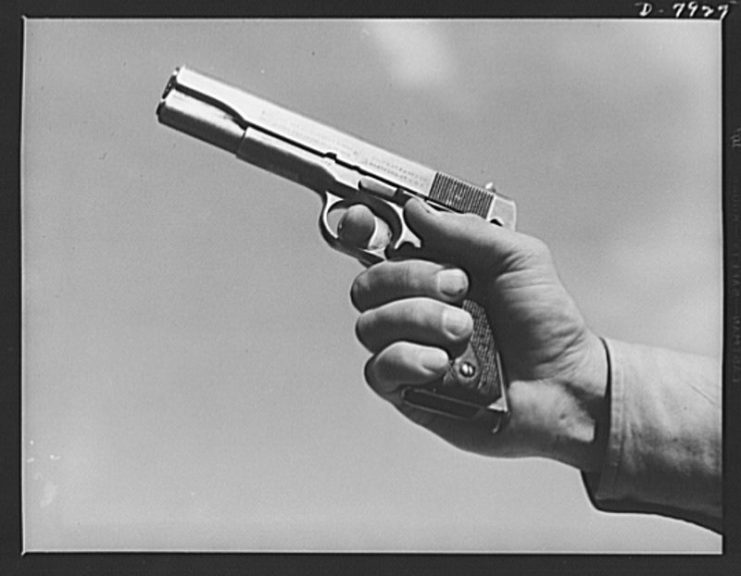

In America, firearms designer John Moses Browning had also been working on a design for a self-loading pistol, though he took a very different approach.

His first design was completed in 1897 and it featured not a toggle like the Luger, but a moving slide which was propelled to the rear by venting gases and then extracted the spent cartridge. A set of springs then pushed the slide forward to chamber the next round in the breech.

This design might have lacked the precision of the German pistol, but it proved to be reliable and easy to manufacture.

The first commercially produced Browning-designed semi-automatic wasn’t manufactured in America though. Americans still seemed to be wary of the new-fangled self-loading pistols and were content to stick with revolvers.

However, the Belgian Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre (FN) purchased Browning’s design and began production of the FN Pistolet Browning in 1899.

This .32” ACP caliber pistol proved to be extremely reliable. In tests, it was found to be capable of firing more than 500 rounds without a jam or misfire. A modified version became the standard sidearm of the Belgian army in 1900.

Browning went on to produce a series of self-loading pistols both for FN and for Colt. However, the US Army proved reluctant to adopt the new designs.

It examined the Colt Automatic Pistol, another of Browning’s designs, in 1902 and concluded that “this type of pistol has not yet reached such a stage as to justify its adoption in the place of the revolver for service use.”

Undeterred, Browning continued to refine and improve his designs, and when the US Army announced in 1910 that it would be holding trials to select a new service handgun, he had a new pistol ready.

The Army requirements were specific and ruled out many potential competitors, including the Luger. The new pistol had to be chambered for the new .45 ACP round. It had to be suitable for use by cavalry units, which meant that it had to be drop-safe and capable of operation while being held in the right hand.

Most of all, it had to be as reliable as a revolver.

Browning’s new design ticked all the boxes. It was designed from the outset for the .45 ACP round and, in addition to a manual safety on the left side, it had a grip safety. This meant that the pistol could only be fired when the rear part of the grip was compressed. This happened naturally when the pistol was gripped in the hand for firing but it meant that the weapon couldn’t fire if it was dropped.

During tests in 1910, the US Army discovered that the new pistol was also phenomenally reliable. In one test, 5,000 rounds were fired in a single session and when the pistol overheated, it was simply dunked in a bucket of water to cool it down.

Not many pistols would survive this sort of treatment, but the new design did not jam or fail to fire even once. Consequently, in 1911, the new pistol was adopted as the main sidearm of the US military with the designation M1911.

Like the Luger, the original M1911 wasn’t perfect. The rear sights were rather small and some people found the reach to the trigger to be too long.

Furthermore, shooters encountered the delights of “hammer bite” for the first time, where the web of skin between the thumb and index finger can be painfully nipped between the hammer and the frame when the slide recoils.

Into Combat

When America joined World War One in April 1917, for the first time the two pistols faced each other in combat.

On paper, the Luger probably looked like the superior weapon, being an example of precision-made advanced engineering. The Colt, by comparison, looked a little crude.

Pick up an early M1911 and you’ll almost certainly notice that the slide doesn’t fit particularly well on the frame, and it may rattle alarmingly if you shake the pistol. However, this also meant that manufacturing tolerances were less critical and the Colt could be produced more cheaply and more quickly than the Luger.

It rapidly became apparent in combat that what looked like disadvantages on paper proved to be benefits in the real world.

The Germans had by this time discovered the drawbacks to the Luger design. It simply didn’t work well in sandy, dusty, or muddy conditions. The fine tolerances in the toggle mechanism tended to jam much too easily.

Worse still, if a Luger was damaged, field armorers couldn’t just repair it with parts from another Luger – it had to be replaced with a completely new pistol.

In contrast, the Colt M1911 proved to be capable of shooting in just about any conditions. Its looser tolerances meant that it wasn’t likely to jam, even after being dropped in mud, and the .45 ACP round had much more stopping power than the 9mm Luger.

Parts were interchangeable between Colts too, which made field repair much easier. In the muddy trenches of Flanders, it became apparent that John Moses Browning’s design was simply a far superior combat weapon.

Use of the Luger in the German Army continued up to the late 1930s, though by then it was apparent that the gun was too expensive and too fragile ever to be an effective combat weapon. It was replaced in 1938 by the simpler Walther P.38, a design which ironically used some of Browning’s ideas.

The power and rugged simplicity of the Colt M1911 meant that it remained a service pistol long after the Luger had become little more than a historical oddity.

The M1911 underwent a minor upgrade in 1927 to become the M1911A1, and in that form it remained the principal sidearm of the US Army through World War Two, the Korean War, and the conflict in Vietnam. Iit was finally replaced in 1985, though some US military units continue to use the M1911.

No-one is quite certain how many examples of the M1911 design were manufactured by Colt and other companies, but most estimates suggest that well over one million have been produced. This gun proved to be a seminal weapon, and almost any modern semi-automatic pistol uses design cues taken from the Colt M1911.

Read another story from us: Evolution of the Sidearm – The History of the Pistol

The Luger design never really went anywhere after World War One. It was an iconic pistol and one which has proved popular with collectors, but it simply wasn’t as rugged or reliable as the Colt.

As a combat weapon, the relatively simple Colt proved to be far superior to the complex, precision-made Luger.