The Battle of the Bulge was one of the most important offensives of the Second World War. The final major offensive launched by the Axis powers along the Western Front, it was a fight that could have turned out a lot different, if not for the brave actions of First Lieutenant Lyle Bouck’s Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon.

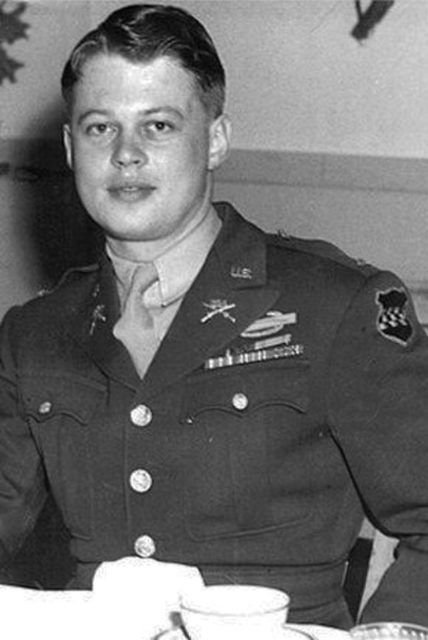

Early military service and the US entry into World War II

Lyle Bouck enlisted with the 138th Infantry Regiment with the Missouri National Guard at the age of 14. Despite his young age, he was a hard-working young man looking to earn money for his family, who was struggling financially. By 16, he’d been promoted to Supply Sergeant.

On December 23, 1940, the 35th Infantry Division was activated for one year of federal duty. Bouck’s regiment participated in the Louisiana Maneuvers, during which he was assigned as the Transportation Sergeant to the regimental Headquarters Company. While attending a transportation course, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, indefinitely extending his unit’s federal duty. They were then sent to California to defend against enemy invasion.

When his regiment was moved to the Aleutian Islands in May 1942, Bouck volunteered to attend either Parachute School, Officer Candidate School or the Army Air Corps. He was offered a spot at the Officer Candidate School and transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he underwent four months of intensive training. His performance drew the attention of his commanding officers, and in August 1942 he graduated in the top 10 of his class.

Following graduation, Bouck was retained to teach small unit defensive tactics to the next class at Fort Benning. He spent a year there before being transferred and assigned to the 99th Infantry Division, which was being deployed to Europe.

Arrival in Europe

Throughout World War II, Bouck was the first lieutenant in charge of Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, 394th Infantry Regiment, 99th Infantry Division, making him one of the youngest officers in the US Army.

The 99th Infantry Division arrived in La Havre in early November 1944, and by the end of the month was sent to the Ardennes region, relieving the 60th Regiment, 9th Infantry Division. Over the subsequent weeks, the platoon made up of two nine-man reconnaissance squads and a seven-man headquarters section, established and maintained observation and regimental listening posts, as well as gathered information.

As they were not trained for direct combat, they were kept from directly engaging with the Germans. However, this didn’t prevent them from conducting reconnaissance up to and through the German line, along with missions obtaining enemy intelligence and capturing German soldiers.

Holding off the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge

On the morning of December 16, 1944 – the first day of the Battle of the Bulge – Bouck’s platoon was in a defensive position, manning observation posts along the right flank of the 99th Infantry Division. They came under heavy fire from the advancing German 6th Panzer Army, later engaging in a 10-hour firefight.

In what later became known as the Battle of Lanzerath Ridge, Bouck knew how important it was to defend the Allied position, given its location along a road to Losheim Gap. He rallied his men together, along with four Forward Artillery Observers from Battery C, Field Artillery, and throughout the firefight moved along their position, despite exposing himself to enemy fire.

The platoon was able to hold over 500 German soldiers, wounding or killing 92. By dusk, they were out of ammunition and surrounded, allowing 50 German paratroopers to capture them.

Prisoners of War

Following their captures, Bouck’s unit was forced to walk two days to the village of Jünkerath, where they were loaded into boxcars and transported with other prisoners of war to Stalag XIII-D, before being moved to Stalag XIII-C. In the latter camp, enlisted men were separated from noncommissioned officers, who were sent to Oflag XIII-B.

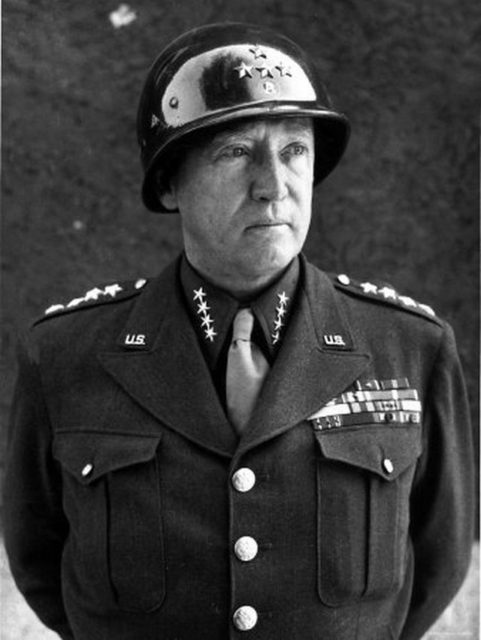

General George Patton‘s Task Force Baum raided the camp, during which Bouck pretended to be a field grade officer. He accompanied the force as they attempted to return to the frontlines, but they were largely captured or killed. Bouck, wounded, was returned to the camp and later transferred to Nürnberg, then Moosburg, where he spent the remainder of the war

Emaciated and suffering from hepatitis, Bouck was sent to hospitals in Reims and Paris following the camp’s liberation. He was then transported back to the US, where he was hospitalized in Springfield, Missouri.

Fighting for recognition

Unaware of just how outnumbered his platoon had been during the Battle of Lanzerath Ridge, Bouck considered the wounding and capture of his unit a failure. It wasn’t until later that he learned the true extent of their actions and the repercussions, in regard to delaying the German advance along the Meuse River and the north, in general.

The actions of the 99th Infantry Division remained largely forgotten, until 1965 when the Army published The Ardennes: The Battle of the Bulge, in which the platoon was briefly mentioned. This spurred one of Bouck’s men, William James (Tsakanikas), to reach out and encourage him to get his men the recognition they deserved.

Bouck’s contacted his former division commander, Major General Walter E. Lauer, who nominated Bouck for the Silver Star, which he received in June 1966. However, the rest of the platoon remained unrecognized, which angered him. He lobbied the government until, on October 25, 1981, a World War II Valor Awards Ceremony was held at Fort Myer, Virginia.

The entire platoon received the Presidential Unit Citation, while five members were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Four Silver Stars were handed out, on top of the one previously received by Bouck, along with 10 Bronze Stars with Valor. This made the platoon one of the most decorated in all of the Second World War.

Bouck continued his fight to have the entire unit recognized for their actions up until his death. When approached by author Alex Kershaw to contribute to the 2004 book The Longest Winter, he agreed, but with one condition, “I told him that other authors never wrote about the other men in the platoon, just me. I said I wouldn’t talk to him unless he promised that he’d also write about the other men.”

Post-war life

Following the war, Bouck returned to St. Louis, where he served as an Army recruiter. At one point, he applied for back pay for accumulated leave, to which the Army paid him the rate of an enlisted man. This infuriated him, as he’d been an officer while accruing the leave.

Bouck then went on to attend the Missouri Chiropractic College through the GI Bill, graduating in 1949. He practiced until 1997. He died on December 2, 2016, of pneumonia. Despite being eligible for burial at Arlington Cemetery, he opted instead to be laid to rest in his family plot at Sunset Cemetery in Missouri.