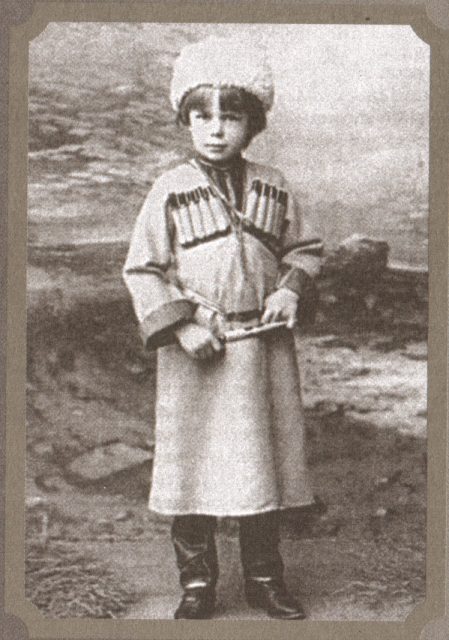

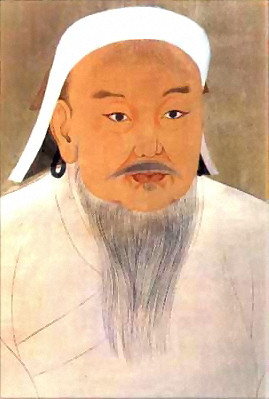

Although Roman von Ungern-Sternberg was born to a noble family of Austrian and Estonian heritage, it was his more distant Hungarian ancestry of which he was most proud. He claimed that, through this ancient bloodline, he was directly descended from Ghengis Khan. It was with this heritage that he would find the inspiration to become a Central Asian warlord in his own right.

Ungern’s life began in turmoil. When he was a very young child, his father was sent to an insane asylum. Shortly after, his mother divorced his father to marry another Estonian noble. As a result, Ungern and his mother moved from Austria to Estonia which, at that time, was a part of the Russian Empire.

From a very early age, it was clear Ungern was rather mad. He was known to bully other children ferociously and torture animals. On one occasion he is said to have strangled a relative’s pet owl to death. He was so violent and such a poor student that he had to drop out of school.

In addition to his antisocial characteristics, he was also remarkably elitist. Ungern boasted that his family, despite being only minor nobility, had “never taken orders from the working classes” and he despised the “dirty workers who’ve never had any servants of their own.”

These beliefs lent themselves to the formation of a reactionary pan-monarchist ideology. Ungern would, throughout his life, not only believe in preserving monarchies, but also in re-establishing them when they fell. Calling upon his heritage for inspiration, he decided that the way to do this was through conquest led by the traditionally horse-riding peoples of Southern Russia and Central Asia.

Ungern’s military career began after his father used his influence to get Ungern into a naval academy. Although his poor grades and behavior continued, Ungern soon joined the army instead of continuing his education. He served in the far eastern reaches of Russia during the Russo-Japanese war, although most historians believe he did not see any action.

While he was at the front, the failed Russian Revolution of 1905 began. Although monarchist forces defeated the revolution, many nobles were killed, and the peasants rose up to burn the historic Ungern-Sternberg estate. This only caused Ungern’s hatred of the lower classes to deepen.

In 1906, Ungern transferred back West to begin receiving education at an army military school in St. Petersburg. Surprisingly, he had become a much better student since leaving the naval academy.

During his time in St. Petersburg, he continued to develop a fascination with Buddhism, Hinduism, and sacred geometry that had begun in his teens. Although he remained a Christian, Ungern embraced some esoteric elements of Buddhism. He chose a unique set of beliefs that allowed him to continue drinking and being violent despite the non-violent nature of Buddhism.

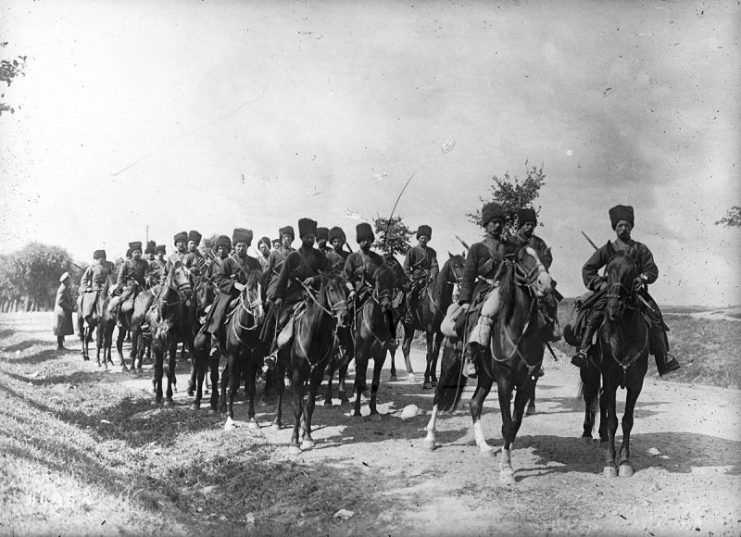

Less surprisingly, Ungern requested to be placed in command of a Cossack cavalry regiment upon graduation. Once this wish was granted, he traveled with several different Cossack regiments, deepening his interest and appreciation of the nomadic Central Asian cultures.

He quickly became respected for his talents as a horseman and a warrior. However, his violent behavior continued, including an incident where he was struck in the face by another officer’s sword during a drunken brawl. At one point, he was even kicked out of a Cossack regiment.

Despite all that, Ungern was made an officer when the Great War broke out. He was transferred to the European theater in 1914 as part of the 34th Cossack Regiment. He distinguished himself while fighting against German and Austro-Hungarian forces, and became especially renowned for his bravery.

He was known not only to volunteer for cavalry charges against entrenched enemies with automatic weapons, but also to ride at the front of such charges. Unsurprisingly, he was wounded five times.

Ungern won numerous awards for his bravery before getting in trouble for drunken brawls once again. However, this time the trouble was more serious as he was court-martialed and spent two months in prison.

He avoided being kicked out of the military entirely both because of his status as a noble and due to a need for as many men as possible to be in the Russian army.

After his release, Ungern was sent to the Caucasian front to fight the Ottoman Empire. By the time he arrived in January 1917, the Russian Empire was taking its final breaths.

When the February revolution overthrew the Romanov dynasty, Ungern was distraught. He worked with other officers in the area to begin gathering volunteer forces.

After seeing little action against the Ottomans, Ungern requested, and received, a transfer to the East to gather Mongol volunteer forces. It was here that he would amass his famed Asiatic Cavalry Division and fight against the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution.

Due to his ideology, Ungern was, of course, loyal to the Tsar. He was a supporter of the White movement during the Russian Civil War, although many Whites significantly differed from his ideology. Early in the war, he gained a significant victory by capturing and disarming a group of around 1,500 Reds.

However, with no central government to speak of, he soon began to conduct his own operations with goals that often ran counter to what his nominal superiors wanted.

He tried to gain the aid of Japanese soldiers as well as a Chinese warlord. He even went so far as to marry the warlord’s daughter in an attempt to secure an alliance.

As he established a de-facto independent rule just North of Mongolia, he started his own White Terror, where he executed anybody accused of being a Bolshevik or Jew.

Meanwhile, Mongolia had come under an opportunistic Chinese occupation after Russia’s government had collapsed. This was in violation of a previous treaty between Russia and China stating that Mongolia should be independent. It wasn’t long before Ungern’s own forces moved on Mongolia.

Ungern faced little opposition as he moved towards the Mongol capital of Urga (Ulaanbaatar). After a disastrous assault on the city, he came up with a new strategic plan.

The Bogd Khan was the de-facto ruler and religious head of Outer Mongolia, but he was under house arrest. After Ungern had launched a partially successful assault that allowed his severely outnumbered men access to the city, he had a special detachment rescue the Bogd Khan.

Taking inspiration from Ghengis Khan himself, Ungern had his men surround the city late at night and light numerous campfires to give the impression that they had far greater numbers.

The next day would see brutal fighting as his badly outnumbered forces repeatedly launched bold assaults on entrenched Chinese positions throughout the city. Through the use of explosives, battering rams, and brutal hand-to-hand combat, Ungern’s men won the day in a decisive rout of Chinese forces.

After the city was captured, the Chinese mostly withdrew from Mongolia, and remaining resistance was mopped up.

The Bogd Khan was impressed that Ungern had not only freed Mongolia from Chinese occupation, but had also executed a daring rescue of the Bogd Khan himself.

He rewarded Ungern with the titles of darkhan khoshoi chin wang and Khan. Although Ungern never declared himself to be a reincarnation of Ghengis Khan, some sources say that Mongols began to view him as an incarnation of the God of War.

Unfortunately, Ungern’s reign was a predictably violent one, as anyone accused of being a Communist or a Jew was subject to immediate extrajudicial execution.

Historian, Simon Sebag Montefiore, reviewed a recent book about Ungern, The Bloody White Baron, written by James Palmer. With excerpts from Palmer’s book, Montefiore describes the horrifyingly cruel executions:

“They suffered frenzied beatings (‘did you know men can still walk when flesh and bone is separated?’), being dragged by a noose behind moving cars or hunted through streets by Cossacks; there were beheadings, burnings alive, dismemberments and disembowelments, exposure naked on ice, the rending of bodies by wild animals, being forced naked up trees until they fell out and were shot and, finally, in Palmer’s evocative description, Ungern ‘sometimes ordered his men to bend back a tree, then bound the victim to it to be ripped apart by the branches when it was released.'”

Unsurprisingly, the now self-styled “Baron” Roman Ungern-Sternberg became a key target for Bolshevik forces once the Civil War turned in their favor.

The Whites had already been all but defeated on the Eastern front, so the Reds were able to turn all of their men towards Ungern’s cavalry division. The equipment that they committed to this cause included airplanes, armored vehicles, and machine guns.

Ungern moved his troops out of Urga in an attempt to invade Russia, but his attacks failed. In the meantime, the Reds took Urga. Now, without a base of operations, the Asiatic Cavalry Division began raiding further into Russia, essentially living the lifestyle of ancient nomadic raiders.

After capturing several minor settlements, Ungern realized that he could not succeed with only 3,000 men, so he retreated towards Mongolia. Realizing that their cause was lost, his men began to mutiny against Ungern’s seemingly directionless actions. They assassinated one of his fellow commanders and largely abandoned him.

Baron Roman Ungern-Sternberg’s inglorious end came when he was captured by Soviet guerrilla forces on August 20, 1921. After a show-trial on September 15, he was executed by firing squad.

Ungern got as far as he did in life mostly because of strings that were pulled for him, not on the basis of whatever merit he may have had. His absurd scheme to reinstate monarchy through the use of traditionally nomadic peoples fell apart. For the short time it lasted, his rule was one of utter brutality.

Read another story from us: The Stirrup: Genghis Khan’s Deadliest Weapon

Aside from his one significant victory at Urga, most of his battles were either defeats or insignificant in the grand scheme of the war. Yet despite his ultimate failure, some of his actions have had a significant impact on the world today.

It is entirely possible that Mongolia would be part of China if Roman Ungern-Sternberg had not forced the Chinese out.