A devout Christian, he joined the Nazi regime and then later tried to oppose it. When that did not work, he hatched a new plan – destroy them from within. As part of that plan, however, he had first to design the means of mass death used in extermination camps.

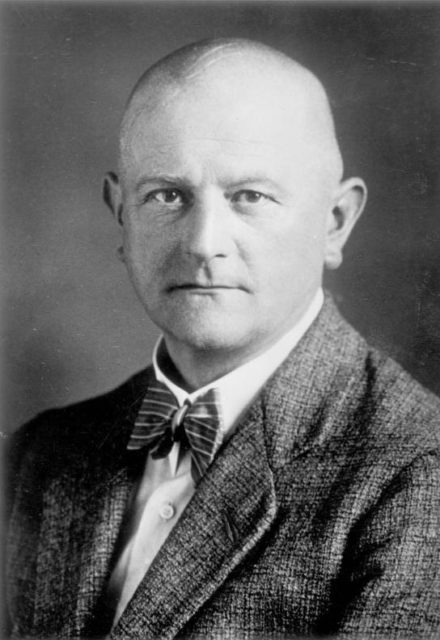

Kurt Gerstein was born on August 11, 1905, in Münster, Westphalia – then part of Prussia. The sixth of seven children, he grew up in a strict and traditional home which he rebelled against. His teachers claimed he was a lazy student who did not respect authority, so they were surprised when he graduated from high school.

To his family’s astonishment, he graduated with a degree from the University of Aachen in 1931 as a mining engineer. During his college years, however, he found religion.

During that period, many Christian organizations were enamored with Hitler’s socialist principles. Gerstein joined the Nazi Party on May 2, 1933. Two months later, he became a member of the Sturmabteilung (SA) – the original paramilitary group of the Nazi Party and the precursor of the dreaded Schutzstaffel (SS).

On April 4, 1933, Hitler tried to replace the 28 autonomous regional churches in Germany with a centralized Reich Church under Bishop Ludwig Müller.

Müller suggested that: (1) Christ was an Aryan, (2) “traditional Christianity” was “Bolshevism under a tinsel of metaphysics,” and (3) doing away with the Old Testament because of its Jewish character.

Not all Christians were happy with such views – Gerstein among them. His first salvo against the Nazi party, therefore, came in the form of a protest letter to Müller. In 1935, he attended a showing of “Wittekind” (an anti-Christian play written by Edmund Kiss) to disrupt it. He was beaten up, but that was all.

Then in 1936, Gerstein began distributing anti-Nazi literature – earning himself a six-week prison sentence. Upon his release, he was fired from his job at the Miner’s Association. He tried to become a priest, but when unsuccessful went back to protesting against the Nazi party.

Gerstein was arrested again in 1938 – this time leading to a six-month sentence. His party membership was revoked, meaning he could no longer work in the mining industry. In 1941, however, he embarked on his most harebrained scheme.

By then, the physically and mentally disabled were being euthanized; the fate of Gerstein’s sister-in-law. He rejoined the Nazi party to remove their suspicion of him and enable him to get a good job.

He joined as a member of the SS. That would put him in a good position to not only find out what was going on but also give him the opportunity to change them from within. He explained to his wife; he was becoming a Nazi as an agent of Christ.

In June 1941, the SS assigned him to the Hygiene Institute in Berlin where he designed water filters for soldiers and methods of vermin control. He so impressed his superiors they could not promote him fast enough. By January 1942 he was head of the Technical Disinfection Department – researching decontamination techniques.

Shortly after, Gerstein became part of a secret study on the effects of Zyklon B and other toxic gasses on human subjects. In the context of that research, he was sent to the German-occupied Polish town of Bełżec as part of Operation Reinhard – the Final Solution of Jews and others deemed undesirable.

What he saw became the basis of the still-controversial Gerstein Report; a document detailing what he knew of the genocide.

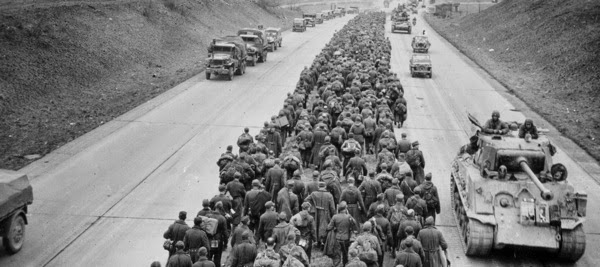

Gerstein arrived at Bełżec on August 15, 1942, as a train carrying about 3,000 Jews arrived from Lwow. He was shocked at how tightly they had been packed together – so much so that a number had died along the way from suffocation.

As they got off the train, the adult men were separated from the women and children. They were ordered to remove all their clothing and jewelry and form lines into a room where they were told they would be disinfected. Everyone was assured no harm would come to them so long as they cooperated.

Once packed into the room, they were sealed in. The diesel pumping engines were activated to propel monoxide into the chamber, but it broke down after a few minutes. The people inside started screaming, but no one outside cared. It took two hours to repair the machines, and another thirty minutes before everyone was dead.

When they pulled the bodies out, many had held onto each other so tightly they could not be pried apart. Soldiers then stepped forward to pull gold teeth out of their mouths and put them in buckets. Gerstein said he could not get over how blasé everyone else was about what they had witnessed.

The next day, he was on a train heading back to Germany. Another man in his compartment noticed how upset Gerstein was and asked if he was alright. That man turned out to be Göran von Otter – a Swedish diplomat based in Berlin. Gerstein told him what he had seen and begged him to pass the information on to the Allies.

Otter did so, but the Swedish government did not pass it on for reasons still being debated today. Gerstein continued to tell those he could, including Diego Cesaro Orsenigo – the Vatican representative to Berlin. Although Orsenigo told the Pope, the Vatican feared any confrontation with the Nazi regime.

Gerstein eventually surrendered to the French in the town of Reutlingen on April 22, 1945. He was interviewed by several Allied commanders and submitted his controversial report. There were many inconsistencies and exaggerations in it – although not about the mass killings.

Despite his report, he was treated as a Nazi war criminal and sent to the Cherche-Midi Military Prison in Paris, France. He committed suicide on July 25; whether because of the harsh conditions or because he felt guilty, remains unknown.

In August 1950, the Denazification Council in Tübingen concluded that while Gerstein may have been an unwilling participant in the Holocaust, he did not do enough to distance himself from it.