German and Italian aircraft strafed and bombed the defenseless civilians packed on the narrow road.

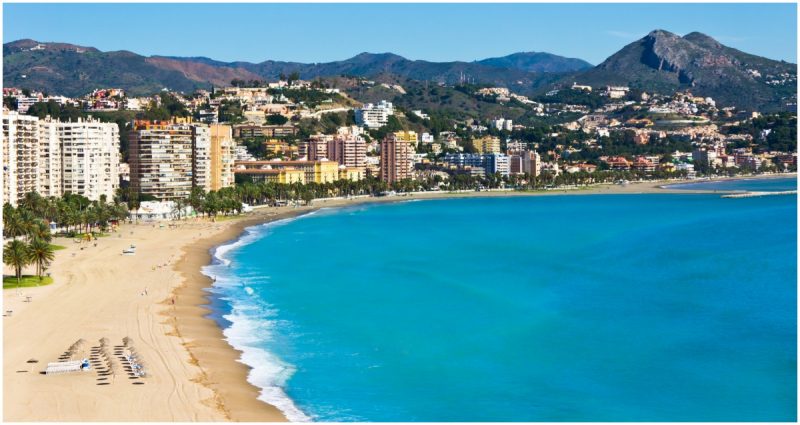

The N340 is one of the busiest roads in the popular holiday destination of the Costa del Sol in Spain. Few of the tourists who use it now are aware that this road was the site of a horrifying massacre in 1937.

The Spanish Civil War, like many civil wars, was fought with extreme brutality on both sides. However, the worst atrocity committed against unarmed civilians went almost unreported at the time and is virtually forgotten now.

The Spanish Civil War which began in the summer of 1936 saw Nationalist forces under the command of General Franco fighting against a confederation of groups who fought as the Republicans. The Nationalists were supported and armed by Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy and the Republicans were armed by the Soviet Union and supported by volunteers from the UK, the US and several other European countries.

By early 1937, the Republicans held much of the northern coast of Spain as well as the center, including Madrid, and parts of eastern and southern Spain. The Nationalists held the area close to the border with Portugal as well as the cities of Seville, Cadiz, Cordoba and Granada in the south. The Republicans also held a narrow strip of land in what is now the Costa del Sol which included the city of Málaga.

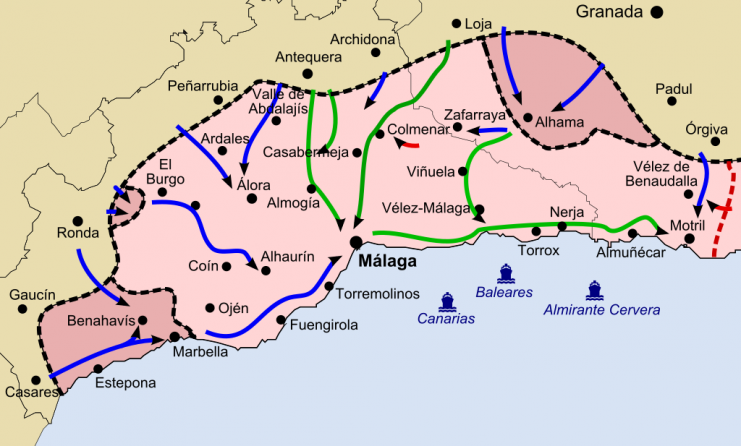

When the Nationalists were reinforced by the arrival of ten thousand Italian Blackshirts, equipped with tanks, who landed at the port of Cadiz, an attack on the city of Málaga made good strategic sense.

The Republicans who held the city were confident, but the truth was that they had little equipment or ammunition, no anti-aircraft defenses, and they were completely unprepared for mechanized warfare. When the Nationalist attack began on February 3, 1937, the nine Italian mechanized divisions broke through Republican defensive positions easily and began to head east, towards the city of Málaga.

On February 5, the Nationalist army approached the city. They were supported by German and Italian aircraft and by bombardment from three Spanish heavy cruisers, Canarias, Baleares and Velasco, and the German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee.

The fighting was bitter and intense and within a few days, the city fell to Franco’s troops. Almost as soon as the fighting was over, the executions began. Somewhere between four and five thousand people were arbitrarily executed by Nationalists in Málaga after the city had fallen.

This wave of executions and the destruction caused by bombardment and heavy fighting caused large numbers of civilians to flee to the east, along the coast towards the Republican-held city of Almeria.

It is estimated that as many as one hundred thousand people – mainly women, children, the elderly, sick, and wounded – set out on the 124 mile trek towards Almeria on the N340 road. A lucky few had transport or rode on donkeys. The vast majority were on foot, carrying their children and their few possessions.

The killings began on February 8 as the convoy of refugees reached the small town of Torre del Mar, nearly 19 miles east of Málaga. German and Italian aircraft strafed and bombed the defenseless civilians packed on the narrow road, and the three Spanish cruisers and the Graf Spee bombarded them from the sea.

There was no military justification for this – those who were fleeing were non-combatants. The decision to attack seems to have been a deliberate effort to terrorize these helpless people rather than to stop them.

For several days, the relentless attacks on those fleeing from Málaga continued. These reached a peak as the refugees made their way along the narrow, winding section of the N340 between the towns of Nerja (34 miles east of Málaga) and La Herradura (43 miles east of Málaga).

There was nowhere to hide in the rocky countryside and soon the road was littered with the bodies of the dead and the dying. Whole families were wiped out by strafing aircraft, and ditches and small valleys became filled with corpses.

The bridge over the Guadalfeo River, 56 miles east of Málaga, was bombed to slow the flow of refugees and to make them an easier target for the aircraft and ships, now assisted by pursuing Italian tanks. The massacre continued until the column of fleeing civilians finally reached the city of Motril, nearly 60 miles east of Málaga which was then still in Republican hands.

No one knows how many people died in the massacre on the N340. The most conservative estimates suggest at least four thousand, though the actual figure may be much higher.

The bodies of most of those killed were never formally buried – they were left in the rocky areas adjacent to the road or buried in shallow graves. Up to the 1960s and well beyond, human remains were regularly being discovered close to the N340.

Talk of the massacre on the N340 was suppressed during the years of the Franco regime in Spain – books by foreign authors which mentioned this event were banned. Even after the death of Franco in 1975, there was very little discussion of this event in Spanish histories of the Civil War.

For some reason, the killing of up to 1,500 civilians during bombing of the small market town of Guernica two months later in April 1937 became much more well-known. This was partly because the artist Picasso produced a dramatic painting which helped to focus the attention of the world on Guernica and the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

Strangely, Picasso, a native of Malaga, never produced any artwork to commemorate the killing of two or three times this number of civilians close to his home town.

Read another story from us: Shaping War in Europe – Lessons Learned in the Spanish Civil War

It wasn’t until 2005 that the first memorial service for the victims of this massacre was held in Torre del Mar, approximately halfway between Málaga and Almeria, and this has now become an annual event held on February 7 each year.

The massacre of unarmed and fleeing civilians was repeated many times in World War II. When Germany invaded France and Belgium in May 1940, German aircraft routinely strafed and bombed columns of civilians in an attempt to spread confusion and terror in advance of their army. They first learned how to do this on the N340 in 1937.