Auschwitz is a name that will live on through history as a dark reminder of the worst evils men are capable of perpetrating. Perhaps the most notorious of the German death camps, where it is estimated that over a million people were killed, the camp was the site of misery and suffering on a scale never seen before or since in human history.

It is often in the darkest places, however, that light can shine at its brightest. One such light in the dark horror of the camp was a Catholic priest called Maximilian Kolbe. At Auschwitz he made the ultimate sacrifice, heroically volunteering to die to save the life of a stranger.

Kolbe’s story began in Poland in 1894, where he was born to an ethnic German father and a Polish mother. Kolbe felt a calling to the priesthood from an early age. When he was twelve years old he claimed to have had a vision of the Virgin Mary, who offered him two crowns – one white, symbolizing a path of purity in life, and the other red, signifying the path of a martyr. He chose to accept them both.

In 1907 he enrolled in the Conventual Franciscan seminary in Lwow, and after this he studied in Rome, where he earned a doctorate in philosophy in 1915. He was ordained as a priest in 1918, and in 1919 returned to Poland, which was now an independent country. Once back in his homeland, he taught at the Krakow seminary, where he was quite vocal in his opposition to communist movements.

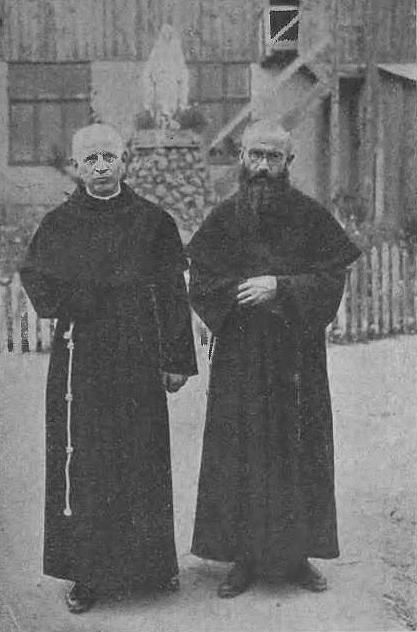

Filled with vigor and zeal, Kolbe kept working in aid of what he believed was his life’s greater purpose. He founded a Conventual Franciscan monastery at Niepokalanów near Warsaw in 1927, and then in 1931 moved to East Asia to spread the gospel there.

He founded a monastery on a mountainside on the outskirts of Nagasaki – that monastery would survive the nuclear blast from the atomic bomb dropped there in 1945, and is still an important site for Roman Catholicism in Japan today. After this he moved on to India, where he founded another monastery at Malabar, which was only operational for a few years. Ill health forced him to return to Poland in 1936.

In Poland, he started a radio station called Radio Niepokalanów. This was to be a short-lived project, though, because in 1939 Fuhrer invaded Poland. From then on nothing would ever be the same for Kolbe and millions of other Poles.

Many chose, understandably, to flee, when German troops came goose-stepping through the streets after having defeated the Polish Army. Kolbe, unlike many brothers at the monastery, decided to stay despite the threat posed by the German occupiers. It was a decision that was to prove fateful for him.

At his monastery, he organized a temporary hospital, but he was not able to run it for very long because he was arrested on September 19, 1939. He was released on December 8 when the occupants discovered his ethnic German ancestry.

Kolbe refused, though, to sign the Deutsche Volksliste, a German document officially recognizing him as an ethnic German, which would have granted him almost the same rights as any other German citizen.

Once released, he returned to his monastery and continued to help people in whatever ways he could. He and the other brothers hid any refugees who came to them for shelter, and they also printed and disseminated anti-war literature.

Eventually the community of refugees at the monastery grew, and it is estimated that Kolbe and his brothers helped 3,000 people there, including 2,000 Jews who were fleeing from German persecution.

However, the Germans had been keeping a close eye on the activities at Kolbe’s monastery, and in 1941 they decided enough was enough. They swooped in on February 17, shut the monastery down, and arrested Kolbe and a number of other men. Kolbe was first incarcerated at Pawiak prison, and then in May 1941 was transferred to Auschwitz.

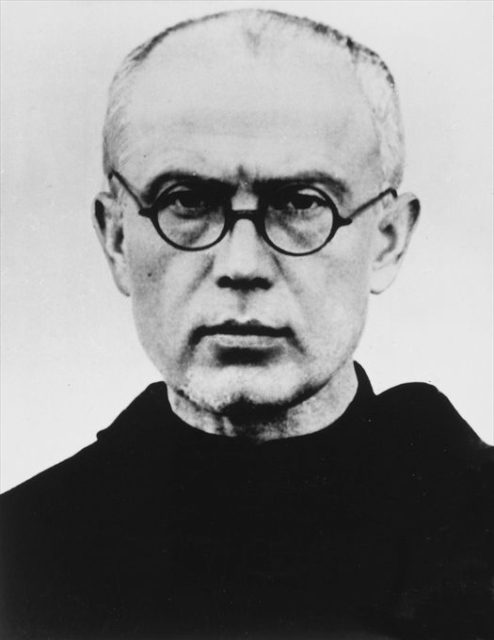

At Auschwitz, Kolbe – now simply called Prisoner 16670 by his opressors – continued to act as a priest, even in the face of brutal torture by the guards. The ultimate test of Kolbe’s faith came in July 1941, when a prisoner managed to escape from Auschwitz.

As a reprisal for the escape, and to deter future escape attempts, the camp commander randomly chose ten men to be killed in a particularly awful manner: they were to be starved to death.

When the guards picked out the last of the ten victims, a man called Franciszek Gajowniczek, this man cried out, “my wife, my children!”. Kolbe knew what he had to do. Knowing full well what his fate would be, he asked the guards if he could take Gajowniczek’s place. They agreed.

Auschwitz prisoner 26273

According to eyewitnesses, Kolbe spent his time in the death cell comforting the others and leading them in prayer. After two weeks of starvation, out of the ten prisoners only Kolbe was left alive, and the guards decided that it was time to put an end to his life. On August 14 he was given a lethal injection of carbolic acid – which he accepted calmly, steadfast in his faith until the very end.

Kolbe’s selfless act of heroism did not go unnoticed. In 1955 the Vatican officially recognized him as a Servant of God, and he was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1982. The memory of the noble and courageous sacrifice he made at Auschwitz will always be a reminder that even in the darkest places, light can always shine.