During the Second World War, the British pulled together a wide range of specialists to plan and execute covert operations. Working within the Special Operations Executive (SOE) or a specialist weapons research department labeled MD1, these men worked towards Winston Churchill’s stated aim of setting Europe ablaze.

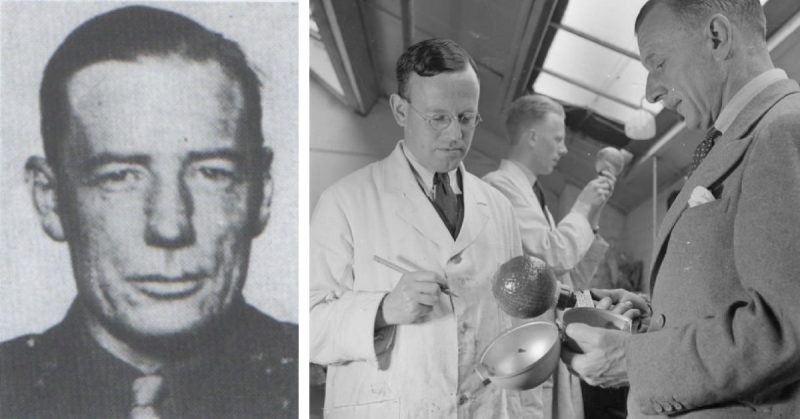

One of the leading figures at MD1 was Millis Jefferis.

A Soldier Engineer

Ruddy-cheeked and built like a bulldog, Jefferis created a distinct impression on those who met him. Gruff and impatient, he habitually dressed in crumpled clothes and chain-smoked his way through the day.

He was the image of a certain type of soldier: a rough, tough one with little respect for military etiquette. But beneath that grizzled exterior was a smart, inquiring mind.

Born in 1899 and trained at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, Jefferis was commissioned into the Royal Engineers in the summer of 1918. Arriving on the Western Front late in the First World War, he saw little action there.

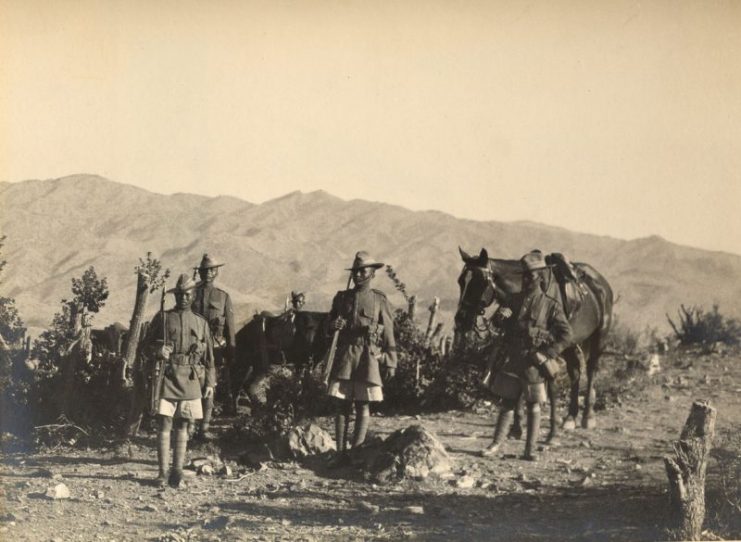

In 1920, Jefferis was sent to India, and it was here that his career took shape. During the Waziristan campaign of 1922, he built roads and bridges through supposedly impassable mountains, connecting the strategically important settlements of Isha and Razmak.

This work was carried out under regular fire from enemy snipers, demonstrating Jefferis’s courage in the face of adversity, for which he was awarded the Military Cross.

Though he continued to demonstrate a genius for bridge building, Waziristan brought out a new side of Jefferis. He became interested in guerrilla warfare and the use of explosives to destroy the very feats of engineering he was used to building.

Into Explosives

By the start of the Second World War, Jefferis was a major. He took part in the Norwegian campaign of 1940, using his specialist knowledge to destroy bridges ahead of the Germans as the Allies retreated north.

After Norway, Jefferis was set to work developing specialist armaments, first in Military Intelligence Research and then, when that organization was folded into SOE, as a leading figure in MD1.

Here, Jefferis was given free rein to explore his passion for destruction. He specialized in designing the weapons used by SOE’s army of secret agents and saboteurs, working on his own inventions and overseeing the work of others. Fascinated by the potential of algebra, he used complex mathematics to define and refine war-winning weapons.

One of Jefferis’s first ideas was for a magnetic mine that could be attached to the underside of enemy vessels by swimming saboteurs. Without time to work on this himself, he sought out others for the task, recruiting science journalist Stuart Macrae and through him the caravan designer Cecil Clarke.

This partnership resulted in the limpet mine, used in sabotage operations both on land and at sea.

Work at the Firs

In the early days of the war, Jefferis was hampered by supervision from the Ministry of Supply. For SOE, the timely delivery of weapons was important, but the Ministry, responsible for all munitions purchases and wary of this strange research team, slowed down the purchase of Jefferis’s creations.

A man with little patience for bureaucracy, Jefferis began working around civil servants and politicians to get the job done.

Fortunately, his creations won the favor of the most important politician in the country: Prime Minister Winston Churchill. After a dramatically destructive demonstration of one of the weapons at the Prime Minister’s country residence, Churchill threw his enthusiastic support behind Jefferis.

Jefferis’s early work took place in an office on Caxton Street in London, but this was not a suitable place for practical testing. The department set up an out-of-town research facility called the Firs, where expert engineers invented, tested, and demonstrated their wild weapons. It was the perfect place for Jefferis.Freed from interference by the Prime Minister’s favor and the isolation of the Firs, Jefferis was free to pursue his work. He roamed the facility, his pockets full of wires, batteries, and detonators, working on his own creations and consulting with other inventors on theirs.

He worked long hours in the service of the vital war effort and expected the same from his staff, demanding sixteen hour working days and few days off.

Neglecting family relationships in favor of his work, Jefferis nearly ruined his marriage. His wife, Ruth, almost left him, before deciding instead to get a job at the Firs, so that she could see more of her husband.

Jefferis’s weapons, which ranged from mines to mortars to specialist ammunition, were soon in use all over the world, from resistance operations in Europe to anti-submarine warfare in the Pacific. Military and political figures increasingly recognized his special genius and came to consult with him on armaments.

In recognition of his work, he was made a Commander of the British Empire in the 1942 New Year’s Honours list, a prestigious reward for a man whose work was largely secret.

After the War

When the war in Europe ended, Jefferis joined celebrations at the Firs in uncharacteristically wild style, tearing around the grounds in a tank. Then he went straight back to work on weapons for the Pacific war.

In late 1945, with the war finally over, Jefferis was made Chief Engineer to the Indian Army. He was also promoted to acting major-general and made a Knight Commander of the British Empire, rewards from a grateful Churchill.

He spent five years in India and Pakistan, returned to England as a brigadier, and served as an aide to King George VI from 1951.

Retiring from service in 1953, he was given the honorary rank of major-general.

Millis Jefferis died in 1963. The secrecy around his wartime work meant that his importance was little recognized at the time. It is only with the passing of decades that the veil of secrecy has lifted and the world has come to recognize his extraordinary work.