In 1345, the city of Caffa was razed by a vicious pandemic, in what would, centuries later, be recognized as the first use of biological warfare in history.

After successfully repelling the first Mongol siege in 1343, Caffa certainly expected Jani Beg, the leader of Mongols, to strike again. But when he finally did, in 1345, he did not just come roaring with his Mongolian army, he came with something else, something more sinister: The Black Death.

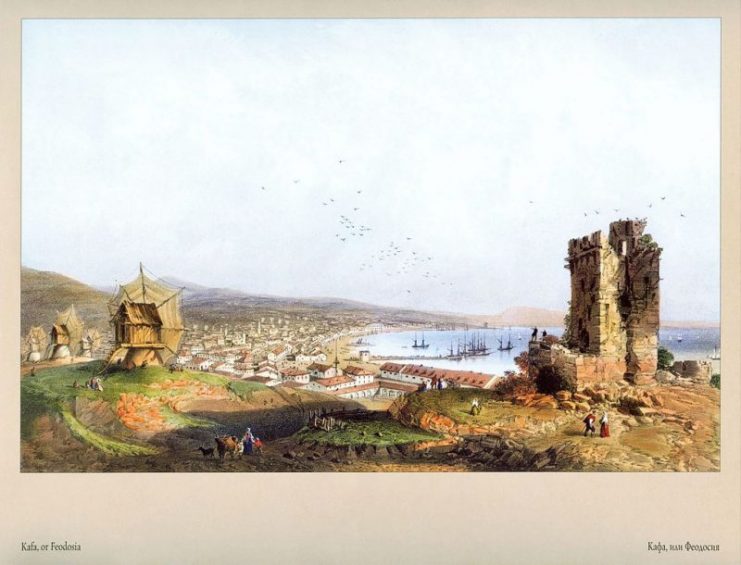

Caffa (present-day Feodosiya) was a city set in Crimea, on the northern coast of the Black Sea. After the capture of Crimea in the 1230s, the city of Caffa came under the dominance of the Mongols.

The Mongols in the late 13th century allowed a group of traders from the Republic of Genoa to establish a trading settlement there. Due to its successes, Caffa virtually monopolized trade in the Black Sea region. It became a major seaport, housing one of Europe’s largest slave markets.

The Mongols benefitted immensely from the Genoese businesses in the bustling city as it earned them access to Italy’s largest commercial center while stimulating trade across its vast empire.

However, while many of the Mongols had been practicing Muslims from the 1200s, the Genoese merchants were Christians. This religious disparity between them would occasionally result in disputes—pallid embers of hatred that would grow in strength as conflicting beliefs fanned and fed them.

These embers of hatred would burst into flames in 1343 in the city of Tana. After a fight between Genoese Christians and the local Muslims in Tana, one Muslim local was found dead.

Sensing the trouble that loomed like pregnant clouds over their heads, the Genoese fled to Caffa where they were granted protection.

Not so long after their flight, the Mongols came after them. They demanded the city hand over of the culprits. It came as a shock to them when Caffa refused. Infuriated, Jani Beg chose to attack. So, in 1343, the Mongols laid siege to the city of Caffa.

Caffa did not turn out to be as feeble as the Mongols expected. Staring the Golden Hordes in the face, Caffa struck back in defense. Caffa had access to the sea and they made adequate use of this, bringing in supplies and reinforcements from Italy. The first siege ended after the Mongols retreated, suffering about 15,000 deaths and heavy damage to their siege equipment. Jani Beg took his army home, but his mind still raged.

In 1345, Jani Beg returned, bearing more than just his siege machinery.

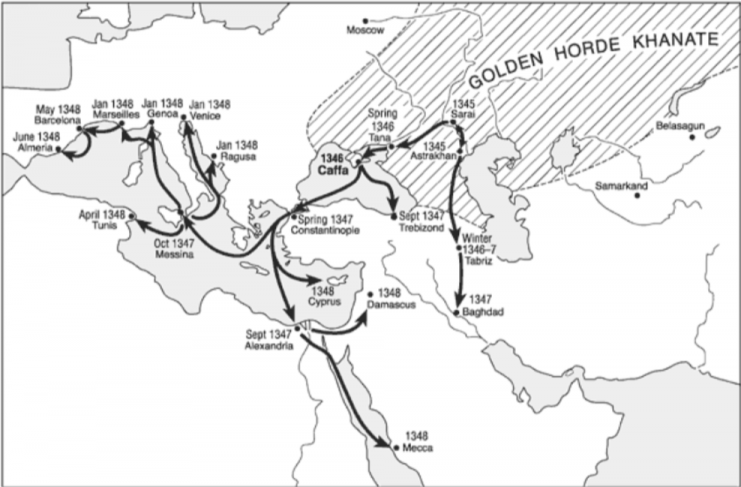

The Black Death was a plague which had been ravaging Central Asia since 1331, it was said to be caused by Yersinia Pestis and is present in fleas carried by rodents. It traveled along Silk Road as rodents migrated from Asia’s famine-ridden lands until it came to Crimea when the siege was ongoing.

While the Mongols laid siege to the city of Caffa, they were struck by the plague. According to an account of the events of Crimea, the Tartars (Mongols) were suddenly struck by the pandemic. Falling on all sides as though they had been struck by thunder, with lumps on their joints and dark marks on their faces, they developed a putrid fever and were beyond help, neither from doctors nor their god.

The spread of the plague through the ranks of the Mongols demoralized the army, and a large bulk of them lost interest in the siege. However, the Mongols would not back off, not without giving Caffa a piece of their own torment.

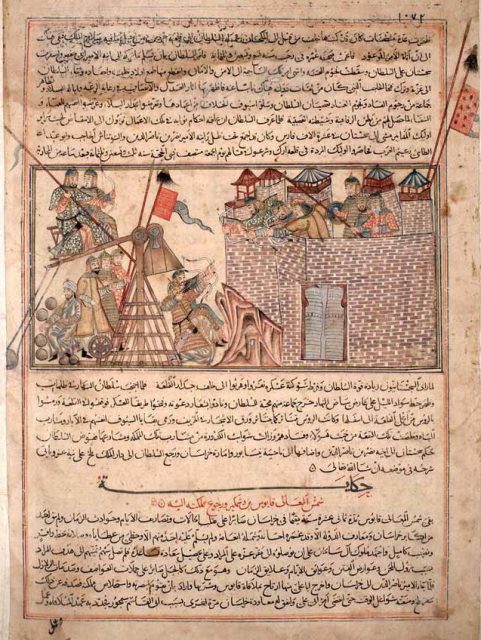

They put the corpses of their dead on their catapults and flung them over the defensive walls of Caffa.

The dwellers of Caffa watched as rotten bodies fell from the skies, crashing on their soil, spreading their putrid smell in all directions. The Christians could neither hide nor flee from the havoc that rained down upon them. They moved as many rotten bodies as they could, dumping them into the sea as quickly as they could. But by then, it was too late; the Black Death was already in Caffa.

The siege ended in 1347, after negotiations between the Mongols and the city, but by then the plague had begun its work.

Those who were still alive fled Caffa in ships sailing to Europe. They fled with their lives, taking the Black Death along with them. They made a stops Constantinople, unconsciously infecting the city. Thousands of people died in the ensuing disaster, including Andronikos, the son of John VI Cantacuzenos, a Greek Emperor.

Those who were still alive fled the city, but they fled too late. They fled in several directions away from Constantinople, taking the plague with them. By autumn, the western coast of Asia Minor was experiencing a major breakdown from the results of the dreadful pandemic.

The fleeing merchants would finally get to their homes in Italy, unaware of the death that followed them closely, like a shadow.

In the end, the Black Death was responsible for 75 to 200 million deaths in Eurasia.

Having killed between 30-60% of Europe’s population, and about half of China’s population, it is one of the most devastating plagues in history, and it marked the earliest use of biological weaponry in the history of warfare.