To make the most of what a horse can offer in military terms, a cavalryman has to be an excellent rider.

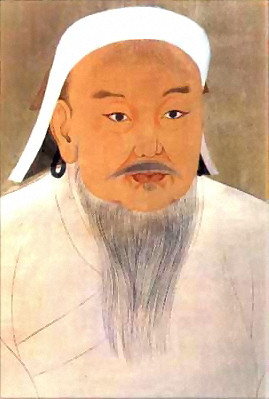

Genghis Khan and his Mongol warriors were one of the mightiest military forces in all of human history, conquering an area of over nine million square miles in the thirteenth century and subjugating almost a quarter of the world’s population.

It seemed that no kingdom or empire could stand against them. The Mongols won victory after victory, crushing any army that attempted to stop them. How they were able to achieve such a monumental feat and win battle after battle was due to a number of factors, but at the core of their immense success was the mighty Mongolian mounted archer.

The Mongols under Genghis Khan fielded a huge force of essentially light cavalry, perhaps the largest ever seen in history. Furthermore, each mounted archer had four or five horses which he would switch between over the course of a day, ensuring that no single horse got too tired and overworked.

In this way, Mongol armies were able to cover vast distances in a short time, and they outpaced their enemies by a huge margin. A large Mongol force could easily cover 60 miles or more during a day, with specialized scout forces being able to cover up to 200 miles in a day.

This kind of mobility was unheard of in the thirteenth century and gave the Mongols an incredible advantage over their enemies.

But how were they able to cover these vast distances and achieve such levels of mobility, even with four or five horses per warrior? The answer to that question lies in both the horses they used and the men who rode them.

The horses used by the Mongols were small and light. They would have been regarded as ponies in comparison to larger mounts such as the powerful horses ridden by contemporary European knights.

However, the small horses of the Mongols did not lack for speed and were exceptionally hardy beasts, able to weather extreme climates and graze off almost any available grass. This meant that huge numbers of horses could be moved without worrying about carrying fodder for them. They could quite literally live off the land wherever they went.

Interestingly enough, a period of climate change in the thirteenth century may have contributed to the success of the Mongol hordes.

A recent study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science indicates that the rise of Genghis Khan and his rapidly expanding empire occurred right after a period of significant climate change to the Mongol steppe.

In the years just before Genghis Khan’s rise, an extended period of drought gave way to a period of abundant rainfall and mild temperatures, which would have meant that the grasses of the steppe flourished – providing plenty of food for the tens of thousands of horses of the roaming Mongol armies.

Of course, to make the most of what a horse can offer in military terms, a cavalryman has to be an excellent rider, and Mongolian mounted archers were some of the best horsemen the world has ever seen.

It would be no exaggeration to state that they grew up in the saddle. They were nomadic by nature and learned to ride and hunt from horseback from a very early age. Like their horses, they were hardy people who could easily live off the land and shrug off difficult conditions in the field.

Because they were so well-adapted to life in the saddle, they could not only cover vast distances on horseback, but they could also perform tremendous feats of agility and speed on their horses, which translated perfectly to rapid maneuvering in battle.

Furthermore, because Mongol warriors were usually lightly armored, preferring light leather or padded cloth armor to steel (although they did make use of heavily-armored units for shock charges as well), they were able to move with speed and maneuver easily.

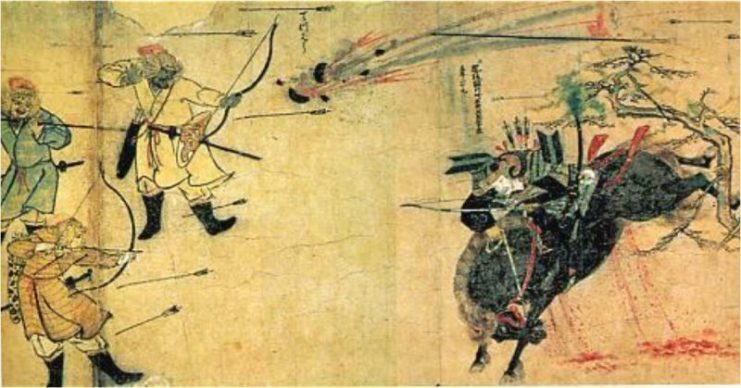

The bows they used also contributed greatly to their military prowess. Mongol bows were composite recurve bows made of bone, wood, and sinew. While they may have looked small, especially compared to something like a six-foot English longbow, these bows were capable of tremendous range and power.

With an effective range of over 400 yards and capable of accurate shots almost up to 200 yards, Mongol bows were undoubtedly deadly weapons, especially in the hands of an archer who had been trained in their use since an early age.

Armed with these weapons, the highly agile and speedy Mongol armies could easily flank or encircle an enemy army, raining down a storm of deadly arrows on them.

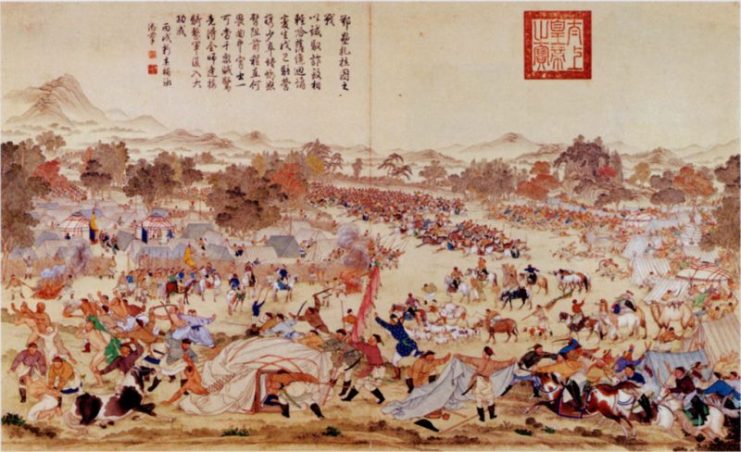

In terms of tactics, the Mongols were masters of strategy. They would pick battlefields and fight on terrain that they could use to their advantage, rather than allowing themselves to be drawn into battle on terrain unsuitable for their style of warfare.

If battle did occur on unsuitable terrain, they would feign a retreat or rout to draw the opposing army – often over large distances – to a place that would better suit their tactics. Then they would turn around and annihilate them.

A major factor in their tactical superiority was the fact that they were willing to learn from the people they conquered. If there were any ideas and strategies belonging to their foes which the Mongols considered beneficial, they would adapt them to their own use.

For example, the Mongols employed Chinese and Khwarzameian siege experts to construct complex siege machinery and design strategies when laying siege to heavily-fortified cities.

Meritocracy and a spirit of egalitarianism also contributed enormously to their military success. Every Mongol soldier was entitled to shares of the spoils of war, and even high-ranking commanders were required to do menial tasks.

Any man who showed promise and talent and who worked and fought hard was liable to get promoted. The generals were not, as they were in the rest of the world, high-born men who were born into their positions, but rather warriors who showed an exceptional talent for command and strategizing. Their place and circumstances of birth were irrelevant.

The Mongols also ensured that tribal loyalties were removed from the equation by separating men – especially those from conquered peoples, who were liable to rebel – from their friends and members of their tribe or ethnic group. These men would be put into units with foreigners and strangers.

The Mongols did allow conquered people to retain a lot of their native customs, though. All religious beliefs were tolerated, and nobody was forced to convert to a new religion. In this way, the barriers of culture and tribe were resolved, and these men forged new ties of brotherhood with the men in their unit.

Units were strictly organized according to numbers. The smallest was an arvan, consisting of ten men, and this went all the way up to a tumen, a division of 10,000 warriors.

Discipline was also extremely strict. While the Mongols were fair and embraced principles of egalitarianism, they knew that an army without discipline would be useless. Punishments for even the most minor infractions were swift and harsh, with death being a common punishment for even light offenses. In this way, troops were kept well-disciplined and loyal.

Read another story from us: Genghis Khan: A Visionary Leader or a Brutal Conqueror?

The resounding military success of the Mongol hordes was an almost unequaled feat in history, but without the extreme mobility, hardiness, discipline, and loyalty of the horsemen who made up the bulk of the Mongol armies, Genghis Khan and his successors would never have achieved what they did.