For six years, the Chinese commander Lu Wenhuan held out against the Mongols and defended one of the twin cities of Xingyang and Fangcheng.

However, undermined by an incompetent commander of Fangcheg and with a hack in overall command, both cities were ultimately doomed to fall.

Between their rise in the early thirteenth century and the beginning of their campaign against the Song dynasty in 1259, the Mongols ranged through Europe from as far west as the Adriatic Sea (on the east coast of Italy) across the Middle East.

But the wealth of southern China, as well as the sometimes-inept performance of the Chinese armies, enticed them in that direction.

Southern China had the advantage of terrain. The Southern Song dynasty effectively relied on the rivers and rough terrain of southern China to thwart their attacks.

The Mongol advance got bogged down in the Sichuan basin. This made the Mongols shift focus from the Sichuan valley to the pivotal cities of Xingyang and Fangcheng.

Xingyang and its twin city across the river were vital for control of the Middle Yangtze region. The region was also the launching point of Song counterattacks against their enemies, including the Mongols.

The western city of Xingyang was protected by mountains on three sides and the Han River on its east. The city of Fangcheng had the river on its west and was relatively exposed on its east side, so the siege started there.

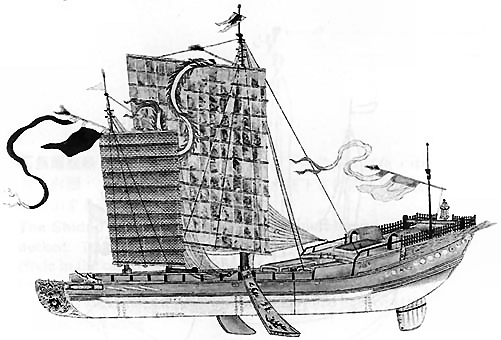

The first thing the Mongols did was to isolate the cities and fight off the Song navy which would be the chief avenue of supply to the cities.

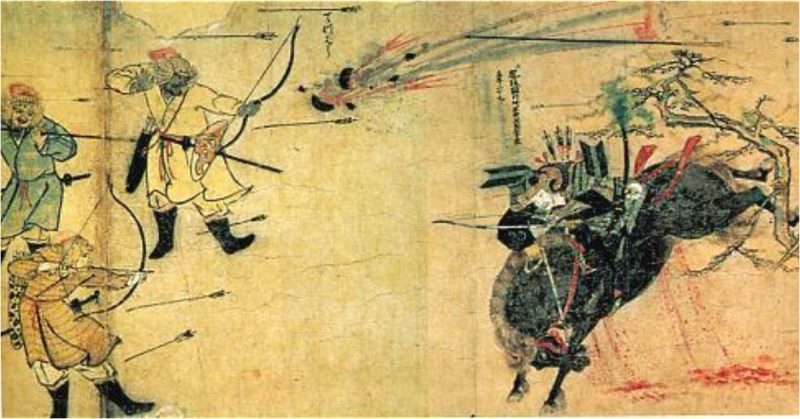

Through a series of bitter battles and fire attacks, the Mongols burned most of the Song ships and the bridge between the cities.

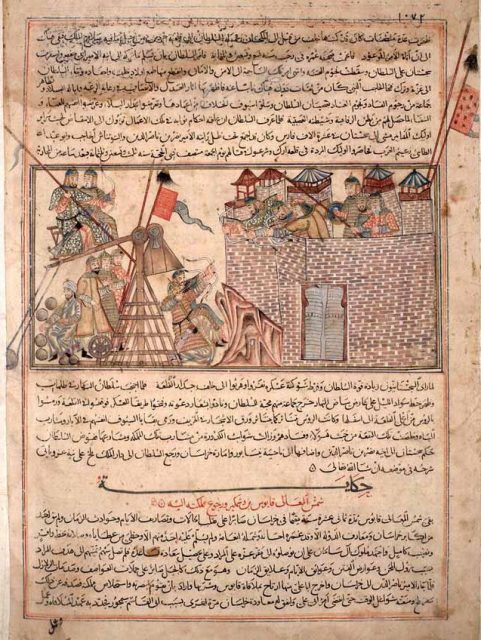

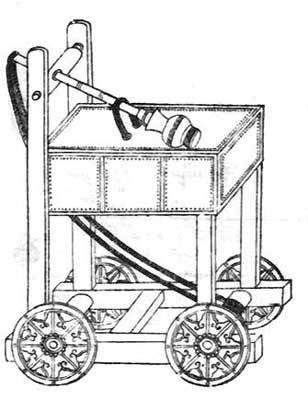

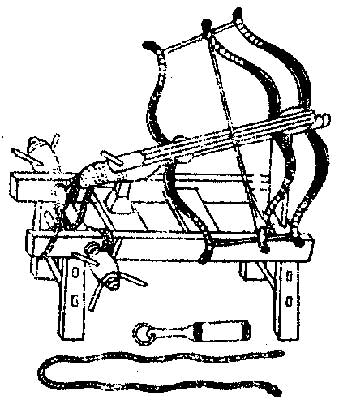

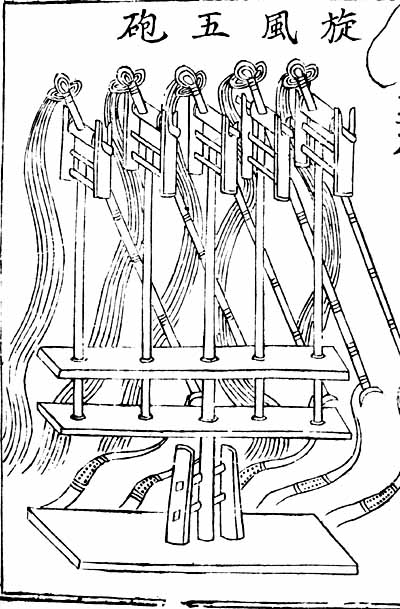

Under a hail of Song arrows from Fangcheng, the Mongols set up their Muslim-engineered trebuchets. To counter these devastating machines, the Chinese developed special nets that largely negated the effect of the trebuchets.

Despite this, the Mongols continued to exercise a stranglehold on Fangcheng.

However, the Song court had political problems that ultimately aided their enemy.

The Lu clan, headed by Lu Wende, had significant ties with the Song court. The clan also had family members in very important commands.

Lu Wende, officially called the military commissioner of Jinghu, held overall command of the region. His brother, Lu Wenhuan, commanded Xingyang, while Wende’s cousin commanded the other twin city.

Unfortunately, Lu Wende died during the early days of the siege in 1270 which disrupted the unity of command that the family had enjoyed in the region. He had been one of the few generals to defeat the Mongols before. He had cultivated good relations in the capital through a network of relatives and friends.

His death inspired the chief minister to appoint a new commissioner. Unfortunately, the decision was based more on the new individual’s political connections than the military needs of the defense.

As a result, the new overall commander appointed to defend the twin cities was a political hack called Li Tingzi.

Tingzi was resentful of the power that uncultured military men like the Lu family held with the court. In addition, the court in general was nervous about the Lu clan and didn’t want to grant the remaining members of the clan any more power.

Due to his incompetence as a commander, Tingzi was largely unable to coordinate a broad strategic response from the Song dynasty to relieve the siege of Fangcheng. He managed only a few partial resupplies, with thousands dying upon each attempt.

Worst of all, his appointment, which bypassed the capable defenders from the Lu clan already fighting in the twin cities, signaled to the clan that they had lost the confidence of the court.

Despite the inept attempts at resupply by Li Tingzi, the skillful command of the Lu clan combined with the impressive defensive advantages of the city meant that it still held for a long time.

By early 1273, six years into the siege, the Mongols had upgraded their trebuchets, and the Song forces had run low on food supplies.

Under cover of raging snowstorms as well as the thunderous impacts of massive hurled stones, the Mongols assaulted Fangcheng from every side (including an amphibious assault from the river to its west).

The Mongol attackers suffered horrendous casualties, and many commanders from both sides were severely wounded as the attacking soldiers filled trenches surrounding the walls (often with their dead bodies), stormed the walls, burned the city, and took part in desperate hand-to-hand fighting in the streets.

The Mongols killed everybody in Fangcheng and stacked their bodies in a huge pile. The bodies of 10,000 men, women, and children rose higher than the walls of the city and could be seen from Xiangyang.

Lu Wenhuan assessed the situation. The Mongols had removed the defector Lui Zheng far to the rear to avoid angering Lu Wende. Lui Zheng had been a skilled commander who was alienated from the Song court shortly before this siege. Subsequently, he actually became a trusted adviser on the Mongol side.

Readers might assume that Lu would never join his enemy after a bitter fight that lasted most of a decade (and killed his family members). But generals had an obligation to save the men under their command from useless slaughter.

On a philosophical level, he could justify his defection if he believed that his rulers had lost the Mandate of Heaven.

Furthermore, the Mongol’s removal of a rival general was a key sign of respect which showed Lu he might defect successfully.

Lu had fought for over six years with little resupplying. The knowledge that his city could fall like its sister across the river and its inhabitants would receive the same fate, combined with his continued alienation from the court, made him ready to concede defeat.

The Han River, a path to the Yangtze, and the heart of the Song dynasty were now open to the invaders. When the Mongols finished building a fleet, Lu Wenhuan led the way and convinced many others in his family network to defect.

This started a cascade of defections from most military leaders and, combined with the strategic advantage of a larger fleet flowing downriver, the last Song Emperor capitulated a mere three years after the fall of Xingyang.

The Mongols were an impressive military machine that showed they were more than nomadic cavalry. They could develop combined arms such as infantry, marines, and siege equipment.

Nevertheless, the Song dynasty had the resources and talented leaders to beat them. In many ways, it was the political decisions of the Southern Song court — such as its failure to adopt a proactive strategy, the alienation of key generals such as the Lu clan, and political appointments and divided command — that undermined the twin cities.