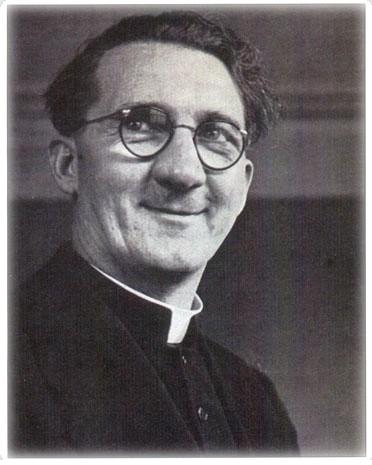

He was a man of many faces who used his talent at disguise to help thousands of people escape from the Nazis. Hunted by them, he ended up converting the SS chief in Rome.

Hugh O’Flaherty was born on February 28, 1898, in County Cork, Ireland. He was raised in Killarney where his father was a steward on a golf course where the family lived. Hugh became a scratch golfer – meaning he was quite good.

He was intelligent earning a scholarship to a teacher training college. Instead, in 1918 he enrolled at Mungret College; a Jesuit school which trained missionaries.

The Irish War of Independence broke out in 1919, making life difficult. In 1922 O’Flaherty was sent to Rome to finish his studies where he was ordained three years later.

Impressed with his abilities, he was appointed to the Holy See; the Vatican’s governing body. He served as the Vatican’s diplomat to Egypt, Haiti, Santo Domingo, and Czechoslovakia. In 1934, O’Flaherty was appointed Monsignor; a title for high-ranking clergy members who have provided valuable service to the church.

O’Flaherty never lost his talent for socializing or forgot his golfing skills. He mingled with Victor Emmanuel III, the King of Italy and he also became friendly with Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini; the founder of Italian Fascism. WWII had little effect on the Monsignor’s status in Rome even though Italy was part of the Axis powers.

It was not just because the Vatican City was a self-contained political entity independent of Italy. It was also because the Republic of Ireland was neutral during the war. Therefore, he was allowed to visit POW camps throughout Italy. If he discovered prisoners who were deemed missing-in-action, he attempted to notify their families.

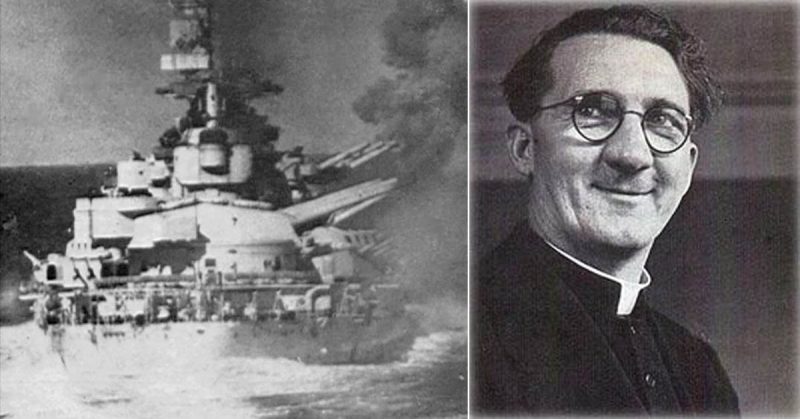

By 1943, the Italians had suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of the Allied powers. They deposed Mussolini and freed all Allied POWs. Germany was furious at the betrayal and retaliated by invading Italy. With a portion of Italy under German occupation, those POWs were at risk of being recaptured. The Monsignor decided to help.

O’Flaherty enlisted several VIPs. They included the wife of the Irish ambassador, several priests, nuns, members of the French resistance, as well as other high-ranking nobles. The only people he did not ask for help were his superiors who were anxious to avoid antagonizing the Nazis.

It is estimated his group hid over 6,500 people for the remainder of the war in farms, convents, churches, and private apartments. Although most were Allied soldiers, some were Jews.

It did not take the Nazis long to realize that O’Flaherty was behind the disappearing people. Fortunately, they did not storm the Vatican because of its unique status. As they already had so many enemies, the last thing they wanted was to alienate the world’s entire Catholic population by violating the Pope’s domain.

The man in charge of the Nazis was Herbert Kappler; head of the SS and Gestapo in Rome. Kappler ordered a white line painted at the entrance to St. Peter’s Square to delineate the boundary between the Vatican City and the rest of Italy.

O’Flaherty was told he would be shot if he crossed the line – not that it stopped him. To get about, he donned various disguises, hence his nickname “the Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican.” It came from a book about an Englishman who disguised himself to help French nobility escape the purges of the French Revolution.

O’Flaherty did not just hide POWs. He also coordinated the rescue of downed pilots, providing them with food, medicine and safe houses throughout Italy.

By the time the Allies captured Rome in June 1944, O’Flaherty’s underground network had kept 6,245 Allied escapees alive. Of the city’s 9,700 Jews, 5,000 were hidden by the Vatican at different properties, and 3,700 were hidden by O’Flaherty’s group. 1,007 were shipped to Auschwitz.

Kappler’s days were over. For his role in several atrocities, including the Ardeatine Massacre (the slaughter of 335 civilians in the Ardeatine Caves), the Nazi chief was sentenced to life in prison. While there, he asked to speak to the Monsignor and was probably surprised when O’Flaherty agreed.

Over the years, the two developed a strange friendship. Raised a Protestant, Kappler wanted to convert to Roman Catholicism, but O’Flaherty cautioned against it. The priest believed it might be misinterpreted as an attempt to influence his trial judges. He would be Kappler’s only visitor until 1959.

After his sentencing (which upheld his lifetime conviction), Kappler went ahead with the conversion. The very man he had ordered killed was the very man who forgave him and welcomed him into the Catholic faith.