On January 23, 1968, a run-down environmental research ship was conducting oceanographic studies when it was surrounded by North Korean naval forces, which demanded its surrender. As it happens, the environmental ship was actually a badly disguised spy ship, and what was about to go down would be the first hijacking of a U.S. naval vessel in 153 years.

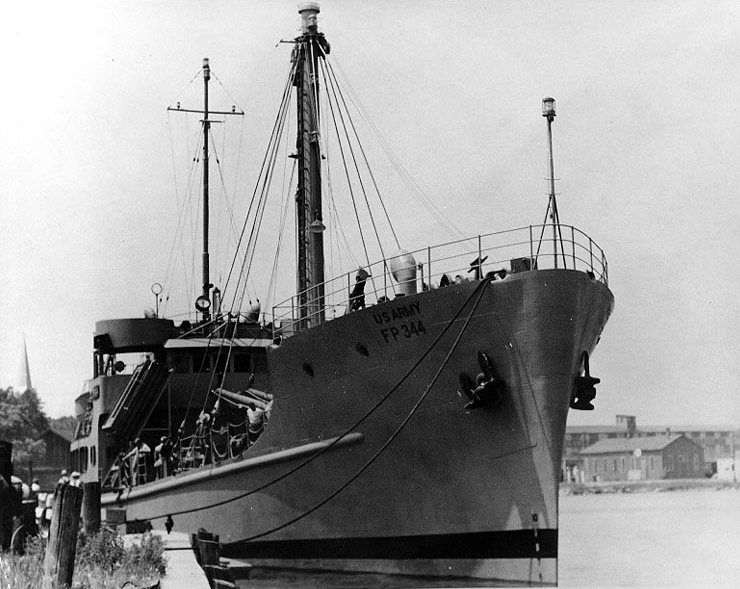

USS Pueblo, with the initials GER2 painted in white on the hull, had the real mission of listening to and decrypting secret North Korean communications while sitting just outside the 12 nautical mile limit that marks the edge of national territorial waters. To that end, the ship had state-of-the-art cryptologic equipment onboard.

What it didn’t have was adequate weapons to defend itself. The ship only had about two dozen army rifles which were not insulated against the frosty temperatures they would be facing on this mission, meaning they would surely jam. There had also been an assurance that backup forces would be on call to help if anything went wrong, but such forces weren’t dispatched when things did indeed go wrong.

This was not the first mission for a vessel of its type. Its sister ship, USS Banner, had been conducting similar missions for a while. Although Banner was never intercepted, its presence prompted the North Koreans to state that they would not tolerate any intrusion on their territorial waters and that this stance would be enforced with maximum prejudice.

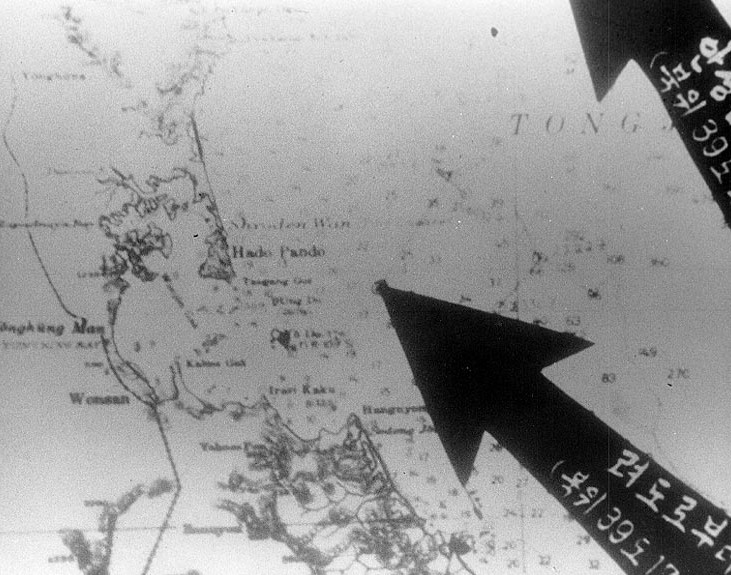

However, Pueblo never got the warning from NAVSECGRU, the organization in the U.S. Navy that handled the acquisition of intelligence. Even though the ship didn’t technically enter North Korean territorial waters, this didn’t matter to the authorities who promptly intercepted it in a heavy sub-chaser type SO-1, sending a signal demanding the vessel to come to a full stop.

Pueblo answered that they were rightfully in international waters, but they complied with the request. The SO-1 stood silent. Soon thereafter, four fast attack craft started circling around Pueblo. They were torpedo boats, and the next communication from the SO-1 ordered the U.S. vessel to follow the sub-chaser into North Korean waters.

Pueblo’s skipper, Commander Lloyd Bucher, quickly considered his options. To fight with half-frozen rifles against several ships which were at least twice as fast as his, had mounted deck guns, and which would surely be reinforced soon, would not be a wise course of action. He had only one viable option: try to flee and hold out just long enough for the American reinforcements to reach him.

Bucher ordered his men to begin destroying all classified material aboard the ship. He instructed the helmsman to change to a North-East course which would get the ship as far away from North Korea as possible. Unfortunately, not only were all of the enemies ships much faster, but two MIG jets flew overhead, eliminating any chance of slipping by.

It wasn’t long before the North Koreans grew tired of Bucher’s lack of compliance and opened fire with their machine guns and their 57mm deck cannons as well. They pumped Pueblo full of holes, but no shot was aimed below the waterline, an intentional move to keep the ship afloat. They meant business, and they intended to capture that ship.

As the minutes ticked past, several emergency messages were sent from Pueblo yet neither help nor a response from friendlies arrived. Inside the ship, the intelligence crew was hastily destroying the listening equipment with hammers, while burning and shredding all documents. Bucher signaled to the enemy ships that he would yield, but when he was ordered to follow the SO-1 at full speed, he told them that the ship had sustained engine damage. He ordered his helmsman not to exceed 5 knots, hoping to buy enough time for the documents to be destroyed.

But as the ship slowly approached the North Korean Wonsan port, it became clear that plenty of documents would still remain. NAVSECGRU had erroneously thought that the North Koreans wouldn’t dare intercept an American ship in international waters, so Pueblo was loaded with them. The whole crew of 83 men and their ship would be captured, and many details of their real mission would be known.

The men were taken to a building they later nicknamed “the barn,” where they were told to sign a document and make a public statement about being U.S. spies. They were told that if they didn’t comply, they would be executed. The U.S. Military Code of Conduct states that when captured, in no way should a servicemember make written statements disloyal or harmful to their country.

But that is a difficult instruction for a captain to follow when the enemy threatens to execute every crewman before him, one by one in a line, until he signed the statement. Understandably, Bucher yielded and signed.

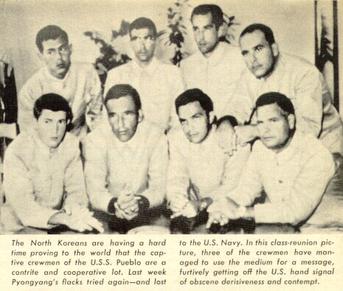

This seemed to appease the North Koreans a little, who now told the crew that instead of execution, they would face a long imprisonment until the U.S. cared enough to negotiate their release. The next thing they did was to take out a group photograph of the sailors who signed it for authenticity. That’s where the slick sailors pulled a fast one on their captors.

Having always been a hermit nation, North Korea’s isolation prevented their people from knowing the most basic cultural things about the U.S. and most of the world. The sailors realized that their captors didn’t know what it meant when someone gave them the middle finger, so they exploited it. They told them that it was a Hawaiian “good luck” gesture, so the North Koreans let them use it in all the pictures they took.

Whole months passed by before the North Koreans came to understand what the gesture really meant. But when they did, they turned cruel. The cells didn’t have bathrooms inside them and the sailors who just wanted to go to the common bathroom were beaten regularly either for “not holding it enough” or for “messing up their cell” when they decided to relieve themselves in there.

The crew’s food got worse, as if that were possible, and they now found their meals full of bugs. They were often forced to exercise to the point of exhaustion. Even at night they weren’t safe, as they were not only forced to sleep with their lights on but were also awoken regularly by loud noises. All the while, surveillance was constant. Every once in a while, mock executions were made.

Setting aside Kim Jong-Il’s anti-American propaganda, it was easy to understand where this excess hatred came from. The United States had killed almost a third of the North Korean population during the war that had ended in 1953, and there was not a soul in that country who had not lost a relative in that war. Still, these prisoners were treated like animals for almost a year.

A U.S. congressional investigation that was conducted long after the sailors’ release found that no real effort had been made to support Pueblo during the incident. This was because an aircraft raid against attacking North Korean forces would have certainly started another war. A whole task force approaching North Korea’s waters would have prompted the Soviets to intervene, making the Cold War turn hot all of a sudden.

After the ship’s capture, no rescue attempt was made because the North Koreans kept executioners on call inside the prison facility, meaning that no commando team could have arrived in time to prevent a tragic ending. So President Johnson kept on negotiating until it was agreed that the U.S. government would sign an official apology drafted by the North Koreans. On December 24, 1968, the sailors finally were flown back to the U.S.

After the ship’s capture, no rescue attempt was made because the North Koreans kept executioners on call inside the prison facility, meaning that no commando team could have arrived in time to prevent a tragic ending. So President Johnson kept on negotiating until it was agreed that the U.S. government would sign an official apology drafted by the North Koreans. On December 24, 1968, the sailors finally were flown back to the U.S.

The ship itself was never returned. It is still in commission by the U.S., but it is currently moored in Pyongyang, serving as a floating museum and a testament to the time North Korea captured an American ship, which in itself must be a most effective form of propaganda.