A “Buddha” is an enlightened being – one who breathes wisdom, goodness, compassion, and mercy. A saint, to put it in Christian terms. In one corner of China, there lived a man some consider to be a Buddha; even though he was a Nazi.

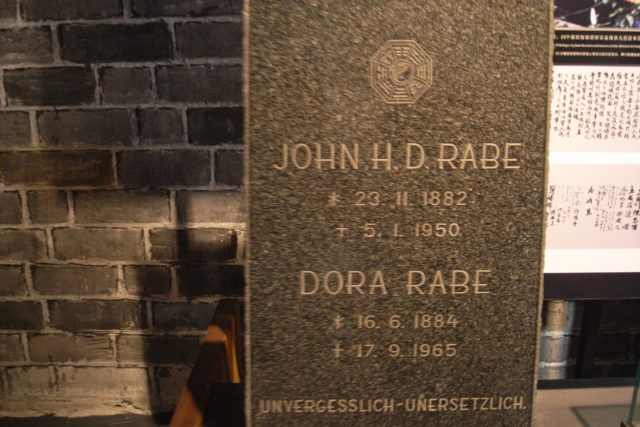

John Heinrich Detlev Rabe (pronounced RAH-bay, meaning “raven”) was born on November 23, 1882, in Hamburg, Germany. Due to his love of travel, he lived in Africa for several years doing odd jobs before being hired by Siemens AG.

In 1908, the company sent him to their offices in different Chinese cities where he worked his way up the corporate ladder. By the early 1930s, he was living in Nanking (now Nanjing) and was in charge of its local Siemens branch. His children and grandchildren were born in China.

Rabe became a Nazi and head of the local branch due to Nanking’s large German community. Horrific though that sounds, it would prove a blessing to many.

Japan had been whittling away at China since 1931, taking the entire region of Manchuria for themselves. As China was weak and Japan was still dependent on the West, both had been anxious to avoid a full-blown war. That changed when on August 13, 1937, Japan invaded the city of Shanghai.

Japan was confident of a quick victory, expecting to take the port city within days. The Chinese put up a fierce resistance, although it was futile. Shanghai fell on November 26.

China lost 250,000 soldiers and even more civilians (some of whom were foreigners) due to Japanese aerial bombardment of the city. Japan lost about 40,000 men.

The next city on their agenda was Nanking; then the capital of China. General Chiang Kai-shek (China’s leader) ordered the city to be held at all costs, but it did no good. Japanese planes bombarded it daily, while Japanese troops smashed through the Chinese forces trying to block their advance.

Many foreigners fled by way of the Yangtze River, as did wealthy Chinese residents – Chiang and his government, among them. Rabe ordered his family to leave.

He also kept a detailed diary of events, explaining why he had to stay:

“But there is one moral point I cannot get past. Our Chinese servants and employees all look up to their master. These poor, serving classes simply do not know what to do. Can I, have I, the right to run away under these circumstances? I think not.”

He, therefore, wrote to Hitler, pleading with the latter to intercede with the Japanese. On December 12, the last American embassy personnel boarded the gunboat Panay. Rabe also boarded to send a final plea to the Japanese government, again to no avail. Hours later, the ship was sunk by Japanese planes – killing three and wounding 48.

Rabe was busy with the International Committee – an ad hoc group of American and European businessmen, diplomatic personnel, teachers, and missionaries. Rabe and the IC had been working flat out since the fall of Shanghai to set up safe zones for the Chinese who could not get out.

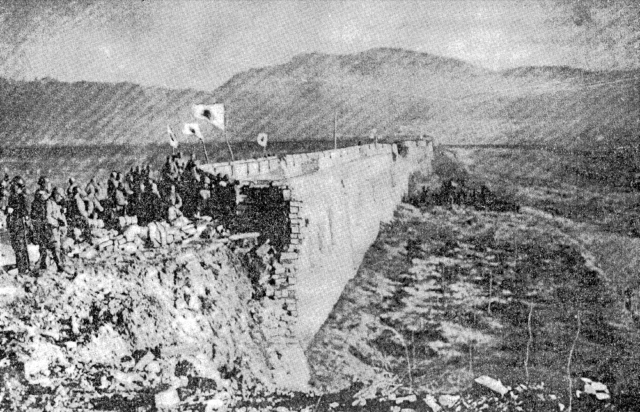

Nanking closed its gates. Chinese soldiers had to climb into the city by ropes lowered from the battlements. It did no good. Nanking fell on December 13. Japanese newspapers and film clips showed cheering masses and Japanese soldiers playing with Chinese children. It was a lie.

The rape and slaughter had begun. Despite continuing denials by the Japanese government today, people took pictures and movies in secret of what was happening. Among them was John Gillespie Magee – an American missionary whose photographs and films documented the hell Japan had brought.

In the midst of the horror, however, was the Nanking Safety Zone. It was made up of a series of neighborhoods surrounding Rabe’s house and was marked out by giant Nazi flags. He also opened his garden to shelter several families.

On the outskirts, however, things were different. Japanese soldiers frequently violated the perimeters of the Safety Zone. Rabe then brandished his swastika armband at them, and as Japan was allied with Germany, the soldiers had to relent.

For the next six weeks, Japanese soldiers went berserk. Chinese civilians within the city and the surrounding areas paid the price – about 300,000 were dead: men, women, and children. Within the Safety Zone, however, over 200,000 survived.

Before the invasion, the IC had worked to bring food, medicine, and other resources into the compound. On December 17, Rabe took one of his charges to hospital after she had been gang-raped and bayonetted in the face. The night before, he documented over 1,000 rapes at an all girls school run by missionaries.

After the Japanese left, Rabe returned to Germany in March 1938 to give talks about what happened – complete with pictures and film. He also asked for an audience with Hitler so the latter could bring the issue up with the Japanese government.

What he got, instead, was interrogated by the Gestapo. Afterward, he no longer spoke about Nanking. When WWII ended, he was arrested by the Allies for his party affiliation, lost his job, and ended up destitute. By the time the British deemed him de-Nazified in June 1946, he was suffering from malnutrition and a skin disease.

However, the survivors of Nanking had not forgotten. In 1948 they invited Rabe and his family to return to China so they could be taken care of, but Rabe was too sick to travel. Despite their own continued hardship, the city raised US$2,000 (roughly US$20,000 in 2017 values) and sent it to him, complete with food packages.

Those parcels continued every month for the Rabe family until October 1, 1949, when the communists took over. Rabe died the following year.

In 2005, Nanking converted his former house into the “John Rabe International Safety Zone Memorial Hall.”

Some declared him a modern Buddha.