None who survived the German concentration camps of WWII remember them fondly. Except for one man. As far as he was concerned, it is what helped him survive the Korean War.

Tibor “Ted” Rubin was born on June 18, 1929, in Pásztó, Hungary to a Jewish family. When WWII broke out, they tried to flee to Switzerland but failed.

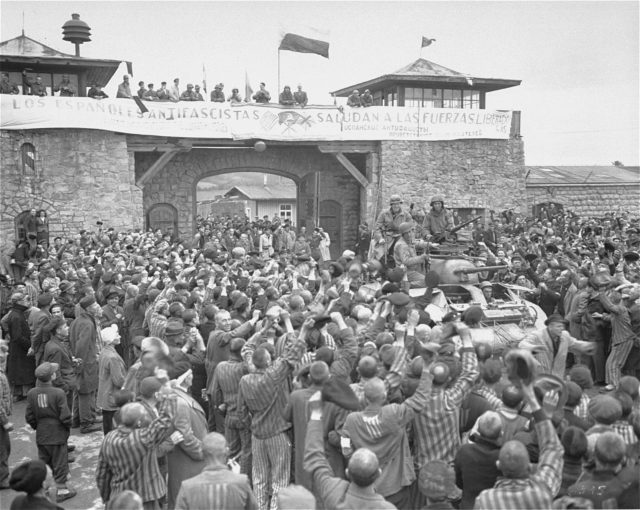

Thirteen-year-old Rubin was sent to the Mauthausen-Gusen complex, while the rest of his family were dispersed to other prisons where most died. After fourteen months of hell, he was liberated by the 11th Armored Division of General George Patton’s 3rd Army – an experience that defined the rest of his life.

Rubin never forgot how emaciated, diseased, filthy, and lice-ridden they had all been. Despite their condition, the Americans had no qualms about touching them and treating them with kindness. He, therefore, vowed to go to America and join the US Army to repay his debt to the country and to the GIs who had saved him.

He moved to New York in 1948. He enlisted the following year but failed the English language test. In 1950, with help from two other test takers, he made it. Unfortunately, it was not all as he had expected.

Although the US Army had liberated Jews in Europe, it suffered from virulent anti-Semitism within its ranks. Private First Class Rubin was assigned to I Company, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division under Sergeant Arthur Peyton; who always referred to him as “that f***ng Jew.”

After basic training, Rubin was sent to the 29th Infantry Regiment in Okinawa, Japan when the Korean War broke out.

Unhappy that Rubin had survived the Nazis, Peyton tried to rectify matters in Korea. Every time he needed someone for a dangerous mission, he sent for “that f***g Jew.” Whether it was to scout out an enemy position or to check out terrain suspected of having booby traps, Rubin was Peyton’s, go-to man.

To the sergeant’s annoyance, however, Rubin always came back with mission accomplished. Unfortunately for Rubin, Peyton was a very determined man.

Events came to a head on August 4, 1950. The North Koreans launched a major offensive, pushing the United Nations forces back – marking the start of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter. Several days later, his unit withdrew, and, Peyton “volunteered” Rubin to stay behind at a hill to guard the Taegu-Pusan Road link so more troops could retreat.

“We’ll come back for you,” were Peyton’s last words as he left Rubin alone.

At about 4 AM, Rubin heard gunfire from a large force making a beeline toward his position. He could have run, but his men depended on him, so he did the only thing he could.

He chucked a grenade from his foxhole. Scarcely had it exploded than he jumped in the next, chucked another, and then on to the next – continuously firing as he went. Although panicked and terrified, he was hoping the North Koreans would think there were many troops from different positions targeting them.

By dawn, silence fell. He waited for his unit to come for him, but by early afternoon, he realized the truth – Peyton would never send anyone to help him. He retreated to the Pusan Line when another realization hit – he had killed dozens of men he felt no hatred for.

Peyton was not happy to see him, but the rest of his unit were. Rubin had covered their retreat. Two of his commanding officers nominated him for a Medal of Honor (MoH). Unfortunately, they died shortly after but there were many witnesses to the recommendation.

On October 30, the 8th Cavalry was attacked by superior numbers at Unsan. Ordered to retreat ASAP and leave the wounded behind, Rubin refused. Despite his wounds, he tried to carry Corporal Leonard Hamm to safety, but they were heavily outnumbered by a joint Sino-North Korean force.

Rubin was sent to the Pukchin Mining POW Camp; better known to the Americans as “Death Valley.” When the Chinese discovered he was Hungarian, they repeatedly offered to send him back to Hungary as it was then part of the Soviet Union. Rubin refused.

He knew his only chance of survival was in wanting it badly enough, a lesson he had learned at Mauthausen. Not so the others who were losing their will to live from hunger, disease, and lice. He also said the Chinese were more humane than the Nazis, which was how many survived Death Valley.

When he could, Rubin stool food and medicine from the warehouses and gardens, risking torture or death. When he could not steal, he made soup from grass and knew the medicinal qualities of various weeds throughout the camp.

He encouraged the soldiers to stay as clean as they could by removing their lice. He carried men to the toilet if they were too weak to move. He was trying to remind them that they were still human and deserved some measure of dignity.

One man (later identified only as Johnny) was so ill he wanted to die. Rubin took goat poop and told him it was medicine. Johnny took it for several months while Rubin did everything he could to keep him clean and raise his spirits. Many soldiers swore he kept them sane and gave them the will to live.

North Korea finally released its prisoners in 1953. Over forty soldiers credited their survival in Death Valley to Rubin. Although he had been recommended for a MoH, Peyton his sergeant never acted on it.

In 1993, the US Army officially “discovered” it had significantly discriminated against minorities when it came to awards. President George W. Bush finally gave Rubin the Medal of Honor he truly deserved in 2005.