War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Samuel B. Parker.

Few things are more inspiring or compelling than stories of courage in the face of certain defeat. And few things are more satisfying than witty replies and retorts served up by those with their backs to the wall.

History’s five best responses to military ultimatums contain all the audacity and the bravado that one could ask for.

5. General José de Palafox y Melci: “War and the knife!”

José de Palafox y Melci was born in Aragon and raised in the Aragonese court. He began service in the guards during Napoleon’s military pursuit of world domination. After a brief period of retirement in Spain, Palafox was elected Duke Governor of Zaragoza upon his return in 1808.

The dawn of the 19th century witnessed the rise of France as a world superpower. Under the control and jurisdiction of Napoleon Bonaparte, the French empire attained and achieved status that the state had not seen since the days of Charlemagne. Among Palafox’s first decisions as Duke of Zaragoza was an immediate declaration of war against Napoleon and the French. Shortly thereafter, he began to produce and stockpile weapons, recruited thousands of troops, and took up a defensible position in the fortress of Zaragoza.

Napoleon’s quest for empire ultimately claimed a huge chunk of Western Europe. By early 1809, the French had already overrun and captured the majority of Spanish territories in an ongoing conflict which was to become known as the Peninsular War. Palafox and his men stood no chance against the might of France’s “Little Corporal”.

A French envoy offered Palafox fairly agreeable terms, suggesting “Peace and surrender”. Palafox came back with an offer of his own, promising the enemy diplomats “War and the knife!”

Palafox, in spite of facing superior numbers and firepower, elected to hold his position in the antiquated and poorly-manned fortress. This resolution ultimately resulted in a resounding and costly defeat and with the Spanish cessation of the city of Zaragoza. All told, some 50,000 French and Spanish troops and civilians perished in the Battle of Zaragoza, and Palafox himself was eventually captured by French forces.

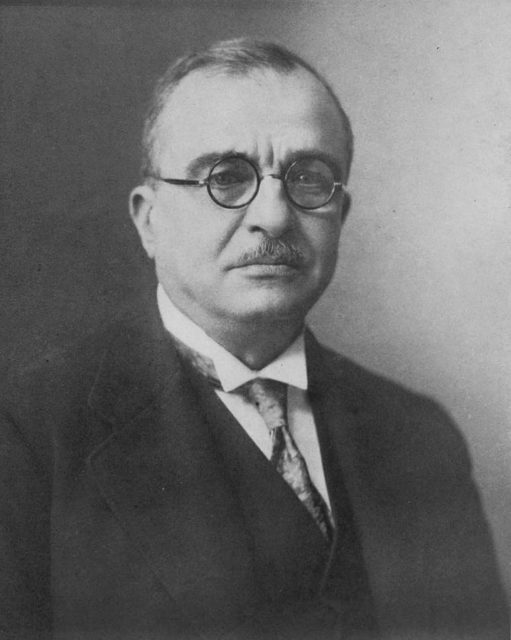

4. Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas: “No.”

Ioannis Metaxas remains a controversial figure in Greek political history, as his tenure as Prime Minister of Greece is marred with authoritarianism and elements of fascist, strongman regime building. A former soldier, Metaxas was elected in 1936 and served the first four months of his term in accordance with Greek Constitutional law. His compliance with legislation and legal precedent previously in place did not last long, however, and he began to abuse his power as he observed the rise of fascism in both Italy and Germany. And yet his most famous moment occurred towards the very end of his career, during the early years of World War II.

As the German Wehrmacht lightning attack raced across Europe, it soon became clear that the Nazi war machine was unstoppable. The Allies had already yielded Luxembourg, France, Holland, and most of Belgium by the time Italian forces under the command of Benito Mussolini, ally of the German state, arrived on the doorstep of Greece.

On October 28, 1940, Italian ambassador to Greece Emanuele Grazzi demanded unconditional Greek surrender and total cooperation with Axis occupation. Metaxas said quite simply: “No.”

In retaliation to Metaxas’ resistance, Italian forces attacked and crossed the Greek border, thus initiating the Greco-Italian War and beginning Greece’s brief participation in World War II. That same day, Greek citizens poured into the streets, proclaiming “Ohi!”, or “No!”, in open defiance of the Italian invasion. The Battle of Greece ended on April 30th, 1941, with a decisive Axis victory hallmarked by the capture of Athens on April 27th.

Some reports indicate that Metaxas actually replied to the ultimatum by asserting “Then it is war!”, rather than the conventionally celebrated account. Tradition, however, holds that Metaxas gave a resounding one-word answer, and October 28th is observed in Greece to this day as Epeteios tou “‘Ohi”; that is, “No” Day.

3. The Spartans: “Come and take them!”, “If…”

The Greco-Persian Wars were ultimately little more than a grudge match between the ancient confederation of Greek city states and kings of the Persian Empire: Xerxes the Great and his subsequent successor, Artaxerxes I.

After the Greek victory at the Battle of Marathon delayed Persia’s efforts of conquest and brought the First Greco-Persian War to a close, the Persian army returned with a vengeance in late August of 480 B.C. Vowing to overthrow and destroy Greece for its participation in and support of the Ionian revolt several years prior, King Xerxes I of Persia amassed an immense invasion force; while the exact size of the force remains unknown, “Father of History” Herodotus asserted that it was the largest to have ever walked the earth.

In an attempt to halt the Persian advance, a small coalition of Spartan soldiers gathered in the narrow coastal path of Thermopylae, Greece. The Greeks were astronomically outnumbered by what is widely considered to be the largest invading force of its day, with renowned Herodotus estimating the might of the Persian army to measure well over one million men.

When ordered to lay down their weapons by the Persian generals, the Spartans rejoindered “Come and take them!”

In an incredible display of valor and tenacity, the miniscule contingent of 300 Spartan troops staved off the massive Persian advance for over three days, buying time for the Greek army, and resisting and refusing to surrender until they were surrounded, cut off, and destroyed to the last man. A commemorative epitaph engraved on a plaque marks the spot where the last of the Spartans perished; it reads “Go tell the Spartans, thou who passest by, that here, obedient to their laws, we lie…”

Inspired by the courage of the Spartans, the Greeks united and successfully drove the Persians out of the nation, winning the second Greco-Persian War in one of the greatest military upsets of all time.

The Spartans arguably outdid themselves over a century later. As the Macedonian kingdom rose to power in the mid 300s B.C. under the command of Phillip II, predecessor of Alexander the Great, the Spartans again found themselves threatened and imposed upon by the expansion of empire. As Phillip II’s hoplite infantry approached the heavily defended city of Laconia, Macedonian delegates warned that, should the Laconians choose to resist, all inhabitants of the city would be slain if the Spartans were defeated. Spartan emissaries replied with a single word: “If….”

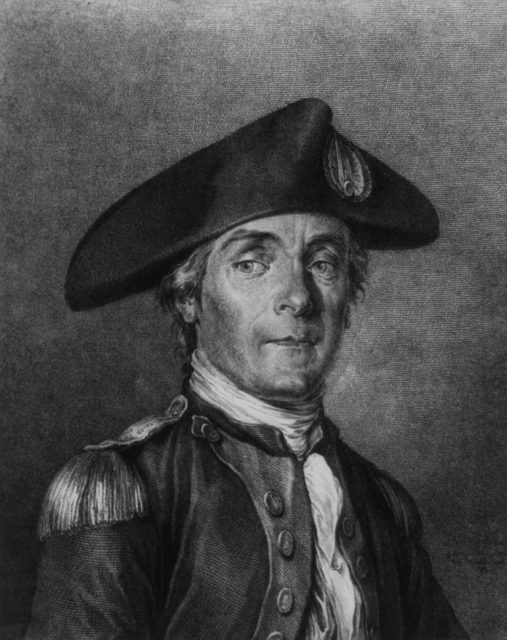

2. Commander John Paul Jones: “I have not yet begun to fight!”

John Paul Jones, often referred to as the “Father of the United States Navy”, is perhaps best remembered for his actions during a military altercation which occurred between the Continental Navy and the British Royal Navy during the American Revolutionary War.

Jones began his career at sea at the age of thirteen, serving with private merchants before volunteering with the Continental Navy in 1775. Jones distinguished himself in maritime military service and, as a result, was awarded command of the USS Bonhomme Richard, a rebuilt French merchant cargo ship gifted to the Continental Navy by Jacques Donatien LeRay.

On September 23rd, 1779, after sailing in the North Atlantic around the British Isles, Jones encountered the HMS Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough, escorts of the Baltic merchant fleet. In a seemingly suicidal maneuver, Jones brazenly engaged both vessels, and he soon sustained considerable injury to his ship.Upon being instructed to surrender by the captain of HMS Serapis, Jones countered, “I have not yet begun to fight!”

Mounting a furious three-hour counterattack from the listing and heavily damaged USS Bonhomme Richard, Jones, although heavily outnumbered and outgunned, defeated and captured both enemy crafts in an astounding victory. Jones stunned the British Navy by almost singlehandedly defeating and seizing two frigate escort ships. The USS Bonhomme Richard sank the following day, and Jones took command of the captured HMS Serapis.

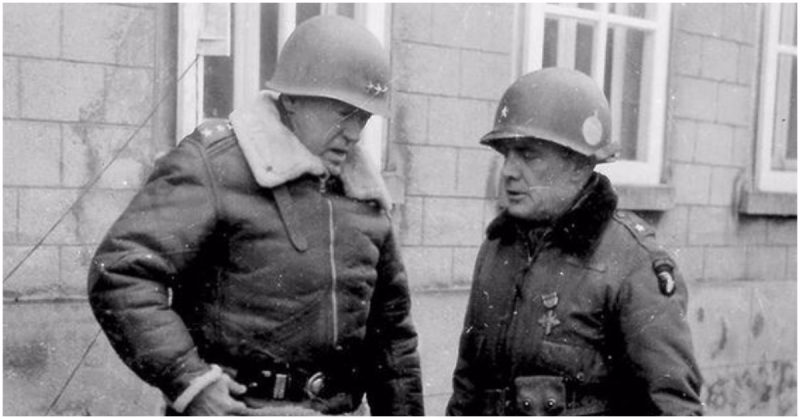

1. Brigadier General Anthony Clement McAuliffe: “Nuts”

During the winter of late 1944 and early 1945, Germany had begun losing the Western European front of World War II in earnest.

Having been slowly driven back across the Rhine River and into German territory since the D-Day Normandy landings of June 1944, the German armed forces attempted a final desperate push into Allied holdings, targeting Antwerp, Belgium, so as to prevent the Allied forces from utilizing the port city.

The Germans caught the unprepared Allied line off guard, swiftly and suddenly striking a concentrated and numerically inferior point of the American defense with almost half a million men and over a thousand tanks, initially pushing the coalition of American and British infantry forces into Belgium. The forced retreat was intended to split the Allied line, and caused a massive bulge in the defense, throwing the American forces into a state of disarray.

Brigadier General McAuliffe, commander of the U.S. 101st Airborne, withdrew as far as the crucial Belgian town of Bastogne. It was there, in the bitterly cold streets of the Belgian village, that the Brigadier General and his men determined to make a stand. Despite being surrounded by advancing German forces which outnumbered his own by a margin of 5 to 1, McAuliffe responded to German demands for surrender with a single word: “Nuts!”The 101st Airborne held Bastogne against all odds, managing to maintain their position in spite of being outmanned and outgunned until relief arrived in the form of General Patton and the U.S. 3rd army. Patton, famous for his intrepid campaigns, daring strategies, brash style, and brazen, audacious approach, rallied the American troops, and, in a brilliant counter thrust offensive, broke through the German line and pushed the German military back across the border. The Germans never recovered, and continued retreating back towards Berlin for the remainder of the war.