The April 24th Op is a major event in the history of the United States’ Special Forces operations not just because it was among the first missions of the Delta Force, but because its widespread failure would be a moment of profound humiliation for the United States.

Following the Iranian revolution, which saw the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and an end to his 22 years of autocratic leadership over Iran, the Iranian Hostage Crisis, on the 4th day of November 1979, ensued.

A group of militant students who supported the Iranian revolution had stormed the US embassy in Tehran, capturing the building and taking 52 American diplomats and citizens hostage for 444 days, in what would become the longest hostage crisis in history, and widely described by western media as an entanglement of vengeance and mutual incomprehension.

In the state-sanctioned act, the Iranian assailants demanded the return of Shah Reza, who had been taken to America for cancer treatment. Reza had been accused of committing crimes against the people and was summoned by Iran’s new leader, Ruholla Khomeini, to stand trial.

The hostage incident was initiated by Iran to spite America for her alleged complicity in Reza’s atrocities. Jimmy Carter was less than pleased by the event, and would succinctly declare that America would never yield to blackmail. The hostage-taking, to America, was an egregious violation of international law.

After 6 months of failed attempts at diplomatic negotiations, the United States, on April 16th, 1980, under President Jimmy Carter, approved a military action. The president, having broken diplomatic associations with Iran, ordered the Pentagon to draw up a plan in a bid to storm Iranian soil in a covert rescue mission codenamed Operation Eagle’s Claw.

The US military spent about 5 months in planning the op. The aircrew trained in Florida and Andersen Airfield in Guam. Based on the plan, 3 USAF MC-130 aircraft would fly an assault group of about 118 Delta Force soldiers from Masirah Island to a remote spot located 200 miles southeast of Tehran; this location was codenamed Desert One. The MC-130s were accompanied by 3 EC-130s which served as fuel transport.

Under the cover of night, 8 US Navy RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters, would fly from the USS Nimitz, which was sailing in the Arabian Sea, to rendezvous with the assault team where they would all fly to Desert Two, another location 65 miles from the target zone, Tehran.

Once the force was in place it would be show time; the team would be flown the rest of the way into Tehran where they would break into the embassy, neutralize the security, and rescue the hostages. All through the raid, an E-3 AWAC would keep a lookout on Iranian airspace, while establishing command and control communications between Washington, the Carrier Force, and the mission commander.

They would then fly to Manzarinyeh Air Base, which by that time would have been secured by US Army Rangers. At Manzarinyeh, USAF C-141 Starlifters would fly the hostages and assault team out of Iran, while the Rangers would stay behind to destroy all used equipment including the helicopters before flying out themselves.

This was an extremely complex plan that required a lot of synergy among all the units involved because Tehran was a city well inside Iran’s airspace and far away from any friendly territory. Furthermore, it was hard to get good intelligence about the forces inside the embassy. As a matter of fact, there was no room for any deviation from the stipulated plan as even the slightest mistake was bound to jeopardize the mission.

The first part of the mission went according to plan, with the arrival of the first MC-130 aircraft carrying Combat Control Team (CCT), mission equipment and fuel on board to Desert one. The team’s task at this point was to establish the airstrips and marshal the other aircraft when they arrived. But this was the only successful part of the mission because following the arrival of the other MC-130 aircraft, everything began to fall apart.

First, a passenger bus was spotted on a highway crossing the landing zone, and because this was supposed to be a covert op, the CCT was forced to stop and detain the passengers of the bus. A tanker truck was also found speeding close to Desert One. The truck, apparently smuggling fuel, was blown up after refusing to stop, causing the death of the passenger.

The rest of the C-130 aircraft arrived and waited for the helicopters. The RH-53 helicopters took off from Nimitz but along the way, one helicopter—Bluebeard 6—was grounded and abandoned. The crew reported a damaged rotor blade as the cause of the malfunction. The remaining helicopters ran into a severe sandstorm known as Haboob. This would scatter the flight formation, with Bluebeard 5 also abandoning the mission.

The scattered helicopters would arrive at Desert One individually, running 50-90 minutes behind schedule. Bluebeard 2 arrived last but had indications of a broken hydraulic system which consequently made it unfit for the mission. With just five helicopters left and even more losses anticipated, the on-scene commander, Col. James H. Kyle, requested a mission abort.

The new focus was now on getting the assault team back on the MC-130s while the Bluebeards refueled on the Nimitz. During this procedure, tragedy struck.

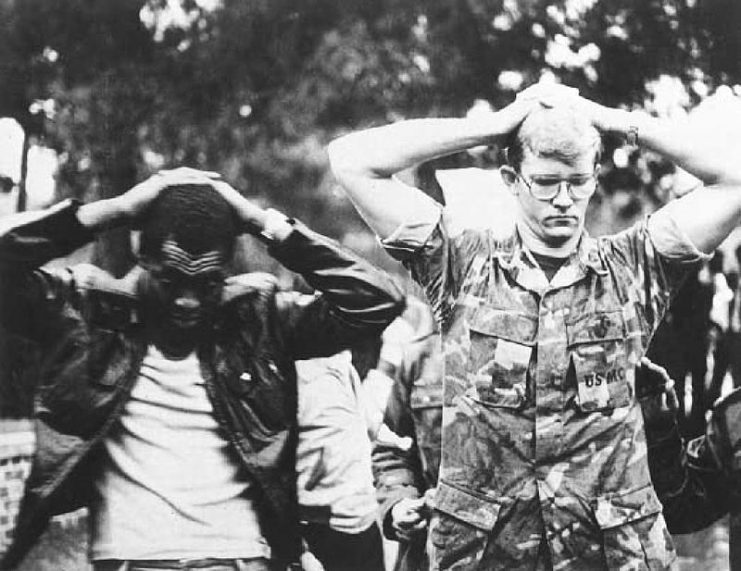

Bluebeard 3 was blasted by a desert storm, putting the pilot in a frenzied bid to maneuver his helicopter to stability. In the process, the helicopter’s main rotor blade collided with the wing-root of an EC-130 which was loaded with fuel. Both aircraft exploded, and in the ensuing inferno, 8 servicemen lost their lives – 3 US marines and 5 USAF aircrew.

The USAF pilot and co-pilot survived with severe burns. In the desperate evacuation of the rest of the team, classified files associated with the mission were burned, but the helicopters were abandoned in the desert. With that, Operation Eagle’s Claw, the nadir of the whole hostage rescue affair, came to an end.

The failed rescue op resulted in some rather undesirable consequences. Firstly, the hostages were scattered across Iran, to make another rescue mission impossible. Also, the US government received heavy criticism from governments around the world for making such blunders in a very critical situation. As a matter of fact, experts believe that Jimmy Carter’s failure with Operation Eagle Claw was a major reason he lost the presidential election the following year.

Additionally, the failure brought attention to deficiencies in the US special operations system. The Joint Chiefs of Staff led an investigation which birthed the Holloway Report. The report cited failings in mission planning, command and control, and inter-service operability.

It revealed that training was usually conducted in a compartmentalized manner, taking place in scattered locations. Also, there was poor selection and training of aircrew, and it was said that not enough helicopters were put into the mission to counter any unforeseen issues or problems that jeopardized the mission. The hopscotch method of ground refueling which was chosen over air refueling was also criticized.

In reaction to these findings, the US military established United Special Operations Command, and the Air Force Special Operations Command. The lessons learned prompted the creation of the Night Stalkers (the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment) for the training of Army pilots in low-level night flying and aerial refueling.

A second rescue operation was planned, but it was never implemented. However, on 20th January 1981, just after Carter’s tenure, all 52 hostages were allowed to go back home.

To America, Operation Eagle Claw was a profound humiliation which exposed their flaws and vulnerabilities. But to Khomeini and his people, it was a plan foiled by divine intervention.

Operation Eagle Claw was the mission that marked the beginning of a change in America’s Special Operations.