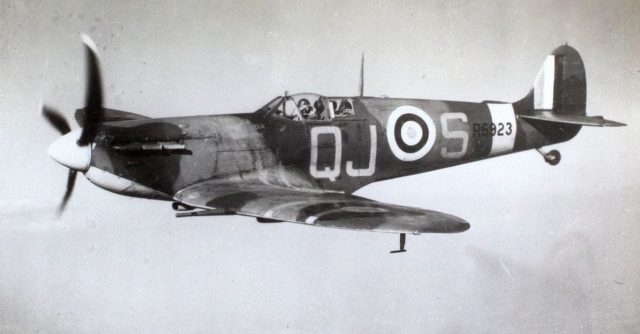

The Supermarine Spitfire was undoubtedly the most iconic British fighter plane of the Second World War. The name alone conjures up images of brutal dogfights over the English Channel during the battle of Britain.

One scenario involved a Spitfire protecting a helicopter carrying casualties from a jungle battle, all whilst a jet fighter fired rockets at communist insurgent positions in the jungles of the far east. This image would seem anachronistic at best, a ridiculous mash-up of WWII and the Vietnam War at worst.

However, this type of event would have been rather common during Operation Firedog, the British involvement in the Malayan Emergency from 1948-1960.

During the early years of the Cold War with all the changing technology, RAF Spitfires flew alongside jet fighters and early helicopters over the jungles of Malaya. Operation Firedog was the Royal Air Forces’ contribution to the conflict that became known as the Malayan Emergency.

Prelude to the Emergency

The British colonial control over Malaya had been fraught with difficulties long before the outbreak of hostilities in 1948. Taxation on major industries and the influx of Chinese migrants helped foment unrest among the population.

During the Second World War, the British government supplied and equipped Malayan insurgents to help resist the Japanese invasion (Jackson, 1991).

Following the end of the Second World War, most of the Malayan rebels laid down their arms and returned to their pre-war lives. However, the group that didn’t do so came to be known as Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA), a communist organization that had previously fought the Japanese.

The MRLA saw the social discontent that the war had produced as an opportunity to instigate a communist take-over of the country. As the conflict progressed, these insurgents became known as Communist Terrorists, or “CTs.”

The conflict began on July 16, 1948, when at 8:30 in the morning, three European officials were executed by Chinese members of the MRLA. A state of emergency was immediately declared (Van Tonder, 2017).

The RAF Response

The conflict in Malaya would become primarily an Army conflict involving ground forces engaged in jungle warfare. However, the British Royal Airforce (RAF) played a pivotal role in the conflict as well.

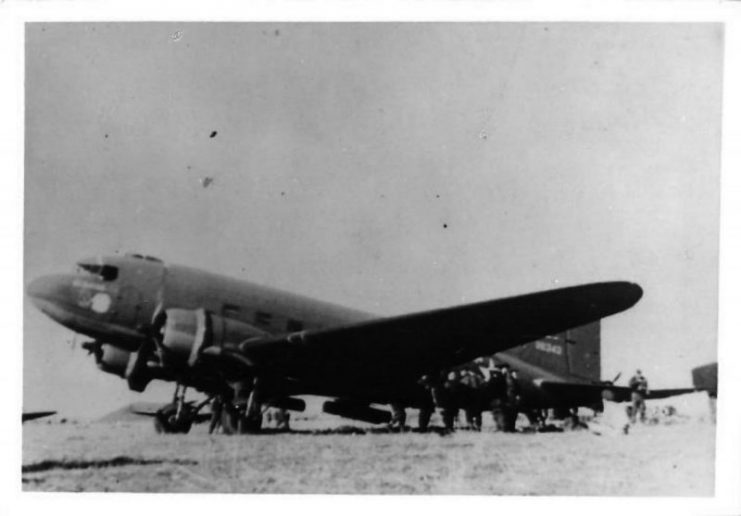

Following the declaration of the state of emergency, Spitfires, Dakotas, and later Bristol Beaufighters were dispatched to Kuala Lumpur to provide support for commonwealth forces engaged on the ground (Yao, 2016).

The first role these aircraft took on was photographic reconnaissance with the aim of supporting ground forces. The weather in the region proved to be hazardous to this project, but the intelligence proved invaluable, both for the military rooting out CT positions and for producing accurate maps of the region.

Another important role for the RAF was providing supplies for ground forces. As the conflict waged on, CT positions were pushed back further and further into the Malayan jungle. As a result, commonwealth troops needed supplies air-dropped to their positions while deep inside the jungle.

Such missions were made particularly difficult by the small size of the jungle clearings that the Dakotas were expected to airdrop supplies into, as well as the inhospitable weather conditions.

A true testament to the skill of the Dakota Pilots was that, at the beginning of 1949, the Dakotas were dropping on average 67 tons of supplies per month. By September, it had reached 84 tonnes. An impressive feat considering the conditions (Napier, 2018).

By 1949 the primary stroke aircraft used to carry out combat sorties on CT positions were the Beaufighter, Hawker Tempest (a mainstay of middle eastern operations at the time), and the Spitfire FR18. These aircraft were further augmented by the arrival of Avro Lincolns.

In the following three months, the RAF commenced a major offensive against the CTs in the region directly south-east of Kuala Lumpur. Between the 15th and 18th of April 1949, 97 sorties were flown against CT positions by a composite force comprising of Lincolns, Brigands, Tempests, and even Spitfires (Napier, 2018).

Many of the airstrikes against CT positions flown during this period were co-ordinated with army forces on the ground who could mark targets with colored smoke.

New Technology

By 1950, the intense jungle fighting on the ground compelled the RAF to establish a new unit to deal with the wounded. This became the RAF Casualty evacuation flight (later to become 194 Squadron). This flight was of interest due to the fact it was comprised of early helicopters, the Westland Dragonfly, that had been introduced in October 1948 (Rafmuseum.org.uk, 2018).

These helicopters were required to stay on a 2-hour standby so they could be airborne in much less time. After take-off, the CASEVAC helicopters would fly to the nearest Army landing strip from where they would carry out reconnaissance of the casualty’s location in order to determine the best location to set down and pick up the wounded.

The Dragonflies were routinely flown into small jungle clearings in which their rotor tips were only a few feet from the tree line.

In addition, the maximum vertical climb of the Dragonfly was only 130 feet (about 40 meters) when fully loaded with casualties. The fact that many of the CASEVAC’s took place in jungle terrain where the tree line was 70 feet (21 meters) higher than the helicopter’s maximum vertical climb height is a true testament to the skill and nerves of the pilots (Napier, 2018).

A further technological development during Operation Firedog was the introduction of de Havilland Vampires to 60 Squadron in 1950. These jet fighters first saw action in April of that year when they were cleared to attack a CT position. The Vampires fired unguided rocket-propelled explosives at their targets, destroying them outright.

It was during this period that the anachronisms of the conflict were most apparent. Spitfires were still being used to attack CT positions with machine guns, alongside jet-propelled aircraft firing rocket-propelled explosives.

This, coupled with the use of helicopters for CASEVAC purposes, led to an odd mishmash of technology that would seem quite bizarre to a modern observer.

Jungle Warfare

The Malayan conflict, as well as Operation Firedog, continued throughout the 1950s. New weapons and equipment entered service, and older ones were phased out. The Spitfire, the iconic British fighter plane, made its last combat sortie in January 1951 and was officially retired from service in 1954.

In October 1953, a heavy offensive took place in northern Malaya against CT positions. During the offensive, the RAF flew Lincolns, Hornets, Vampires, and Sunderlands against CT-held encampments in the Malayan jungles.

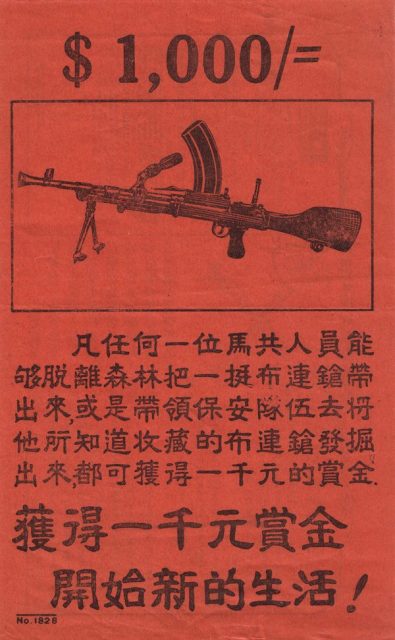

It was also during this month that the Lincolns dropped over 14 million leaflets, in multiple languages, imploring the CT fighters to surrender.

Helicopters also began to truly prove their worth to the RAF. The Dragonflies, and later the Sycamore HR14, had demonstrated their usefulness in the CASEVAC role.

Subsequently, the Whirlwind HAR4s were shown to be indispensable in moving troops into combat. The Whirlwinds were also used for inserting SAS teams into strategic locations in the jungle by parachute (Barber, 2004).

By 1955, the first jet bombers were being used in the conflict. The Canberra B6s were used to bomb CT encampments in northern Malaya, around the Kedah region. These aircraft were also used in Operation Unity which was the hunt for the communist party secretary-general, Chin Peng (Yao, 2016).

Operation Firedog continued to a lesser extent to the end of hostilities in 1960. Although the British far east forces played a decreasing role as the conflict continued later into the decade, RAF forces were present in the country up until the ceasefire was announced on July 12, 1960.

Read another story from us: 6 Hawker Fighter Planes that Took the RAF from Biplanes to Jets

The Malayan Emergency can be regarded as one of the few successful counterinsurgency operations of the Cold War (Nam.ac.uk, 2018). Operation Firedog was a pivotal point in the history of the Royal Air Force.

The weapons, equipment, and tactics used during the conflict in Malaya represent a bridge point between the RAF during the Second World War and the beginning of the Cold War.