Sabotage played a critical part in Allied operations in the Second World War. Such operations could significantly damage the enemy’s ability to get weapons, vehicles, and supplies to the front.

These daring missions could affect events hundreds of miles away, as happened with Operation Harling, an Anglo-Greek mission of 1942.

Cutting Rommel’s Supplies

From early in the Second World War, British forces fought the Axis armies in North Africa. By the autumn of 1942, they were on the offensive but faced fierce opposition from Field Marshal Rommel, one of Germany’s most gifted commanders.

One of Rommel’s biggest advantages was a steady supply line. This ran by rail from Germany across eastern Europe to Greece, from where it transferred to ships across the Mediterranean.

Forty-eight trains a day carried these supplies to their embarkation ports, delivering massive quantities of weapons and ammunition to Rommel. These supply trains relied on a single-line standard-gauge railway that ran through the Roumeli mountains in Central Greece.

Colin Gubbins, who was commanding operations for Britain’s Special Operations Executive, realized that this was the perfect place for irregular warfare, making it the weak link in the German supply chain.

By hitting the supply chain there, the British could significantly undermine Rommel’s efforts.

Into Greece

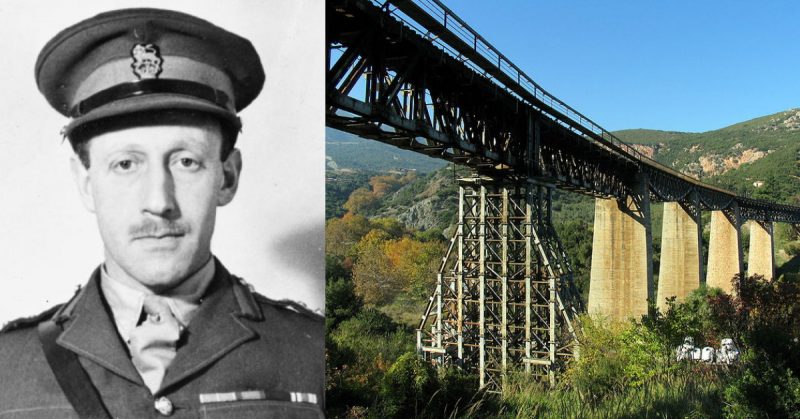

On the 30th of September, a twelve-man team of soldier saboteurs parachuted into Greece, led by Jewish sapper Eddie Myers. Most of them were British, though they included New Zealander Tom Barnes and Thermistocles Marinos, a Greek officer.

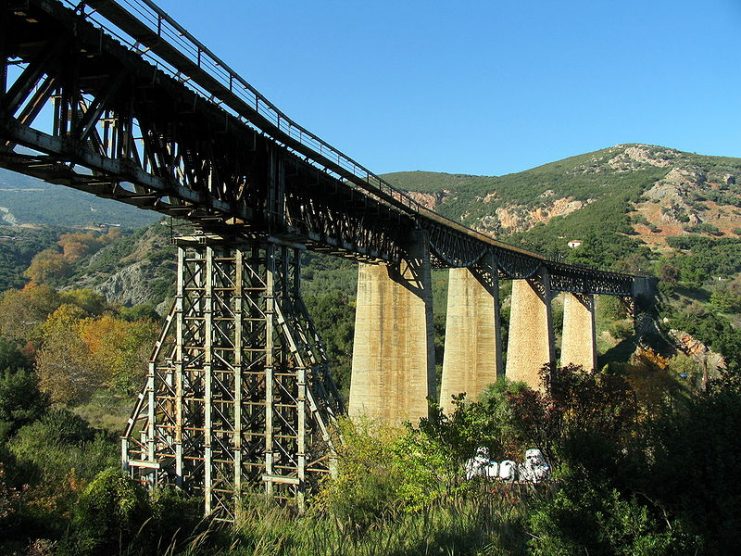

Their target was the Gorgopotamos viaduct, where the critical rail line crossed a gorge high in the mountains. If they could take out that viaduct, then they could cripple the rail line.

The saboteurs brought with them guns, knives, explosives, and other supplies. But their most important asset would be local help.

Meeting the Partisans

The team dropped in three groups, the members becoming scattered across the forested mountainsides.

Two of the groups quickly met up with sympathetic locals, who helped them find shelter, find each other, and hide out from Italian patrols. They also helped the soldiers retrieve their equipment drops.

In one alarming case, the soldiers had to stop children eating a package the kids had taken for fudge but which was actually plastic explosives.

Various bands of partisans were operating in the mountains, often in competition with each other. The teams were first introduced to a band of a hundred republican partisans led by Napoleon Zervas, who was delighted at the opportunity to work with the Allies.

Next, they made contact with the notoriously violent communists led by Aris Velouchiotis. Despite their political differences, Velouchiotis and Zeras agreed to work together with the teams against the Germans.

Velouchiotis also reunited the soldiers with the third group of agents, missing since the parachute drop, whom he had rescued from under the noses of an Italian garrison.

Preparing to Attack

While the forces were gathering, Myers scouted out the viaduct. He realized that the best way to destroy it would be by using explosives to cut through its steel girders – a challenging task.

More challenging still would be the approach. They couldn’t sabotage the bridge without taking out the sentries. Doing this would draw the attention of Italian garrisons at both ends of the bridge. For the mission to succeed, they would first have to take out those garrisons.

On the 23rd of November, they set out for the viaduct, trudging for hours through snow a foot deep. They reached points within striking distance of the Italians, where they spent the night.

The next day, mist prevented any action, but it cleared on the 25th, letting Myers complete his reconnaissance.

The attack was set for that night.

The Attack

few pics we could use in this paragraph – here. But not sure about copyrights

As dusk fell, the men advanced in columns down the mountainside. They divided into groups: two heading north and south to cover the rail lines, Tom Barnes leading a group down into the valley to blow the girders, and the rest assaulting the garrisons.

It was a moonlit night, light mist providing a little cover. The men crept close before launching the attack just after eleven.

At the south end of the bridge, things went well from the start. The attackers cleared Italian pillboxes using grenades, then assaulted the soldiers who remained. The surviving Italians quickly withdrew.

At the north end, the Italians put up stiffer resistance, driving back the initial assault. There was a fierce gunfight, in which it looked like the Italians would win.

Fortunately, Myers had held some men in reserve. He flung them into the northern attack. The fighting intensified, then suddenly went silent.

A flare went up. They had won. Both ends of the bridge were in Allied hands.

Sabotage!

Meanwhile, Barnes and his group climbed down the steep-sided gorge, accompanied by eight mules loaded with explosives. The crossed the wild river on a rickety plank bridge. Arriving at the target girders, they carefully placed their explosives.

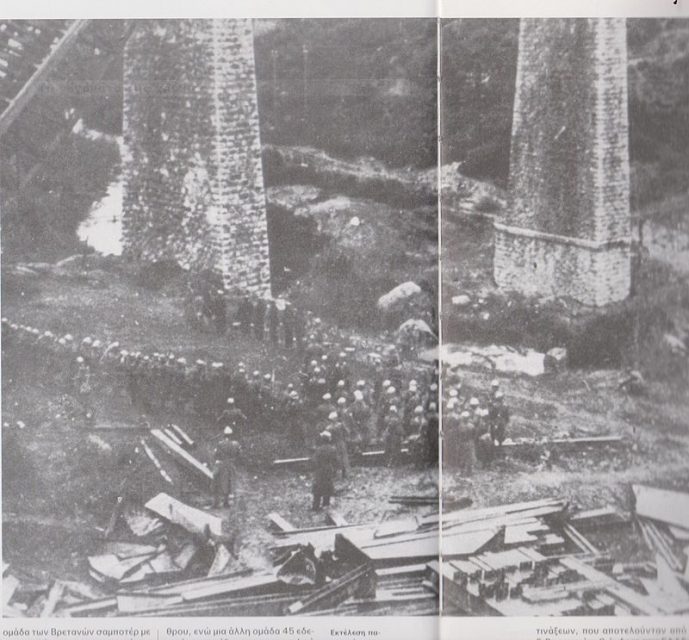

Barnes set the detonators then dived for cover, getting there just in time. A cataclysmic explosion rocked the valley, metal flying in every direction. Two huge spans came crashing down, severing the viaduct. A second batch of explosives mangled the remains.

With the mission complete, the attackers withdrew. They had suffered no deaths and only one man had been wounded. At least 30 Italian soldiers lay dead and the viaduct was in ruins.

Operation Harling was a complete success.

An Important Operation

It took six weeks for the Germans to rebuild the viaduct. This came at a crucial time, denting German supplies as American forces arrived to open up a new front.

Read another story from us: Axis Invasion of the Balkans and Crete with Photos

Just as importantly, Operation Harling had shown that Allied operatives and local partisans could collaborate to complete strategically important missions. It was a boost for the Greek resistance and a valuable precedent for future plans.

Instead of leaving Greece, Myers and his men remained. They formed a guerilla army thousands strong that continued smashing German supplies and harassing Italian troops.

The viaduct had been only the beginning.