Operation Meetinghouse- For the civilians of Tokyo who were caught in the bombing zone, it was as if hell had come to earth that night.

When thinking of the deadliest air raids in all of human history, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the Second World War are usually the first incidents that come to mind, or perhaps the firebombing of Dresden, which also took place during WWII.

However, one bombing raid stands head and shoulders above these in terms of sheer deadliness: the firebombing of Tokyo, conducted by the United States Army Air Forces in 1945.

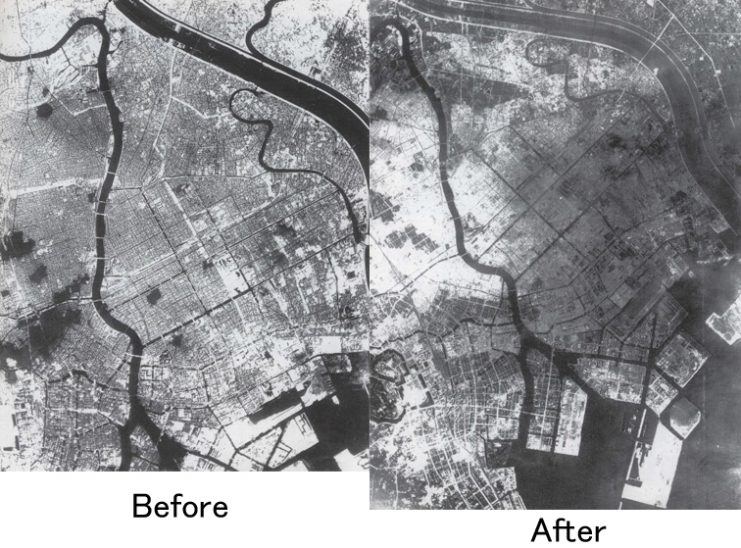

In the most devastating air raid in history, which took place over the course of the night of March 9-10, 1945, 100,000 people died and nearly a million were made homeless, while over 15 square miles of Tokyo city were reduced to rubble and ashes.

Operation Meetinghouse was part of a strategic campaign to severely disrupt Japan’s wartime production and destroy the morale of its people, so the bombing focused on the Shitamachi district of Tokyo, which was densely populated.

The bombs dropped there were not the standard explosive types used in many other bombing campaigns – these, instead, were incendiary bombs.

The 500-pound E-46 chemical incendiary bomb clusters, each containing thirty-eight M69 bomblets filled with napalm which was in turn ignited by white phosphorous, were devastatingly effective. When ignited, each M69 bomblet would shoot out flaming blobs of napalm up to a hundred feet away.

Wherever one of these blobs would land a fire would start, and in the 1940s Tokyo had a lot of wooden buildings and thatched roofs – perfect fuel for an inferno.

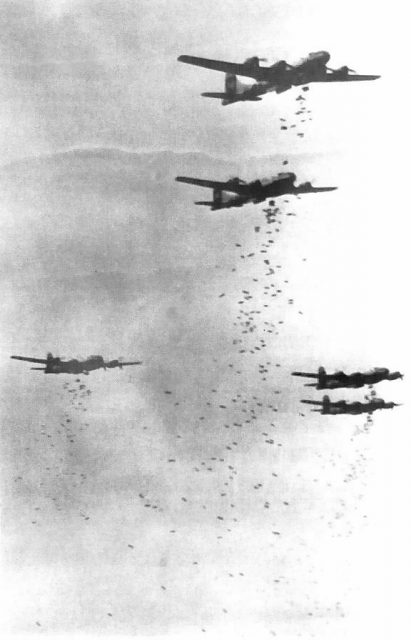

On the night of March 9, 1945, 334 B-29 bombers headed out to take part in the Operation Meetinghouse raid. Two hundred and seventy-nine of them ended up dropping 1,665 tons of bombs – mostly the aforementioned E-46 clusters – on Tokyo.

The burning napalm spat out by the thousands of bombs caused a conflagration that utterly consumed a large part of the city, and for the civilians who were caught in the bombing zone, it was as if hell had come to earth that night.

The wind that night, gusting at 28 mph, helped to spread the fires rapidly through the city and provided oxygen for the hungry flames. Small buildings were engulfed in minutes as the inferno tore through the city, and larger buildings came crashing down too.

Nothing was safe from the flames. In some places the heat from the massive fires was so intense that the water in the canals boiled, with temperatures on the ground getting as high as 1,800 degrees.

B-29 bombers continued to rain down incendiary bombs for a period of around three hours, and pilots and crew in some of the last planes to fly over the bombing zone could smell the horrific stench of charred human flesh wafting up in the towers of smoke rising from the burning city. As for those caught in the bombing zones, there was no escape.

Towering walls of flame, driven through the city blocks by the wind and abundance of flammable material, cut off any chance of flight from the terrible inferno. Tokyo’s firefighters were woefully underprepared for the intensity and extent of the blaze, and were all but powerless to combat it.

Some witnesses reported that the heat was so intense that people were bursting into flames before the fire reached them, and the towers of heat reached so high up into the sky that they were blowing B-29 bombers off course. Every living thing in the path of the wall of fire was reduced to ashes.

By morning the fires were out, but Tokyo had been hit hard. Estimates vary as to how many people died that night, but a safe and relatively conservative estimate is around 100,000. Over sixty percent of Tokyo’s commercial zones had been reduced to rubble, and nearly twenty percent of its industry had literally gone up in smoke.

Around 267,000 buildings had been destroyed, and around a million inhabitants of the city were now homeless, and had lost virtually everything in the inferno.

Blackened people staggered in a daze of disbelief around the ashes of what had once been their homes, some with even the clothes they had been wearing mostly burned off their bodies, searching for anything that could be salvaged from their former lives. In most cases there was nothing.

Read another story from us: Lucky or Unlucky? The Man Who Lived Through Two Atomic Bombs

While this devastatingly destructive bombing raid did not result in Japan’s immediate surrender – that would take another six months, and another two bombs, the likes of which the world had never seen, dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – Operation Meetinghouse did signal the beginning of the end for Japan.

Emperor Hirohito toured the parts of Tokyo that had been destroyed by Meetinghouse, and upon witnessing the terrible destruction that had been unleashed on his people, realized at that moment that Japan would have to start thinking about negotiating a surrender.