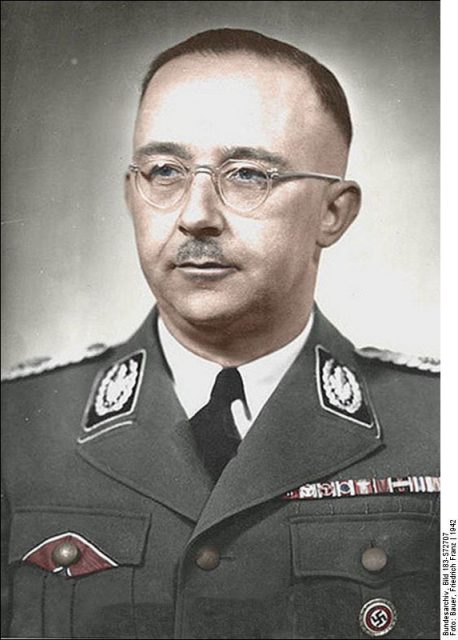

He built the notorious Schutzstaffel (SS) from a battalion of a mere 290 men into a paramilitary group of over a million, established himself as the facilitator of the Holocaust, and became one of the preeminent men of the Third Reich.

But with the war coming to an end, a desire for redemption brought him to a place where he had to do exactly what his position dictated that he shouldn’t: defy Hitler. It cost him much more than he was ready to pay.

With the ultimate failure of the lethal German offensive in the Ardennes, the war’s end had just begun, with Hitler stuck on the losing side. With the reality of his looming end haunting him on all sides, Hitler’s goal remained unshaken. He gave the order for the commencement of the Final Solution, which was to end in the complete extermination of Jews across Europe.

Nevertheless, Heinrich Himmler, the Plenipotentiary General of Hitler’s administration who was also in charge of prisoners of war and the concentration camps, was set to go on a path which he hoped would lead to his own welfare after the war.

Clearly aware that Nazi Germany had lost the war, Himmler had begun independent negotiations with the Allies, without Hitler’s consent, in hopes of obtaining some post-war security for himself and his comrades.

It was obvious that Hitler and all participants in the Holocaust would face the ugly wrath of justice by the end of the war, but Himmler believed that he had a very tiny chance of being treated more favorably by the Allies if he agreed to their demands: he was to put an end to all death marches, gassings, and massacres.

Himmler, known among the Nazis as the der treue Heinrich—”the faithful Heinrich”—was himself the horrific architect of the Holocaust. This fact made his unauthorized move toward uncertain favor quite a bold one.

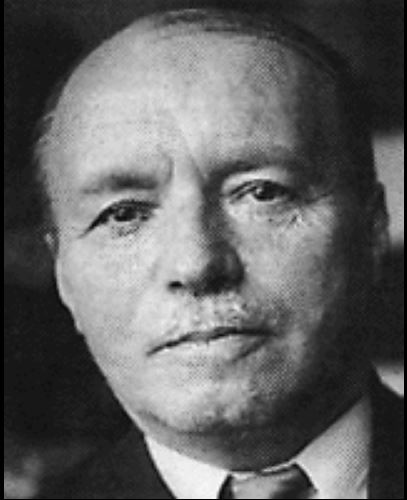

What moment set him on that track? One day, a former Nazi loyalist and longtime friend of Himmler’s, Dr. Jean-Marie Musy, had taken a seat beside him on a train headed from Breslau to Vienna.

And in the length of that journey, there had been a moment of thorough convincing. It ended with Himmler agreeing to end all the killings of the Jews, disregarding the standing order from Hitler.

By the end of November 1944, Himmler had ordered a cessation of the killings of Jewish prisoners all over the German realm.

He also ordered the destruction of all the gas chambers in the Auschwitz concentration camps, and gave the green light to the movement of Jews from concentration camps to Switzerland.

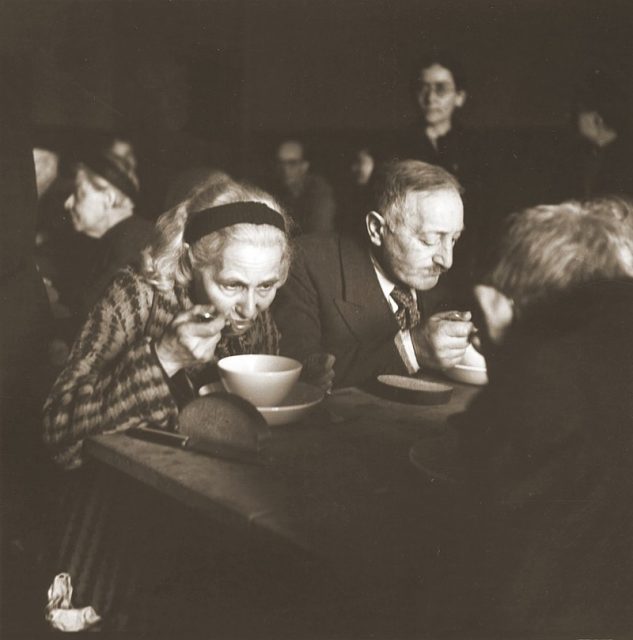

The first batch of captives, numbering about 1,200 Jews, was moved by train out of the Theresienstadt concentration camp. However, just after the success of this one transfer, Hitler discovered what Himmler was doing.

Himmler’s relationship with Hitler had, prior to that moment, been in a bad state after Hitler ordered him to step down as commander of the Upper Rhine Command and the Army Group Vistula due to failure. However, Hitler had always thought of Himmler as a very loyal subject and was particularly unprepared for his betrayal.

When he heard that Himmler had ordered the transfer of trainloads of Jews, Hitler issued a counter-command, ordering the transfers to stop.

Having made only one transfer and now unable to continue, Himmler switched to another plan. He began to put a stop on the death marches around the Reich and made efforts at safeguarding all the camps marked for destruction.

He was able to save only some of the camps, but the rest of the camps still met their tragic fate. By saving those camps, however, Himmler still managed to save several thousands of Jewish prisoners from immediate death.

Hitler’s rage vented itself upon Himmler: in a testament written before his suicide, Hitler declared Himmler a traitor, accused him of treachery, expelled him from the Nazi Party, and nullified all party and state offices held by Himmler.

Himmler faced rejection from his comrades for what they considered his self-motivated actions and disloyalty to the Fuhrer.

Meanwhile, the Allies had begun a hunt for Himmler, forcing him into hiding. A group of former Soviet POWs apprehended him at Bremervorde on 21 May 1945 and handed him over to the British.

It was apparent that the political concession, which Himmler sought from the Allies in what he had done, was not forthcoming. Two days later, while in British custody, Himmler committed suicide by biting into a cyanide pill.

His action late in the war, which resulted in the sparing of several thousands of Jews, is something that is largely overlooked.

Indeed, saving those Jews did not make him a hero. Perhaps you do not get any accolades for putting out a fire you started.

Himmler was at the spearhead of a historic genocide, and guilty of crimes against humanity. However, ignoring this story would most certainly be a snub towards the courage and bravery of people like Dr. Jean-Marie Musy, who did all they could to successfully convince a hardened Nazi loyalist to alter a course of action which would have led to the complete annihilation of all Jewish prisoners across Europe.

It is interesting to note the chain of events and meetings which ultimately led to Musy’s reunion with Himmler.

According to one Israeli newspaper, it all began with Dr. Reuben Hecht, who was a representative of the Jewish organization Irgun. While functioning as an Irgun representative in Zurich, Hecht grew to have a close relationship with Samuel Edison Woods, the American consul general in Zurich, and won him over to Zionism.

Through Woods, Hecht met with the Orthodox Jewish couple Yitzchak and Recha Sternbuch, who oversaw the Emergency Rescue Committee of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis in Switzerland. They connected with the Papal Nuncio to Switzerland, and slowly worked their influence across the Swiss diplomatic community.

By September 1944, they had effectively connected with Jean-Marie Musy, a former Nazi loyalist who had a relationship with Himmler. They successfully convinced Musy to embrace Zionism, and thus began a mission that turned Himmler into the exact opposite of what he was–and ultimately save the lives of several thousands of Jews.