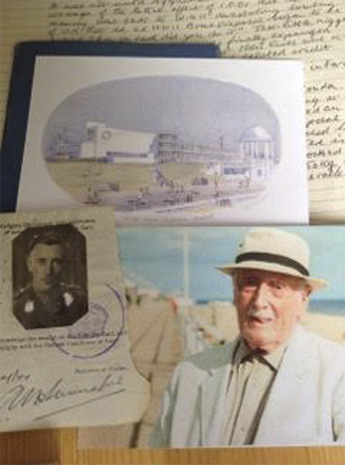

A chance finding of a watercolor painting in a charity shop in Bexhill On Sea began a journey for former Head Teach Pat Strickson, leading to the discovery of the remarkable and heroic acts by the artist AFJ Hannaford and his colleagues.

Pat Strickson enthusiastically pieced together his life story in a book and was gripped by coincidences, stirred by the passionate heartache present in his many notes, also heard in his conversations filmed for a Channel 4 documentary and an interview for the Imperial War Museum.

The research Pat did lead to a discovery of dark and dangerous times. Brave men blown up doing their job. It unearthed the secrecy surrounding their acts of courage and the often untimely end of their young lives from booby-trapped enemy bombs and, tragically, from our own mine clearance.

Captain John Hannaford, Royal Engineer Bomb Disposal Officer WWII, was a leader of men at 24.

He was told he would have only 10 weeks life expectancy in that job. But he died on Armistice Day, 2015, at the age of 98. He was one of the last surviving officers, never forgetting, still hearing the voices of those young men from the Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal, 8 Section 16 Company, blown up on a beach in South Wales.

The author hopes that this record will show that the officers and men who died should receive the recognition for their bravery and sacrifice, that John so longed for.

“Time Stood Still In A Muddy Hole: Captain John Hannaford – One of the last Bomb Disposal Officers of WWII” by Pat Strickson

Excerpt from the book

Chapter 111: Growing up

John’s association with bombs started early in WWI, not many months after his birth.

One evening after he’d been taken to visit his grandmother in London, his mother was pushing him in his pram along the Embankment. It was a warm summer’s night in early September 1917. His mother looked up and saw some planes. The late evening walk to settle him had the opposite effect. Night bombings were unheard of at the time.

The planes that came overhead were the first aerial bombardment in the heart of the capital. At first no one realised what was about to occur. In fact the crowds along the Thames stared skyward, wondering what was happening. The searchlights picked up the planes, then someone shouted to run for cover.

There was panic. People ran to get cover under bridges and hide wherever they could. There was confusion and disbelief followed by great explosions and people screaming and acrid smoke filling the air. Baby John would surely have cried as his mother dashed with him to safety.

The bombs were aiming for Charing Cross station, but missed. A tram was hit, killing the conductor and two passengers, and leaving a huge hole in the road, exposing the underground railway below. The bomb, which exploded nearest to them scattered shrapnel into the statue of the Sphinx, narrowly missing them and Cleopatra’s Needle.

You can still see the pockmarks to this day splattered over the plinth of the Sphinx with holes ripped into the metal paws of the great beast. In his interview for the Imperial War Museum John would wryly recall this early link and narrow escape.

In 2008 John wrote: ‘Unbelievably saw for the first time an aerial photo from a German bomber in 2017 dropping bombs on London. One clearly on the Embankment and confirmed the story my mother that we, with me in the pram, were very close to that bomb.’

Chapter 5: Ten Weeks and Ticking

Those first teams carried a minimal amount of equipment in a truck with 50 bags to fill for sandbags. They were to put the sandbags under the bombs and blow it up where it landed. But that wasn’t always the best plan, so that’s when the expertise of the first BD officers was used to defuze the bombs before they were taken away to blow up. The fuze was taken out, as once that happened the explosives in the bomb were inert.

Read another story from us: Heroic Bomb Disposal Expert of the Second World War

Sometimes if they couldn’t get to the fuze or it was jammed, they removed the explosives from the end of the bomb. Each time they started a new job they were fully aware that it could be their last.