Spending the latter years of the Great Depression serving in the U.S. Navy, Fred Hoechst Jr. returned to St. Louis following his discharge in March of 1940 to embark upon life as a civilian.

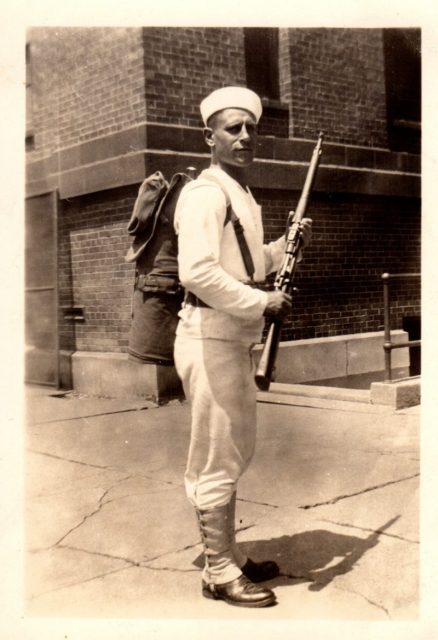

Although the previous four years had granted him a worldwide adventure aboard the battleship USS Colorado, little did Hoechst realize he would again don a sailor’s uniform after the country was drawn into war.

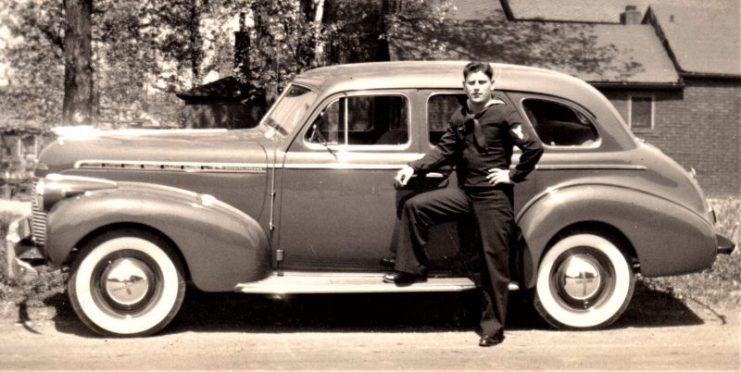

In the months after leaving the service, the veteran began working for Laclede Gas and used some of the money he saved to purchase a 1940 Chevrolet.

The following year he and his fiancée, Ruth Gieson, were married before a justice of the peace in Imperial, Missouri on February 19, 1941. Weeks later, he went to work for the National Lead Company in south St. Louis.

“The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands on December 7, 1941 marked the official entrance of the United States into World War II,” noted the Atomic Heritage Foundation. “The attack caught American military personnel by surprise and was certainly costly, but it did not cripple the U.S. Navy as the Japanese had anticipated.”

Hoechst was caught up in the patriotic furor gripping the nation and made the decision to return to the U.S. Navy to apply his peacetime naval skills in potential combat. Enlisting on March 25, 1942, he was assigned to the engine room of a ship that would enter service several weeks later—the USS Meade (DD-602).

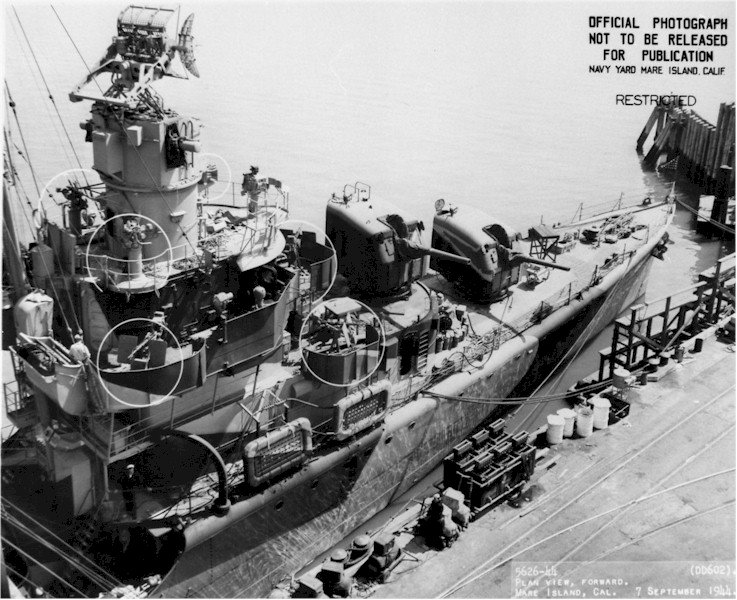

A Benson-class destroyer with a complement of 208 sailors, Meade was commissioned on June 22, 1942 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. According to a keepsake book given to members of the crew after the war, the ship “then had a shakedown cruise to Guantanamo Bay until 22 August.”

With the war fully underway, the book goes on to explain that there was little delay in deploying Meade afterward. The ship soon passed through the Panama Canal and “reported for duty to the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet on 28 August (1942).”

Hoechst ascended the enlisted ranks, eventually becoming one of only fourteen chief petty officers assigned to the ship.

In the early weeks after their arrival in the Pacific, he and his fellow sailors kept the engines in optimal condition through the Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942, during which Meade destroyed four Japanese transports and rescued 285 American sailors whose ships were sunk.

“A rapid change in locale followed,” explained a small pamphlet maintained by Hoechst after the war. “After a brief period in Sydney, Australia, the Meade steamed to the Aleutian Islands to participate in the bombardment and occupation of Kiska and Attu. Finally in September 1943, a respite from duty was given the ship with a short overhaul on the West Coast.”

Naval records reveal that the Meade received only a momentary break from the action as she again sailed for the South Pacific, arriving in Wellington, New Zealand on October 29, 1943.

The ship escorted U.S. Marines of the V Amphibious Force to the Battle of Tarawa the following month and again engaged in shore bombardments.

Danger abounded for the crew when contact with a submarine “was made on 22 November,” noted the souvenir booklet printed for sailors of the Meade. “With the assistance of the USS Frazier the sub was brought to the surface with depth charges, shelled and sunk,” resulting in the capture of one Japanese sailor.

Meade then sailed for Pearl Harbor to prepare for a return to the West Coast to undergo a major overhaul, but was rerouted to provide close fire support for the Battle of Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands in early 1944.

Throughout the next several weeks, Hoechst and the crew of the Meade became part of Task Force 58 and were engaged in attacks against Pacific locations such as Palau, Yap, Hollandia, Truk and Ponape (Pohnpei). They were detached from the task force in April 1944 and began patrolling islands controlled by the Japanese.

“During a shore bombardment ‘practice’ on Milli [Atoll], the Meade came the closest in her Pacific career to being hit,” recorded the Meade souvenir booklet. “The [Japanese] returned fire for the first time. However, no damage or casualties were received.”

The closing of Hoechst’s combat service approached when Meade received orders to report to the West Coast for a much needed overhaul in July 1944. Months later, they completed a shakedown and were sent to provide shore fire support during the liberation of the Philippines in the waning weeks of the war.

The Japanese surrendered on September 2, 1945, and Hoechst received his discharge the following month on October 25, 1945. During his naval career, he completed nearly 7.5 years of active service and earned an at Asiic-Pacific Campaign Medal with 9 stars, which represented his participation in 9 campaigns of the war.

After coming home to St. Louis, Hoechst returned to the National Lead Company, from which he would retire decades later. He and his wife raised one son, Jerry, and in their retirement years enjoyed bowling and traveling. Upon his passing in 1995, he was laid to rest in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

A famed painter once explained that men like Hoechst were a dedicated type of individual. Through his actions, he demonstrated that sailors and those who embraced a life on the sea possessed a uniquely brave perspective. Despite being faced with the hardships of a life on the water, they never made excuses to avoid embarking upon a nautical journey.

Read another story from us: PART 1 – The search for Amelia – Missouri veteran served aboard ship that searched for famed 1930s aviator

“The fishermen know that the sea is dangerous and the storm terrible,” wrote the late Vincent Van Gogh, “but they have never found these dangers sufficient reason for remaining ashore.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.