This is Part 2 of a three-part series about the Japanese midget submarine attack on Pearl Harbor during World War II. Part 1 gives an overview of the submarines and their mission, Part 2 discusses their actions and the American reactions during the attack, and Part 3 describes the misadventures of the submarine officer who became America’s first Japanese POW, as well as where each midget sub was found in later years. Click here for Part 1.

Submarines Sighted

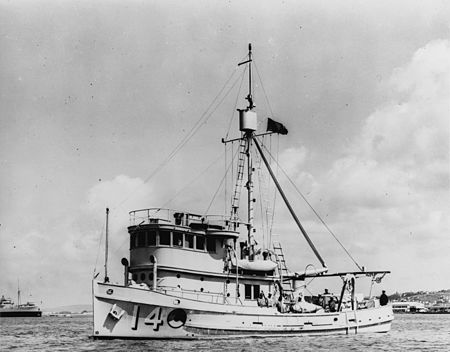

Despite the cover of darkness, the Americans detected two of the midget submarines before they reached the harbor entrance. Ensign McCloy, officer of the deck on the minesweeper USS Condor (AMc-14), spotted the first one at 3:42 AM when he noticed something unusual splashing through the water outside the harbor entrance.

Condor‘s quartermaster identified the strange object, saying, “That’s a periscope, sir, and there aren’t supposed to be any subs in that area.” Condor used her signal blinker to inform USS Ward (DD-139), the destroyer on duty in the Defensive Sea Area, that she had seen a submarine.

Lieutenant Outerbridge, who had taken command of Ward only two days previously, immediately sounded General Quarters. The destroyer searched the area for over half an hour, but found nothing. Outerbridge figured that since Condor did not report the sighting, the minesweeper’s crew was not positive it was a submarine. Neither ship reported the incident to headquarters at Pearl Harbor.

The second midget was seen at about 6:30, when Commander Grannis of the supply ship USS Antares (AKS-3) noticed a suspicious object “about 1,500 yards on starboard quarter” following his ship toward the harbor entrance. Grannis promptly radioed Ward.

The message was received on Ward by Ensign Goepner, who figured the object was just a buoy but told Quartermaster Gearin to “keep an eye on it.” Gearin watched it awhile, then concluded, “Sir, it looks like a small conning tower, and I’ve never seen a buoy move at five knots through the water.”

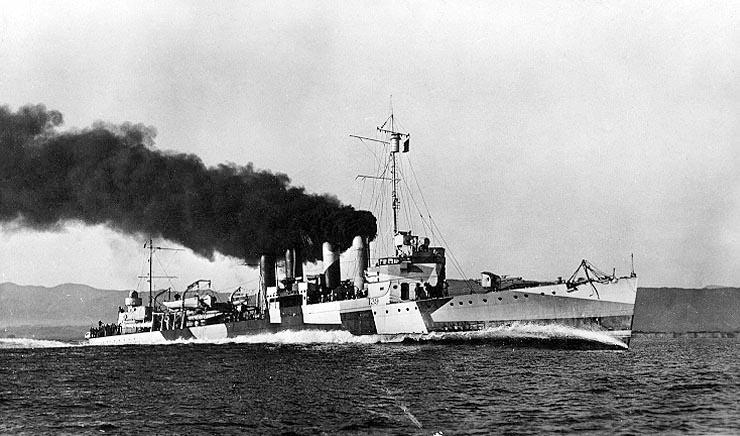

They woke up Outerbridge, who came on deck, looked at the object, and immediately thought “She is going to follow the Antares in, whatever it is.” Convinced that the object “couldn’t be anything else” but a submarine, Outerbridge fell back on his orders to fire on unidentified, unescorted submarines trespassing in the Defensive Sea Area.

General Quarters sounded for the second time that morning, and Ward‘s sailors manned their battle stations again. This time they got some definite action.

One Midget Down

The submarine apparently never saw the destroyer coming, and Ward was only fifty yards away when her first shot went just over the conning tower and splashed into the sea. The second shot solidly hit the conning tower. As the submarine slowed and began to sink, Ward destroyed it with depth charges.

Outerbridge sent two messages to headquarters. Thinking the short first message might be interpreted as a false alarm, he elaborated in the second one, “We have attacked, fired upon, and dropped depth charges upon submarine operating in Defensive Sea Area.” Shortly afterward Ward depth-charged another contact, though without conclusive results, and reported that incident as well.

Upon receiving Ward‘s various radio messages sometime after 7:00, the commanders at Pearl Harbor were taken aback by the destroyer’s reports. They began to take routine measures to counter a submarine threat, such as ordering USS Monaghan (DD-354), the ready-duty destroyer inside the harbor, to join Ward at sea. After much discussion they decided to “obtain a verification of the Ward‘s report” before taking further action.

They were still waiting at 7:55 when the Japanese air strike began. Fortunately for the Japanese pilots, the Americans had failed to realize that the submarine incident had given them advance notice of an impending larger attack. However, it did warn the Americans that submarines were lurking outside the harbor, so the mother submarines lost the chance for their own surprise attack upon any ships leaving the harbor.

Midget in the Harbor

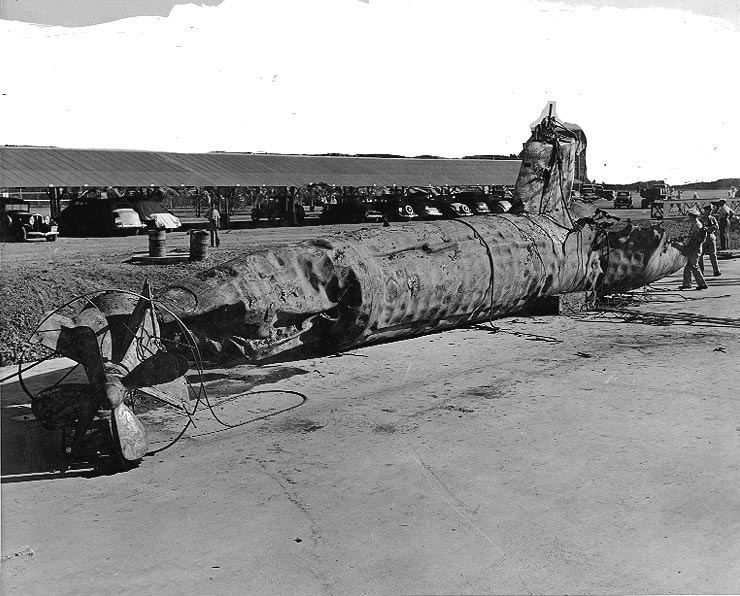

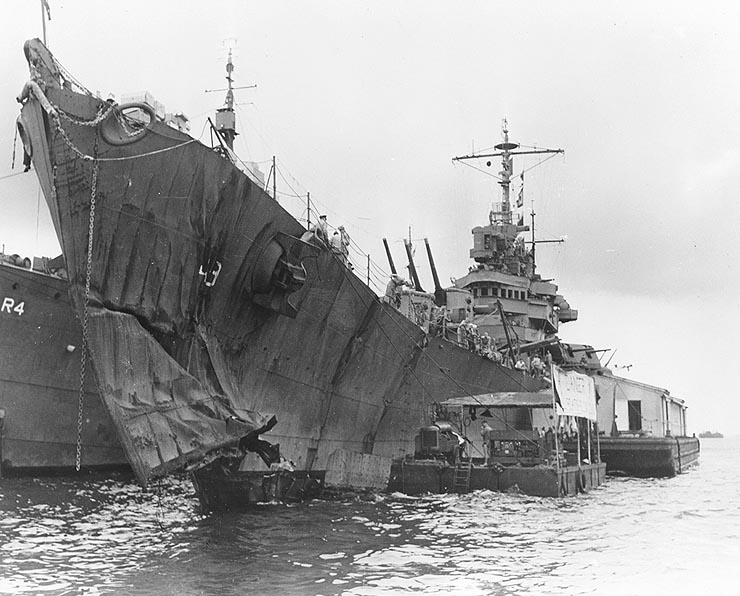

Only one midget submarine is certain to have actually entered Pearl Harbor. Despite reaching its destination, this midget failed to aid the air strike by sinking any ships—instead, it was chased down and destroyed.

The tugboat YT-153 spotted its periscope first and tried to run it over, but the midget managed to disappear unscathed into an area of cloudy water. Shortly thereafter, at 8:39, the seaplane tender USS Curtiss (AV-4) hoisted a signal flag to indicate that a submarine was inside the harbor.

“Curtiss must be crazy,” stated Commander Burford of Monaghan, which was then underway to join Ward. But after his signalman pointed out what looked like “an over and under shotgun barrel looking up” at him, Burford declared, “I don’t know what the hell it is, but it shouldn’t be there.”

As Monaghan began to charge the submarine, intent on ramming it, Curtiss scored a direct hit on the conning tower which decapitated the submarine’s captain. In a post-war interview with the historian Gordon Prange, Burford described the moments in which Monaghan and the submarine squared off.

One can imagine the pure chaos: the speeding ship, swarming aircraft, falling ordnance, explosions, billowing smoke, anti aircraft fire—including Monaghan‘s own guns—and the fact that the destroyer had to avoid crashing into other ships in restricted maneuvering space while dealing with this unforeseen complication. Burford concluded, “God—a lot was going on in just a few minutes of time.”

The midget submarine meanwhile had contributed to the general mayhem by firing both of its torpedoes, but missed its targets. The first torpedo hit a dock instead of Curtiss. The second missed the oncoming Monaghan by twenty yards and exploded on the bank of Ford Island.

Failing to directly ram the sub, Monaghan depth-charged it, totally destroying it at the danger of blowing off her own stern while nearby sailors cheered.

Meanwhile, Outside the Harbor…

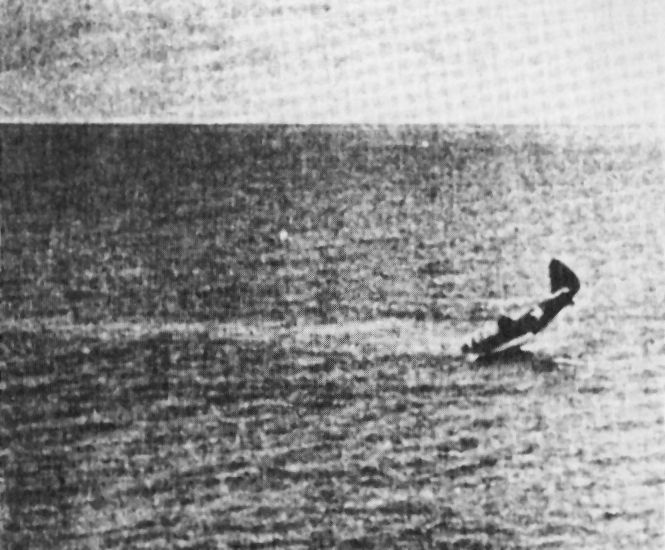

American contacts with Japanese submarines outside the harbor continued throughout the air attack, but none of the submarines succeeded in preventing any ships from leaving the harbor or sinking them in the open sea once they escaped. The closest call from a midget submarine attack came for the cruiser USS St. Louis (CL-49), the only large ship to leave the harbor during the attack.

As St. Louis proceeded down the channel at 10:04, Captain Rood saw two torpedoes coming directly at his ship. By some dangerous zig-zagging in the narrow channel, St. Louis managed to dodge them, and the torpedoes exploded on a nearby coral reef instead.

Having just lost (literally) a ton of weight, the midget submarine that had fired the torpedoes bobbed to the surface. The sailors on St. Louis fired at it and believed they had hit the conning tower, but it submerged and they were not positive it was an official kill.

As the second wave of attacking aircraft receded, the situation outside the harbor got livelier for any submarines unwary enough to come within reach of the vigilantly patrolling destroyers. At 9:26 American military officials had ordered, “Send all destroyers to sea and destroy enemy submarines.”

Read another story from us: Pearl Harbor: Massive Mission for Midget Submarines, Part 1

The destroyers spent such a busy day submarine hunting, blasting anything that seemed to be a contact, that some of them ran out of depth charges and had to go back to Pearl Harbor for more. If the third midget had survived any encounters with American ships earlier in the morning, it was likely damaged or sunk at this time.

The fourth midget submarine is accounted for until 12:41 AM on December 8, when Ensign Yokoyama radioed “Successful surprise attack” to the mother sub I-16. He was never heard from again.