A man in the midst of a mid-life crisis is not a pretty sight. His mood can trigger all kinds of ill-advised behavior and foolish deeds. A soldier in mid-life, with no war to occupy him, can be a dangerous and reckless man indeed.

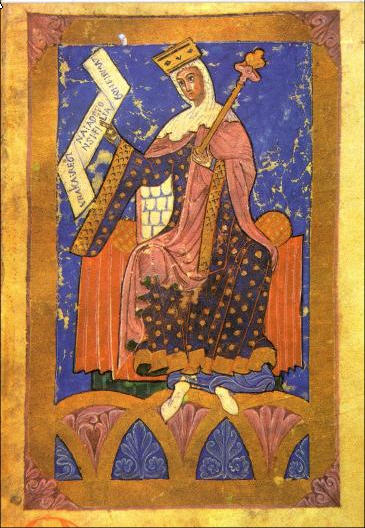

Pedro Gonzales de Lara was just such a man. He had once been the lover of Urraca, Queen of Spain around 1120 A.D. They had not married but only because her father said no.

Nevertheless, he had been her constant companion throughout her reign. When she died in 1126, he was left listless and unhappy.

Now that his queen was dead and his best battles, like the Siege of Antioch, were behind him, de Lara was unsure of his next move. During Urraca’s time, the country had enjoyed a relatively stable period, but now she was gone. He felt paralyzed without her.

If he couldn’t fight, what would he do?

To make matters worse, he felt middle age and its creeping infirmaries doing damage to his muscles and his eyesight.

After the queen’s death, skirmishes and revolts in some northern regions of the country seized on him as an ally and leader. But those in power quickly tamped down the unrest, and de Lara was sent into exile.

He had no endeavor once Urraca died, so he drifted, wondering what his next move should be. Then boredom really set in.

He attached himself to the King of Aragon, Alfonso I, nicknamed “the Battler” for his quarrelsome nature. Alfonso was fighting to recapture Spain from the Moors and was at war with the Duke of Aquitaine, who was holed up behind the walled city at Bayonne.

Alfonso successfully laid siege to Bayonne and planted himself and his men around the city to wait it out. Along with de Lara, he waited for reinforcements. Time passed and boredom quickly set in again.

Finally, the reinforcements came. Unfortunately for de Lara, they were led by a man with whom he shared many past grievances: the Count of Toulouse, Alfonso Jordan. De Lara loathed Jordan because he felt entitled to all Jordan had that he no longer did: power, wealth, influence.

De Lara was becoming a bitter, old man, and he knew it.

Just hearing Jordan’s name inspired jealousy and rage in de Lara. Jordan was a well-established nobleman, but de Lara was little more than a gun for hire, a man who sold his fighting skills to the highest bidder. Jordan had precipitously landed on the right side in a bid for power after the Queen’s death, but de Lara was nobody anymore.

To make matters worse, King Alfonso I held Jordan in high regard.

Jordan and his men arrived on the scene to provide the king and his men with some relief. But de Lara hated even the sight of him: his clothing, his countenance, his smug manner of speaking. De Lara could not contain his rage and he challenged Jordan to a jousting match, one-on-one.

Jordan did not deign to answer him, not directly. He had a lowly staff member turn to de Lara and accept. He had not even recognized de Lara from their shared days on the battlefield and at court. When pressed, he implied that he thought de Lara had died, either in battle or of old age.

This infuriated de Lara even more, who was determined to prove he had not lost his skills as a warrior.

In those days, jousting was not the glamorous endeavor depicted in paintings and movies. The men wore heavy chain mail, and the fights often went to the bitter end with one man left standing. Even the horses had it rough as they went in wearing no protection.

The men squared off, facing one another in a hurriedly constructed ring in which they could charge. Spectators gathered, even from the walled city of Bayonne. Everyone wanted to watch this bloody spectacle.

Someone blared a horn. They rushed straight at one another, swords held high.

In truth, de Lara didn’t stand a chance. He was getting old, thick around the middle, and weak. Jordan was young, strong, and prepared.

De Lara took the first blow hard, his shield breaking as he flew from his horse and broke an arm when he landed on the dusty, hard ground.

Jordan leaped from his horse and they faced off, ready for hand to hand combat. When de Lara lifted his sword, Jordan seized his chance. He stepped in toward an unprotected area of de Lara’s torso and jammed a long, slender blade deep into his chest. De Lara fell and could not get to his feet again.

Men carried de Lara away to the camp where a monk tended his wound for two days. It was a fruitless effort, and de Lara died in great pain over those long 48 hours.

This was an ignominious end to the life of a man who had once been a hugely powerful individual as the Queen’s consort. But when she died, the power de Lara thought was his died with her.

Read another story from us: Once the Greatest Army in Europe – The Black Army of Hungary

There is a lesson here: about the transient nature of power, about ego, and about men who cling to what is not rightfully theirs. De Lara could have lived out his life quietly in exile, but he could not adapt to the one thing that life demanded of him: anonymity.