War History Online presents this guest blog by Benjamin Phelps

Bain: Charles was more Extraordinary than Great

American historian Robert Nisbet Bain writes his biography, Charles XII and the Collapse of the Swedish Empire, (among the first written in English) to give an “adequate” description of Charles using the most “recent” research available. Bain’s purpose is to also, “dissipate the many erroneous notions concerning ‘The Lion of the North’ for which Voltaire’s brilliant and attractive work; I had almost said romance, Histoire de Charles XII is mainly responsible”.

One can be more trusting of Bain’s work than Voltaire’s, since Bain is not promoting any political ideology, but rather is solely interested in giving a truthful representation of events from the facts as he seems them. Bain uses original sources, but also relies heavily on Swedish biographies. He writes in an organized and chronological style which makes it easy for the reader to follow Bain’s thoughts.

Bain begins his work by giving a thorough background of the early life of Charles and what affected the shaping of his character. This is an area on which Voltaire did not dwell very much, and when he did, he often promoted false information. Bain understands that the upbringing of Charles XII should be the starting point for understanding his character. Bain believes that Charles’ father, Charles XI, had a profound influence on the way the younger Charles viewed the monarchy. Bain reports that Charles XI was up between three and four in the morning every day to begin cabinet work.

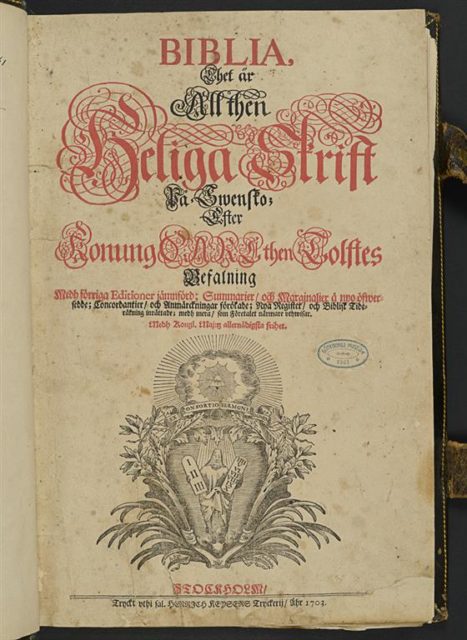

The life at the court in Stockholm was very unlike that of Versailles, “[Charles XI] despised the luxuries and the refinements of life and looked upon sloth and frivolity as unpardonable offences”. Charles XI’s religious life also provided much for the younger Charles to imitate, “[Charles XI] read a chapter in the Bible every morning and evening, took the sacrament very regularly and never without careful preparation”. These actions were backed with powerful words, “I am but a man and a sinner like other men and Almighty God is appeased not by high-sounding titles, but by the prayers of faithful and humble hearts” . By highlighting the religious life of Charles XI, Bain demonstrates that he understands the importance of one’s religion and how it molds one’s character; this is the exact opposite of Voltaire’s view.

Bain also focuses on Charles’ mother, Queen Ulrica Leonora, who wished to have her son to have a good Christian education. To illustrate this, Bain quotes a letter to Charles’ future tutor in which the Queen gives very Lutheran instructions,

The tutor must impress upon his pupil, on all occasions, that although he is a King’s son and the heir to a great realm, nevertheless he ought always humbly to reconise [sic] this as God’s special grace and favor and be diligent in acquiring those Christian virtues and necessary dispositions which can alone make him worthy of his high birth and fit for his high calling. The Prince must learn, betimes, to bear in mind that it is Almighty God alone who sets kings up and puts them down, and it is He who will, one day, demand a strict reckoning from all those who are born to crowns and scepters as to how they have made use of what has been placed in their hands, wherefore it becomes them especially to take heed lest they misuse the authority which God has given them to the oppression of others and their own destruction. (31)

Bain states that, contrary to the common opinion of many biographers, both Charles XI and Ulrica Leonora raised their son and paid great attention to his education and spiritual welfare. Others (including Voltaire) state that Charles XI did not have a large influence on Charles, and in ways which he did, it was only to ingrain the need to preserve the absolute monarchy. Bain states that Charles XII would have been benefited if his father had lived even a few years longer than he did, a sentiment not shared by Voltaire.

Bain, like Voltaire, is captivated by the personal bravery, courage and skill of Charles XII on the battlefield. Bain also notes that Charles had a loving attitude troops. Like Voltaire, Bain includes several anecdotes which he uses to show Charles as a caring leader. It was the personal touch, which gave Charles amazing powers as a leader. Bain states, “It is a fact that so long as he was able to mingle with his men, and lead them personally, they endured their torments without a murmur”.

While Bain is impressed by Charles as military leader, he finds Charles to be less than competent in the diplomatic arena. Bain records diplomatic “missed opportunities” with Prussia, Russia, the Ottoman Empire and others. Bain admits that Charles may have had good plans in the beginning but, “Unfortunately that obstinate tenacity with which Charles always clung to his pet projects long after the original conditions had changed and favorable opportunities had gone ruined everything”.

Bain is of the opinion that it was Charles’ refusal to make peace at a loss which led to the collapse of the Swedish Empire. This opinion is in agreement with that of Voltaire, but Bain gives no support for Voltaire’s view that Charles became an apathetic Lutheran later in life. What Voltaire describes as “absolute predestination,” Bain calls “fatalism” by which Bain claims that Charles, “tried to explain, to his own satisfaction, the undeserved failure of his righteous cause”. Why is his “righteous cause?” Voltaire and Bain make it clear that Charles was fighting only against those nations that attacked him, which they did solely out of greed for Swedish lands. This “fatalism” could very easily be considered in confidence and trust in God’s will, whatever the result. Bain quotes Charles writing to his sister, “And yet it becomes us to resign ourselves to the will of the Most High, and patiently endure the well-earned chastisement which it has pleased Him to lay upon us, for He has taught us that He lays no cross upon us so heavy that He Himself cannot help us to bear it” (311).

Hatton: Endurance, Loyalty and Responsibility

Ragnhild Marie Hatton, former Professor of International History at the University of London, identifies two schools of “Caroline” historians: the “old school,” critical historians, or the ambivalent, “new school”. Hatton states that Charles’ character is too complex for either one of these schools. Instead, she attempts to write an objective biography of Charles XII by using a large quantity and variety of original sources. Hatton provides fresh insights to the mindset of Charles and views events from the ground, instead of writing from the distance of hindsight as Voltaire and Bain are more prone to do.

Hatton takes a similar approach as Bain when she begins her work by describing the family and heritage of Charles XII. She gives many examples which support Bain concerning the character of Charles’ parents and their wish to give him a Christian education. This contrasts sharply with Voltaire who claims that Charles XI was nothing but a cold and cruel absolutist, whose ways drove his wife to an early death. While Bain refutes this, Hatton makes the truth even clearer. Charles XI deeply loved his wife and suffered from severe depression from the time of the death of his wife to his own. Indeed, Hatton gives only one real example of the royal couple arguing, and that was over how to care for the physical and moral well-being of their children (42).

Hatton’s research has also revealed another outstanding erroneous opinion of Voltaire. While Voltaire considered Charles to be nothing more than a brave warrior who was “unschooled,” Hatton demonstrates that the exact opposite was true. Apart from the “God-fearing spirit” which his parents saw as absolutely necessary, they also wished their son to have a well-rounded education of the mind, body and soul. He had a thorough Lutheran theological education under Bishop Erik Benzelius, learned riding and fencing, mathematics, engineering and was able to speak, read and write in Swedish, German, Latin and Greek. Hatton concludes that Charles’ education was, “to develop at an early age the Prince’s logical and analytical powers … [and] a code of morals which stressed the need for a king to love justice, to honor his word and to accept adversity as well as good fortune in a spirit of humility before God” (51).

Hatton, more than Bain and certainly more than Voltaire, gives a detailed look at the mindset of Charles XII and his views on war. She is able to this because she uses all sources available to her; this includes, among many other documents, numerous personal letters of the king and those close to him. Hatton strongly disagrees with Voltaire and other critics who claim that Charles was bent on conquest, “[Charles] had conceived ‘a perfect horror’ at the mere prospect of an aggressive war. To explain the Northern War, as has sometimes been done, as due to the ‘warlust’ of Charles XII and his desire to shine as commander seems therefore ill-founded” (111).

Concerning Charles’ personal faith, Hatton gives several examples of his “piety” (not in a Pietistic sense), including reports of his visitors while on campaign, “They noted the regularity with which he attended prayers and took part in the hymn-singing morning and night” (173). The king often made use of the phrase “With God’s help” so that it was also reported that, “no soldier draws his sword without first saying, ‘With God’s help’” (173). Hatton also notes that Charles possessed a great amount of self-confidence which verged on arrogance (173). However, Hatton believes that this was offset by Charles’ powerful work-ethic and his desire to visit all his soldiers (combined with his personal skill and bravery in battle), which made him immeasurably popular (173).

While these actions may be a very good indication of Charles’ character, Hatton gives even clearer insights into Charles personality. Hatton states that while the details of Charles’ devotional life are hard to find, it is known that he often prayed alone and that it gave him peace in his own mind (296). Hatton also states that Charles took preparation for communion very seriously. Like his father, he would examine himself carefully before taking it. He would even postpone it when he did not feel that he was properly prepared. Hatton cites one instance when he had had a serious argument with one of his ministers on the day he was to take the sacrament this caused Charles to postpone it until he had made peace (484). Charles continued to pray with regularity through his life, even after all seemed to turn against him; this strongly contradicts Voltaire’ notion that Charles became apathetic.

Hatton goes into greater detail than Bain concerning Charles religious beliefs apart from actions. Hatton records several different opinions of Charles’ contemporaries. Some believe that he became sympathetic to Islam when he was in the Ottoman Empire, others say he was later “indifferent to religion” while some Pietistic Swedish clergy claimed that he sympathized with their views. However, Hatton turns to those closest to Charles before she makes a conclusion.

Hatton looks at what Charles’ personal chaplains later wrote about him. Hatton finds that they, “were convinced that his personal devoutness persisted throughout his life and were at pains to refute accusations that the King became progressively ‘less religious’ as he got older” (431). Hatton concludes that Charles had, “more than a formal adherence to the faith in which the King had been brought up” (431). While Hatton and Bain both stand in opposition to Voltaire on this point, Hatton is more firm in her conclusion and has better support for her conclusion than Bain or Voltaire.

Hatton also disagrees with Bain and Voltaire when they suggest that Charles was foolish to avoid peace negotiations when he had the chance. Hatton states that, after careful examination of sources, it appears that Charles’ diplomacy was more complex and thoroughly planned than what was initially evident. For Hatton, it was not Charles’ death in battle that saved Sweden from a destructive war, but his death ended any real chance of victory (521).

Conclusion

The three authors whom this essay examined laid out three distinct views of Charles XII of Sweden. It seems that Voltaire was severely handicapped in his accuracy by the limited availability of sources, even though he considered himself fortunate in those which he had. He was limited in his objectivity by the recentness of events which still strongly pertained to the time in which he was writing as a philosopher. Bain, writing much later, had more access to sources than Voltaire. He left some important issues, but since he stated that his intention was only to give a biographical outline and writes objectively, he accomplishes his goal. Hatton uses many more sources than either Voltaire or Bain and writes a significantly more detailed, longer and thorough work. Her opinions carry the most weight and she, more than the others, properly identifies the importance of the affect Charles’ religious thinking on his character.

Author Benjamin Phelps

Bain, Robert Nisbet. Charles XII and the Collapse of the Swedish Empire. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1895.

Hatton, Ragnhild Marie. Charles XII of Sweden. New York: Weybright and Talley, 1968.

Voltaire. Lion of the North. Trans. M.F.O. Jenkins. East Brunswick: Associated University Presses, Inc., 1981.