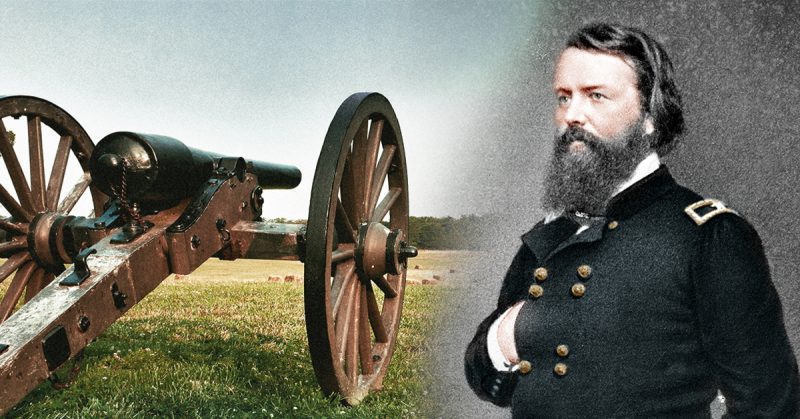

In late August 1862, thirteen months after the first Battle of Bull Run, the Union army was poised for a rematch against the Confederates in the Second Battle of Bull Run. As determined the Federals were not to lose a second time, however, they went up against an army that was just as eager to win.

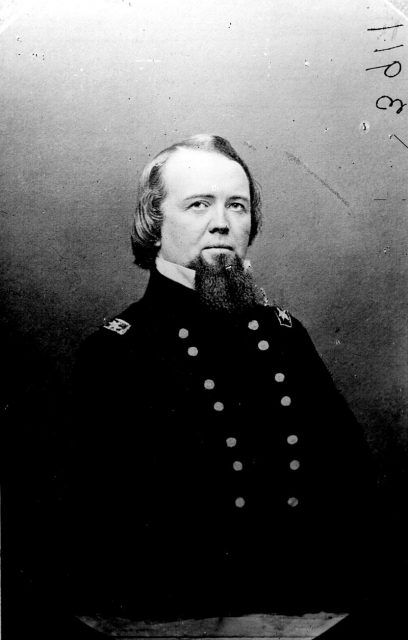

The battle resulted in 20,000 more Federal than Confederate casualties–and it was yet another defeat for the Federals. Many attribute the Confederate victory to the poor military strategy of the aggressive Union general, Major General John Pope.

Earlier, in June 1862, Lincoln had appointed Maj. Gen. Pope as the new commander of the Army of Virginia, and planned to merge the Army of the Potomac with the Army of Virginia. This combining of forces would enable a more threatening attack on the Confederate capital at Richmond. With Federal forces at well over 75,000 men, they fancied better odds against the 55,000 Confederates opposing them.

Confederate General Robert Lee got wind of this plan and he refused to grant the Union forces to have such an advantage in numbers, so he decided to attack Pope’s army before they could merge with the Army of the Potomac. General Lee split his forces and sent half under the command of the great General “Stonewall” Jackson to flank Pope’s army, while the other half would remain under Major General Longstreet’s command.

On August 27, Jackson’s forces had captured and destroyed the Union supply depot at Manassas Junction, hampering Pope’s ability to communicate with the Federal capital in Washington D.C. This attack also forced Pope to retreat from Rappahannock Station. However, when Pope’s forces circled back to confront Jackson’s men, they couldn’t locate them. Jackson’s forces had left the junction and taken a position on Stony Ridge to await Longstreet’s army.

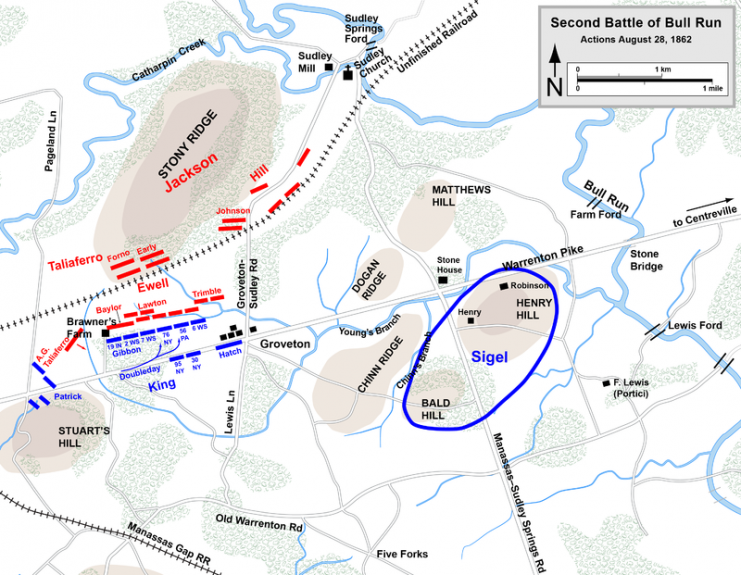

Thursday, August 28, 1862 was the auspicious day the second battle of Bull Run, also known as Second Manassas, began. Jackson’s forces attacked the Federals along the Warrenton turnpike just outside Gainesville, Virginia, near a farm belonging to John Brawner. General Jackson’s main intent was to take firm hold of Union General Pope’s forces, until Longstreet could arrive with the remainder of the Army of Northern Virginia.

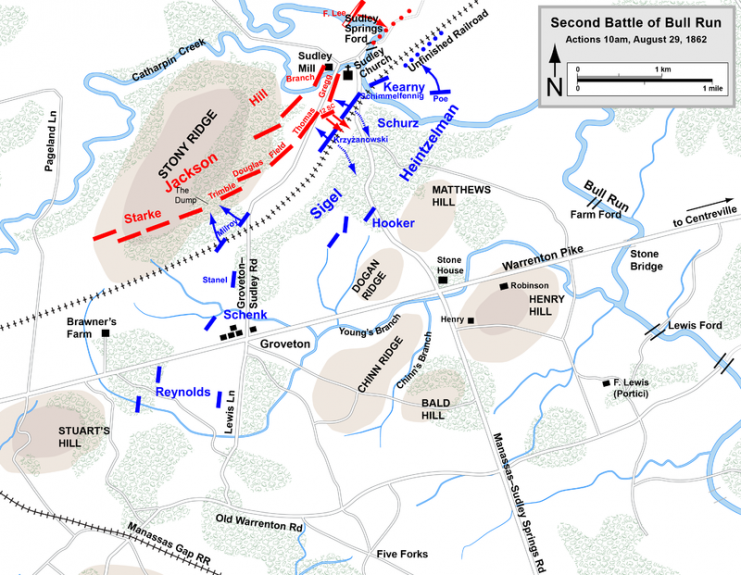

General Pope misjudged the situation, thinking that Jackson’s forces would retreat to join Longstreet’s advancing army, and tried to trap Jackson’s men. On the morning of August 29, Pope sent divisions to launch an attack on Jackson’s forces, but Jackson’s army was able to hold their positions–albeit not without a large number of casualties on both sides.

Meanwhile, General Longstreet’s army arrived by noon and took position on Jackson’s right flank. Although General Lee had suggested that Longstreet attack on the 29th, Longstreet refused, preferring to fight on the defensive.

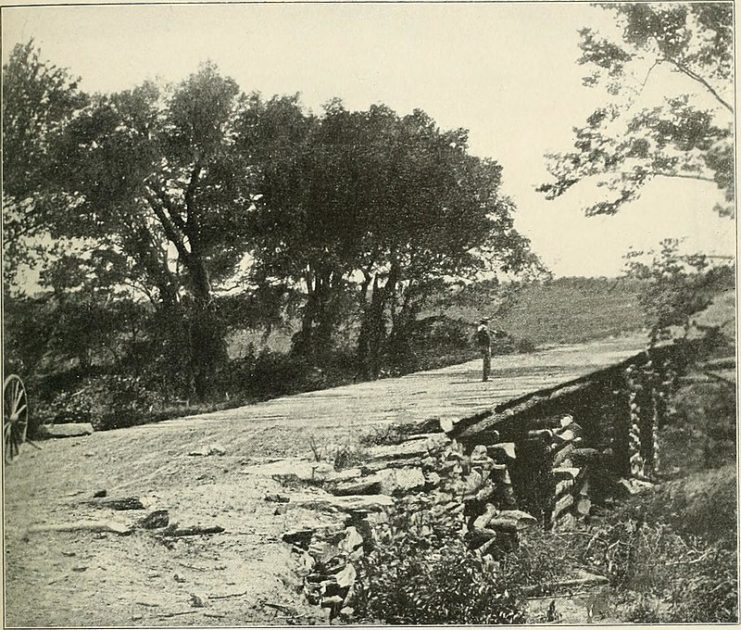

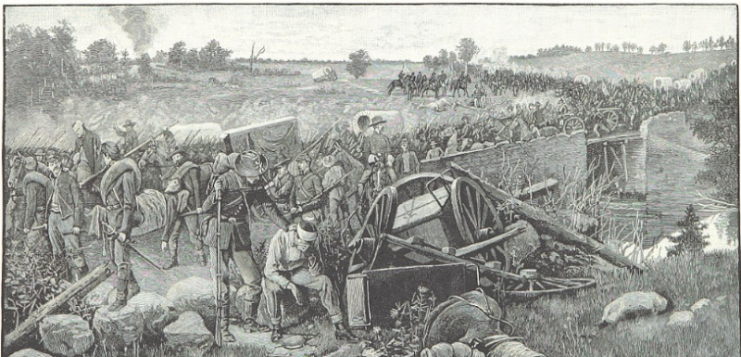

August 30 was a morning of quandary, as Pope considered disagreeing intelligence and weighed his options. Convinced that the Confederates were moving away, the Union commander ordered a pursuit when it was almost noon, but the advance quickly ended when it met Jackson’s forces still hidden behind an unfinished railroad. Pope’s plans now changed to a major attack on Jackson’s line. Porter’s corps and John Hatch’s division attacked Jackson’s right at the “Deep Cut,” a dug-up section of the railroad grade.

However, the Confederate defenders had enough gun support to rebuff the attack. Lee and Longstreet took control of the situation and responded by launching a huge attack against the Union left. Longstreet’s wing, nearly 30,000 strong, swept eastward toward Henry Hill, where the Confederates hoped to cut off Pope’s escape.

Union forces mounted a stubborn defense on Chinn Ridge which bought time for Pope to shift more troops onto Henry Hill and stop a disaster from happening. The Union lines on Henry Hill held as the Confederate attack stalled before sunset. After dark, Pope pulled his beaten army off the field and across Bull Run. Unlike the first battle, which had left the Federals scampering in all directions as quickly as they could, the Union retreat on this occasion was more organized.

In the end, Lee’s tactical skills had paid off against Pope’s massive numbers and that night, despite losing over 7,000 men, the Confederate army could drink to yet another victory.

Pope’s failure was a big disappointment to the Union–it was yet another blow to their pride, and one that would greatly reduce the morale of the Federal troops. Twice they had gone up against the Confederates in the Battle of Bull Run, and twice they had lost.

Read another story from us: A Stonewall Before Bull Run: Jackson in Mexico

There was little left that Pope could do, and he was relieved of his command on September 12, 1862. He was sent to the Department of the Northwest in Minnesota to handle the Dakota War of 1862.