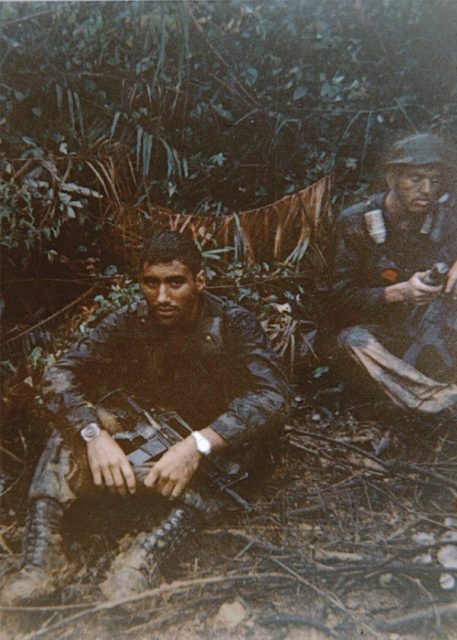

Those who survived a war are often scarred for life by their experiences. Many suffer problems, including the condition known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

It took considerable time for the medical and mental health professions to connect the persistent symptoms of depression, anxiety, chronic insomnia, jumpy body movements, terrifying nightmares, inability to keep a job (resulting in living on the streets), aggressive behaviour, alcoholism, drug abuse, personality changes, difficulty with relationships, a rise in divorces, the high rate of imprisonment and an unacceptably high level of suicide amongst veterans of Vietnam and other war areas, to a disorder now known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

PTSD was officially recognised in 1980 but it took years before it was more generally known and accepted as the debilitating disorder that it is – and while much work is being focused in this area – it is still not yet fully understood.

So many people came home from war zones suffering from confusion, guilt, anger, shame and sorrow. Many of these individuals simply could not cope with the awful burden of such intense feelings – hence the development of the symptoms listed above. PTSD is not easily recognised or treated since people react differently to traumatic stress and the effects of such stress cause a multitude of problems which effectively prevent the sufferer from pursuing a normal life.

The treatment of PTSD has changed radically and work is being done on many fronts to help such persons. Since each person reacts differently to stress, not everyone involved in war or other traumatic situations needs help. There are many veterans living perfectly normal lives. PTSD affects not only War Veterans, but ordinary citizens and even children. It can happen to anyone who has experienced major trauma in their lives, such as for example, as a result of an accident, assault, disaster or death.

Unfortunately, a huge number of vets suffer from some level of PTSD, which possibly explains the large percentage of veterans who are in jail. Shad Meshad (Founder of the National Veteran’s Foundation), himself a Vietnam veteran, noted that 2600 veterans were in the Californian Prison system out of a population of 13500 persons. He further noted that 22 suicides per day are committed by veterans. In order to help PTSD vets, Shad’s National Vet Foundation created a Live Chat website to allow veterans create their own support network.

Information is made available of where and how to get professional help and a Hotline is also available for those in dire need. Shad started counseling groups for Vets In Prisons (VIPs) where they could share their experiences. “Sneaky” James White – a vet who has been in prison since 1978, attended a VIP meeting and became so inspired that he began setting up VIP counseling groups wherever he was placed. He encouraged vets to share their troubles and fears and to support and listen to one another. He encouraged them to study further and to become counselors themselves. Sneaky is much admired for his commitment to the improvement of the lives of all those around him.

Much is being done to help these PTSD sufferers – on many fronts. In the medical and psychological fields, new methods of treatment are being introduced, and many are proving to be reasonably successful.

Psychotherapy, the most common approach, includes, among others, cognitive therapy (encourages improved ways of thinking) and exposure therapy (facing one’s fear) where sometimes Virtual Reality programs are utilized. Another therapy is that of Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR), which is aimed at helping to process traumatic memories so that they can be handled by the sufferer.

It has been found that sufferers often require more than one approach, so most therapies are used in conjunction with other therapies or methods. Many of the therapies need to utilize various drugs for the control of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and nightmares.

Dr. Kate Hendricks Thomas, a Marines Veteran and a Public Health researcher, is convinced that “pills and therapies are not enough to return this active, passionate community [marines and soldiers] to health after trauma.” She had long struggled with her own problems before finding that a study of Yoga meditation was a solution for her. She had grown up in the military field and knew the life intimately. On returning from Vietnam she found herself fighting to control her physical aggression – to the point where she even had to hide her gun.

Her personal relationships were radically affected – so much so, that at one time she felt she could have appeared on a Jerry Springer show! She found that working towards the goal of creating mental fitness and resilience with yoga meditation and other techniques saved her life. She became a trained Yoga instructor and teaches Yoga methods to groups of veterans suffering from various forms of PTSD. She feels that these military people, since they are so competitive, respond much better to a challenge. As she could relate to their sufferings – she gained the trust of her students.

It appears that a number of PTSD practitioners can attest to the value of yoga and yoga-like meditation practices and techniques, having also noticed significant positive improvements in many of their patients.

A recent assessment seems to indicate that a large number of veterans with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder still suffer major depressive disorders and seem to be deteriorating rather than improving. This may well be due to ageing, retirement, chronic illness and declining social security as well as the ongoing difficulties with the management of unwanted memories. Perhaps they too can be helped by practising meditation and breathing exercises.

More practitioners dealing with PTSD veterans seem to be favouring the multi-faceted approach, combining various therapies and techniques tailored to each individual’s particular symptoms and requirements. One is heartened to know that this multi-faceted approach is having the great effect and thus gives us hope for the challenges that may well lie ahead with the veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan.