In medieval times, war in Europe could be a complicated business involving allegiances and family interests that could span the entire continent.

Up until late in the period, the English crown ruled most of western France, which meant plenty of skirmishing with the French king. These battles could be nasty, brutal affairs, but they also provided opportunities to make money.

Many battles would end with prisoners of war being held on either side. While it was a risky business, the sons of nobles who had attempted to make their name on the battlefield but had been captured, could be guaranteed a price for their safe return.

The ransom would have to be raised by the family, and the prisoner would have to promise a cessation of hostilities.

The chivalric codes of the day were set down by a number of scholars, with Geoffroi de Charny among them. Born in 1300, he was one of the most outstanding knights of his day.

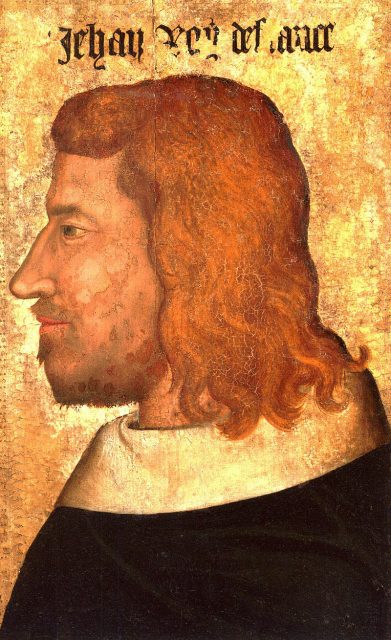

He was honored by King Jean II of France with the role of carrying the Royal Oriflamme flag into battle, which was perhaps one of the most dangerous jobs on the battlefield.

In 1350, he wrote his famous Book of Chivalry which encoded rules of behavior for knights, their monarchs, and men-at-arms.

For Geoffroi De Charny, swordsmanship and prowess with the lance and mace were the most prized knightly skills. War was at the top of the hierarchy regarding suitable contests at arms.

While feats that involved less danger were considered chivalrous and worthy of honor, deeds involving greater peril and done for unselfish reasons (such as the defense of the realm) brought a knight higher renown.

In this way, Geoffroi de Charny’s chivalric code meant that a knight who fought well but failed would usually live to fight another day.

Not all nobles were quite so lucky. On October 25, 1415, at the famous battle of Agincourt, Anthony, Duke of Brabant was a late arrival.

In his haste to get into the action, the thirty-one-year-old Duke dressed in a hurry and was said to have resembled a herald dressed in a trumpeter’s flag. He fought valiantly, but eventually he was forced to surrender and was promptly slaughtered as his ransom value was not immediately obvious.

The treatment of prisoners captured during battle varied but was usually even-handed.

However, at Agincourt, Henry V found his forces under pressure as they were outnumbered by the French. When a counterattack was launched on the King’s baggage train, he ordered that the prisoners be slaughtered so that those guarding them could get back into the fray.

For those in the lower orders, men-at-arms, camp supporters, bearers and the like, being on the losing side meant either slaughter or slavery. If your monarch was on the winning side, you lived to work another day.

If you spoke Gaelic, living on the Celtic fringes of the British Isles, the English were duty bound to give you a hard time. Mass beheadings of Welsh or Scottish prisoners were routine in the early medieval period.

As the centuries passed, times and territory changed. The chivalric system became less workable. Power became more polarised in Paris and London, and regional allegiances became less important.

Those found guilty of trying to increase their sphere of influence by the use of arms became more likely to face accusations of treason. If captured, they would simply be executed rather than ransomed.

War was a messy and dangerous business in medieval Europe, and, as usual, it was the ordinary people who came off worst. If you were a noble prisoner, you might get a room with a view from the top of a tower in your enemy’s castle, so long as you were wearing the correct armor on the day.