As the war in Vietnam raged on, the United States military began to run low on men willing to enlist and serve abroad. To increase the number, the Department of Defense launched Project 100,000, a controversial program aimed at recruiting those individuals who’d previously been denied because they fell below medical and military standards.

The need for more servicemen

Despite the need for more men to fight in Vietnam, President Lyndon B. Johnson didn’t want to draft those in post-secondary education, so he and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara spent two years trying to convince both Congress and the Pentagon to allow them to alter the requirements to pass the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery.

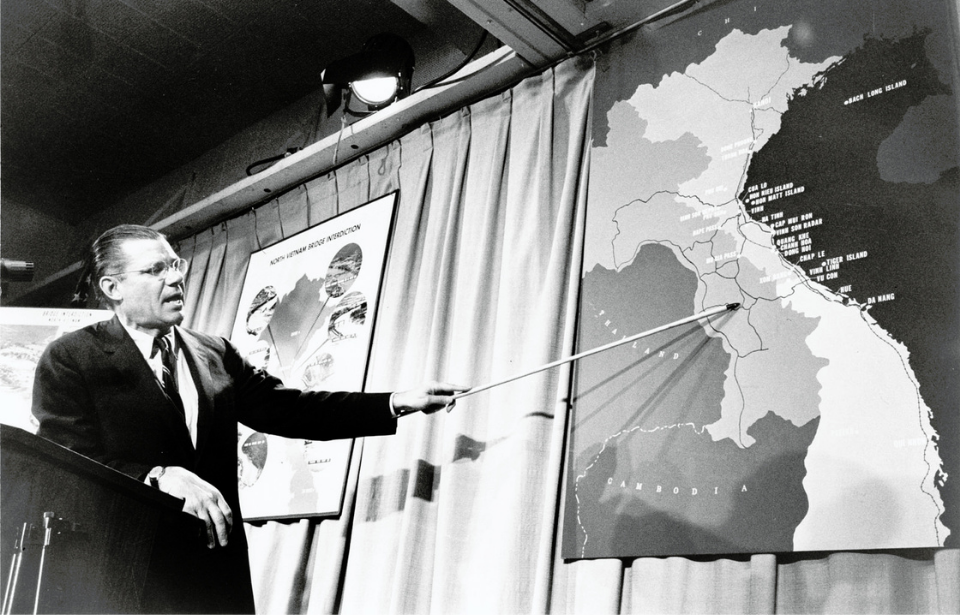

By 1966, it was evident the military was desperate for new recruits, and thus leaders relented to Johnson and McNamara. In August of that year, McNamara went before the Veterans of Foreign Wars to unveil his plan – named Project 100,000 – which aimed to recruit draft rejects and “substandard” volunteers from “poverty-encrusted backgrounds.”

The idea was made to appear as if it were a way of lifting disadvantaged youth out of poverty, and not once did McNamara mention combat duty. He argued that, just because these men had failed certain subjects in high school, it didn’t mean they couldn’t succeed in the military, as it was “the world’s greatest educator of skilled manpower.” He believed this could be accomplished via videotaped lessons.

Project 100,000 launched in October 1966, with the decision made to lower the required score on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery to 10, a six percent drop. This meant that those who’d scored in the 10th to 30th percentile were now eligible for service. While seemingly innovative, it was nothing new. In World War II, the military made it so that those who scored in lower percentiles could be recruited. However, this later made it mandatory for someone to have an IQ of 80 to enlist.

Recruiting soldiers for Project 100,000

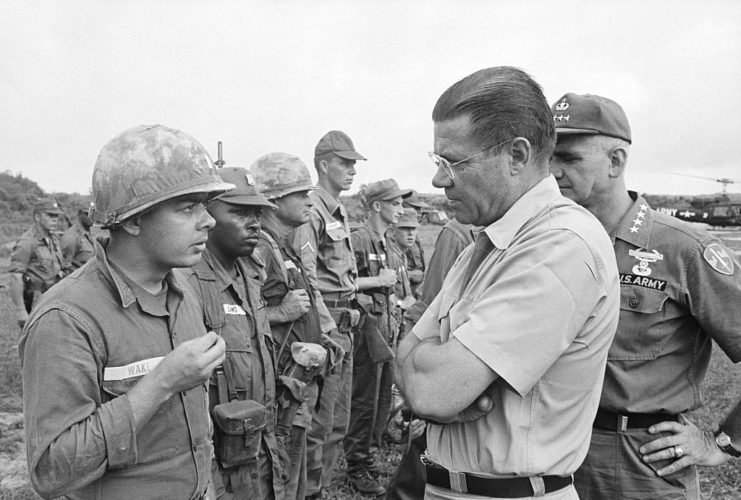

Military recruiters took full advantage of the lowered standard and launched an aggressive publicity campaign, promoting serving in Vietnam as a positive career choice in a glamorous, foreign locale. It was associated with Johnson’s War on Poverty, continuing McNamara’s claims of being a program to help those who were struggling.

The ideal recruit was a high school dropout in his early twenties, with remedial mathematics and reading skills. They sometimes didn’t speak English, and had minor physical and mental impairments. African-Americans and Southerners were over-represented, with Blacks making up around 40 percent of the force after three years, despite only representing 11 percent of the American population. Each underwent basic training, and few received the promised video instruction.

Nearly half of all those who joined Project 100,000 were sent to combat roles, despite recruiters promising otherwise. Those not sent to the frontlines were given positions as cooks, clerks and truck drivers. The Army received the majority of enlistees – around 71 percent – while the Marine Corps and Navy were given 10 percent and the Air Force, nine percent. When compared to their peers, they were 11 times more likely to be reassigned, and between seven and nine times more likely to require remedial training.

Sadly, the men who enlisted under Project 100,000 were not viewed well by their superiors. While publicly classified as “New Standards Men,” they were given the nickname “Moron Corps,” with Johnson privately calling them “second-class fellows.”

The Defense Department began phasing out the program in March of 1971, and by the end of the year, it concluded. It’s estimated 5,478 members died while serving, resulting in a fatality rate three times that of other servicemen. Around 20,270 were wounded, with 500 believed to be amputees.

A controversial heritage

Overall, Project 100,000 was considered highly controversial, and is viewed as a failure in terms of delivering on its goals. This was the view of military leaders, who found that, as the majority of enlistees had difficulty absorbing their training, they not only put themselves in danger, but their comrades as well.

While serving, around half of enlistees – 180,000 – were discharged “under conditions other than honorable,” due to minor issues related to regular military service, including missing duty, going AWOL, talking back to a superior, or abusing drugs or alcohol. This meant they had difficulty finding employment, as the majority of employers refused to hire Vietnam veterans with anything less than an honorable discharge.

These veterans were also denied benefits, including housing assistance, healthcare and employment counseling, leading many to end up unemployed and, in some cases, homeless.

According to John Wilson, a psychologist at Cleveland State University, those who’d served under the program also experienced severe emotional problems, leading to issues with holding down employment, raising families and coping with common, day-to-day activities. As such, they experienced lower incomes and higher divorce rates than their civilian counterparts.

More from us: Dwight H. Johnson: Medal of Honor Recipient and Vietnam War Hero

In 1989, a study sponsored by the Defense Department echoed these concerns. However, McNamara refused to acknowledge the issues and consequences of Project 100,000. For many, it’s one of a number of Vietnam-era failures on his record, and is the reason why he became disliked by military personnel.