When Seal Team Six killed Osama Bin Laden in 2011, they did not do it alone. They had help from a Belgian Malinois dog named Cairo, whose job was to sniff out booby traps. America’s use of animals for special operations goes back much earlier and includes their use as spies. Seriously!

When WWII ended in 1945, the US and the USSR kept up their pretense of friendship. At least until British Prime Minister Winston Churchill mentioned it on March 5, 1946.

He was giving a speech at the Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. Rather than giving an inspiring talk about the wonderful future graduates could expect, he instead gave his famous Iron Curtain speech; accusing the Soviets of wanting to rule the world.

Many accused Churchill of war mongering, but he was right. Tensions between the two new superpowers had been ongoing since the partition of Germany the previous year, but no one wanted to admit it. As such, many historians put the official start of the Cold War with that speech.

Trying to gain the advantage over each other, they not only engaged in an arms and technology race, they also devised unique methods of spying. In 1954, for example, the CIA and British Intelligence set up Operation Gold – digging a tunnel beneath Berlin to access the communications cable of the Soviet Embassy in Zossen.

Their betrayal by a Soviet mole (no pun intended) forced them to invent more creative means. No matter how crazy or outrageous an idea was – the CIA was willing to give it a shot.

The extent of their open-mindedness was not known, however, until 2001. That was the year the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology released previously classified files to Jeffrey Richelson – a senior fellow at Washington’s National Security Archive.

One of their schemes was called “Project Acoustic Kitty.” Although the file is still heavily redacted, it seems American taxpayers in the 1960s forked out over $10 million to see it through. Despite this, it ended with cat-astrophic results!

It began in 1961. Available records do not disclose who came up with the idea, only that the CIA’s Office of Technical Services and its Office of Research and Development gave it the green light.

It sounded like a fantastic idea. Cats are quiet, small, able to go almost anywhere, and do not attract suspicion. Why not use them to spy on the Soviets? Simply attach a power source, microphone, antenna, and transmitter to them.

To succeed, such equipment required to be tiny enough not to attract attention and it needed to withstand being rubbed or licked. Also, a cat’s body chemistry, humidity, temperature, and innate curiosity had to be taken into consideration.

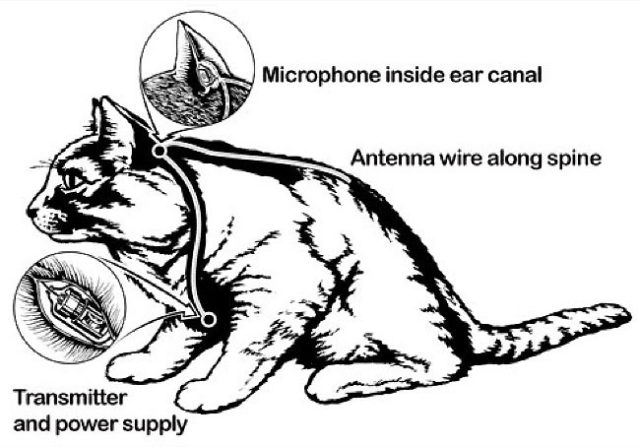

Putting this equipment into a collar would not work, given the extent of their technology back then. The solution? Put them into a cat’s body, instead. The CIA called in audio equipment specialists to work on the problem without telling them what it was for. After using several dummies, they moved on to live experiments.

The result was a ¾-inch-long transmitter surgically implanted at the base of a cat’s skull with a tiny microphone inserted into the ear canal. The battery was put in the chest cavity. A fine mesh wire was used from the base of the neck and was woven into the fur all the way to the tail for the antenna.

The cats were monitored after the operation to see how they reacted to the equipment. They also had to be comfortable and able to move normally so as not to attract attention.

There was concern about how the public might react if they found out. Cyborg kitties!? Still, better those than America fall to communism. It was the Cold War, after all.

They tweaked it, so the wire no longer stuck out of a cat’s neck. It was embedded along the spine, instead. For a test run, they selected a gray-and-white female cat and subjected it to an hour-long operation performed by a veterinarian.

Among those who watched the procedure was an audio technician who had to sit down when he saw blood. Other than that, it went off without a hitch. After recovering, the cat was subjected to further testing when the whole thing was nearly… scratched!

She was easily distracted or bored and would wander off, doing whatever she wanted. In other words, she behaved like any normal cat would. There was also a matter of food. For her, food was more important than issues of national security for the free world and combatting the evils of communism.

This final part of the procedure was addressed with another operation – though exactly how was redacted. She was also trained, which brought the entire expense of the project to a final $20 million.

In 1966, she was ready for her first mission in Washington, DC. Her target were two men sitting on a bench in the park outside the Soviet Embassy on Wisconsin Avenue. She was released from a van crammed with electronic surveillance equipment and scientists who were no doubt excited to be a part of history.

She crossed the street. Unfortunately, so did a cab which ran her over. Given the project’s secrecy, Soviet involvement was ruled out. On the bright side, it showed that she was able to focus on her target without any distractions.

End of story? Not quite. In 2013, Robert Wallace, former director of the CIA’s Office of Technical Service, claimed she did not die. The cat was picked up to avoid her falling into the wrong hands. Her equipment was removed, and the would-be spy went on to live a long and happy life.

Unfortunately for the CIA, however, their $20 million yielded no results. They could not get her or any other cats to do what they wanted, so they finally scrapped the project in 1967.

Instead, they have moved on to using robots, such as the Nano Hummingbird Surveillance and Reconnaissance Aircraft by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Well, hopefully, they did.