Project Underworld was the US Navy’s codename for its joint mission with New York’s crime families. Active from 1942-45, it aimed to obtain information regarding German activity along the Northeastern Seaboard and assist in the Allied invasion of Sicily.

German attacks in the Atlantic

In the first three months following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the US lost 120 merchant ships to German U-boats. The most devastating loss occurred on February 9, 1942, when the SS Normandie, a captured French ocean liner being refitted as a troopship, sunk at Manhattan’s Pier 88.

The FBI investigation suggested a spark from a blowtorch started the fire that brought down the vessel. However, the American public believed it was the work of the Germans. The US Navy agreed, with the US Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) believing free-boating American vessels were resupplying U-boats sailing off the coast of Long Island. They believed it was likely ex-rumrunners put out of business by the end of Prohibition.

The FBI tasked the ONI with uncovering the potential plot. The job fell upon the shoulders of Captain Roscoe MacFall, chief intelligence officer of the Third Naval District.

The Navy struggles to collect information

Between February and May 1942, U-boats sunk more than 100 ships. Plainclothes Naval officials visited the New York docks to obtain information but were met with silence. On March 7, 1942, Captain MacFall met with New York District Attorney Frank Hogan to discuss striking a deal with the city’s Mafia. Hogan, in turn, put MacFall in contact with the head of the New York Rackets Bureau, Murray Gurfein.

MacFall assigned the day-to-day operations to Commander Charles R. Haffenden. He assembled a dedicated team of agents, many of them Italian-Americans versed in the Sicilian dialect spoken by those in the criminal underworld.

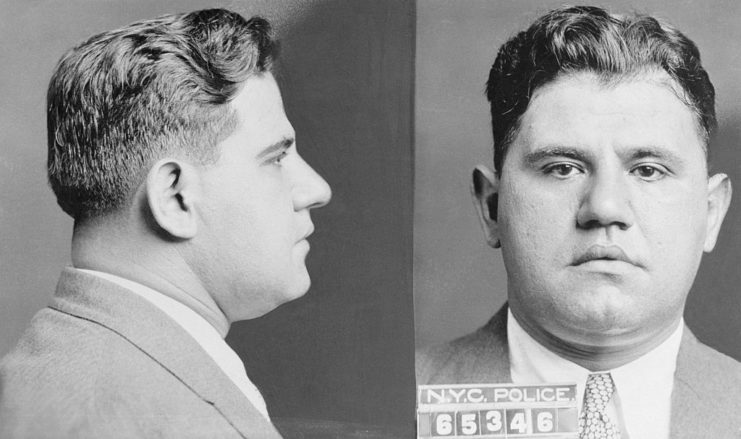

Making contact with Joseph “Socks” Lanza

Worried about a possible disruption on the waterfront, Haffenden set to work creating a security unit. On March 25, 1942, Hogan and Gurfein introduced him to Joseph “Socks” Lanza, a member of the Luciano crime family. Lanza ran the Fulton Fish Market and had a tight grip over the United Seafood Workers Union.

To contact Lanza, Haffenden telephoned his attorney, Joseph Guerin, who pleaded with Lanza, saying, “It’s a matter of great urgency. Many of our ships are being sunk along the Atlantic coast. We suspect German U-boats are being refueled and getting fresh supplies off our coast… You can find out how and where the submarines are being refueled.”

Lanza jumped at the opportunity.

The next morning, Lanza contacted Benjamin Espy, a former bootlegger. They questioned ship suppliers and demanded any unusual purchases of fuel or food be reported to them. The pair even boarded vessels themselves and set up a network of fishermen tasked with keeping an eye out for U-boats.

Haffenden requested union cards to allow his agents to infiltrate long-range fishing vessels. Lanza obliged, allowing the unit to travel with fishing fleets. He also provided cover for more sensitive missions, allowing agents to enter several secure buildings.

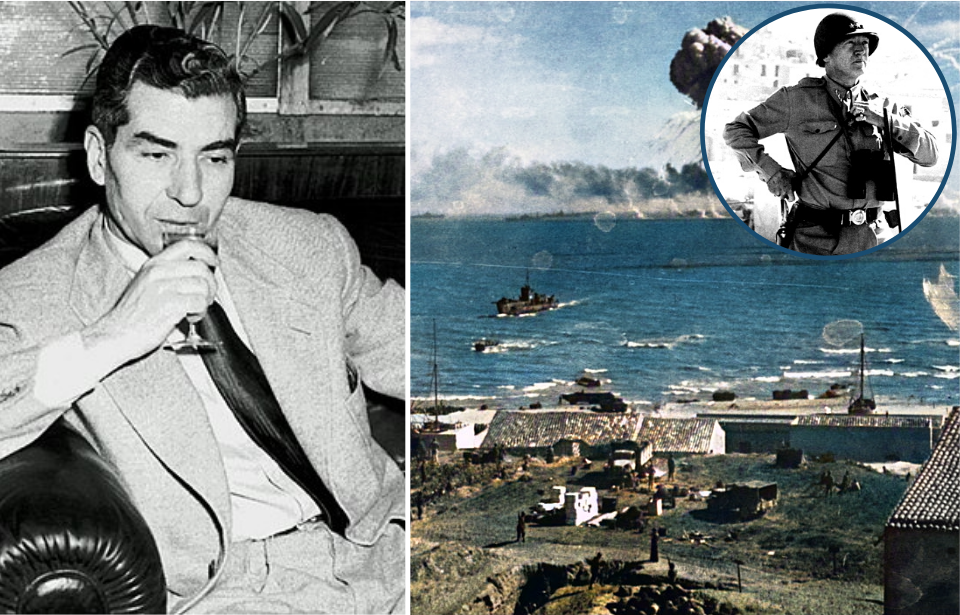

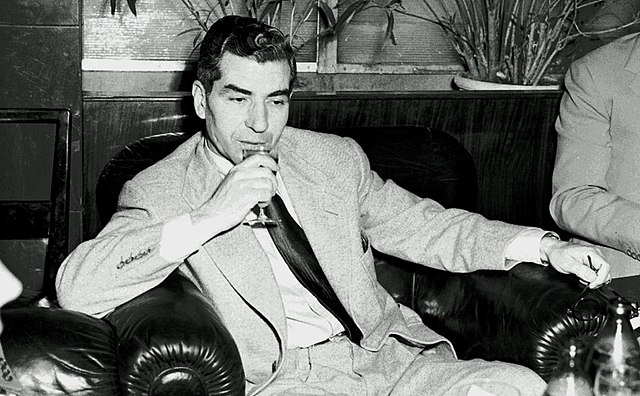

Recruiting Charles “Lucky” Luciano

The Navy knew it needed control of Brooklyn’s docks, which meant securing the approval of Albert Anastasia – better known as the “High Lord Executioner.” Lanza worried about Anastasia’s quick temper and lacked the ability to cross the ethnic divide of New York’s underworld. According to him, the only person capable of doing so was Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

Luciano rose to prominence during the 1930-31 Castellammarese War, becoming the top Mafia don in the country. In 1936, he was convicted of running a prostitution ring and sentenced to 30 to 50 years in prison. To contact the Mafia leader, New York’s district attorney suggested the Navy approach his attorney, Moses Polakoff. He was no longer working for Luciano and told them to contact Meyer “The Little Man” Lansky, a Jewish racketeer.

For his cooperation, Luciano requested a move to Great Meadow, a more comfortable prison. The Navy agreed, but ordered he be deported back to Italy after. They had to proceed with caution, as to not raise the suspicion of the city’s other four crime families. After approaching New York State Corrections Commissioner John A. Lyons, a plan was made to transfer Luciano to Albany with eight decoy inmates.

On June 4, 1942, Lansky, Lanza, and Polakoff visited Luciano at Great Meadow to map out their strategy. They quickly enlisted the help of Joseph Ryan, president of the International Longshoremen’s Association, and his enforcer, Johnny “Cockeye” Dunn. This allowed them to align with their original target, Anastasia.

The Allied invasion of Sicily

With North Africa ready to fall to Allied forces, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Franklin Roosevelt met at the Casablanca Conference. In their meeting, the leaders detailed their plans for the next military war effort: the invasion of Sicily. This meant a change in direction for Project Underworld, with Haffenden forming the F-Target Section.

The Navy used its Sicilian mafia contacts to garner a layout of the invasion zone. They also collected the names of those who would assist in the operation – individuals who disliked Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Once the data was collected, a civilian agent created a map marking every airfield, power plant, and naval base. While this was happening, the ONI formed a pair of two-man commando squads, with alternates from Project Underworld.

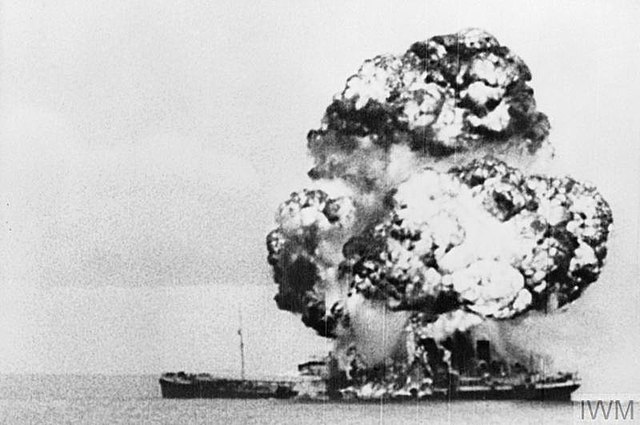

In the late hours of July 9, 1943, the Allies launched a pre-invasion bombardment on the fishing villages of Pachino, Gela, and Marzamemi. Within three days, General George S. Patton‘s Seventh Army and General Bernard Montgomery‘s Eighth Army had brought ashore 181,000 men. They also delivered 14,000 support vehicles, 600 tanks, and over 1,500 pieces of artillery. Among their crew were soldiers working under Haffenden.

Luciano’s name opened doors for the American forces. They obtained valuable information that allowed them to break into the Italian Naval Command and seize classified documents, maps, and codebooks. By July 22, Patton captured Palermo, followed 19 days later by the invasion of Messina, ending the campaign and Project Underworld.

It was intended to remain a secret

The Navy burned all evidence of Project Underworld upon the operation’s conclusion, as it didn’t want the American public to know it had worked with the country’s organized crime network.

The events came to light in 1977, when author Rodney Campbell uncovered the classified 1954 Herlands Investigative Report while working through New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey’s archives. The 101-page report summarized over 3,000 pages of testimony detailing the Navy’s involvement in Project Underworld, revealing a WWII-era mission intent on remaining a secret.