In 1945, it became widely apparent that World War II would soon come to an end. With the surrender of Germany, the only opposition left was the empire of Japan.

The Soviet Union, which had hitherto watched from a distance as several naval battles were fought in the Pacific between other Allied nations and the Imperial Japanese Navy, decided it was finally time to intervene and crush the Japanese opposition.

Following the Tehran conference in November 1943, Premier Joseph Stalin had agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan once the Germans were defeated. At the Yalta conference in February 1945, Stalin consented to join the Pacific conflict against Japan within three months of the war’s end in Europe.

The United Kingdom, United States, and China gave the Japanese Empire an ultimatum with the Potsdam Declaration: surrender, or face utter destruction.

On August 3, Marshal Vasilevsky reported to Stalin that he would be ready to attack Japan in two days if necessary. However, the Soviets were afraid because of the recent and shocking display of the United States’ position as an atomic power during the Hiroshima bombing on August 6.

Therefore the Soviet Union held off its intended invasion of Hokkaido, Japan’s second largest island. The world would soon watch the Nagasaki bombing only three days afterward.

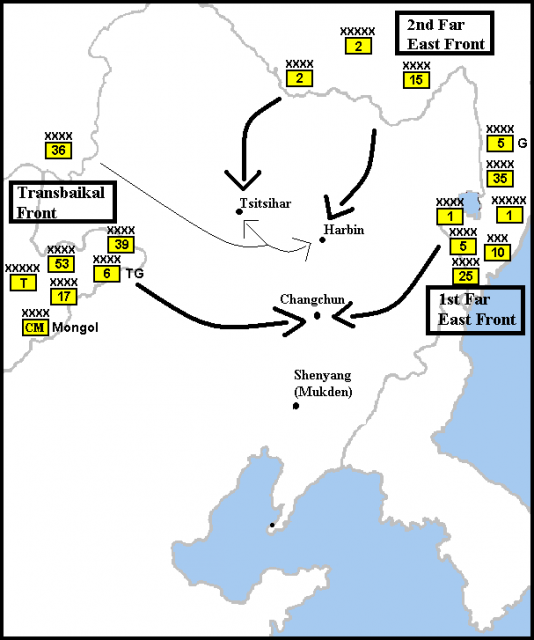

On August 8, the Soviet Union declared war on the Japanese Empire. This declaration was made by Soviet Foreign Prime Minister Vyacheslav Molotov to Japanese ambassador Naotake Satō at 11pm Trans-Baikal time. An hour later, the Soviets began their advance simultaneously on three fronts: to the east, west, and north of Manchuria.

The Japanese military had recently dedicated the majority of its strength and resources to the Pacific battles with the Americans, and kept only a small number of its soldiers to defend against a land invasion closer to home.

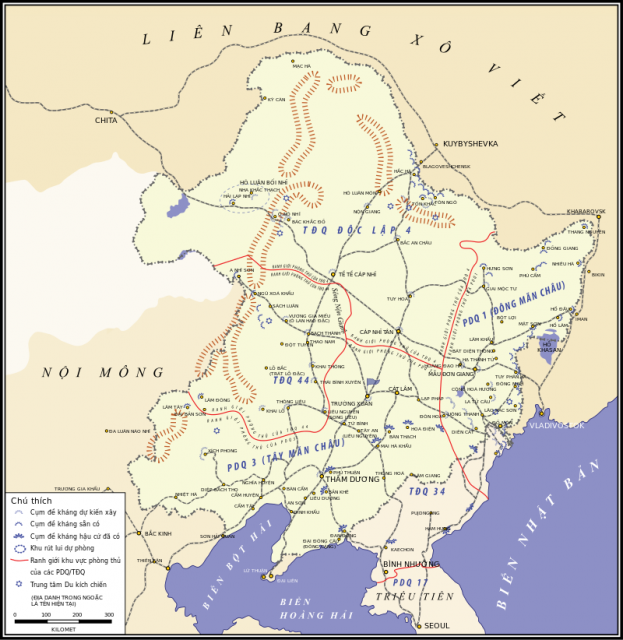

Underestimating the size of the Soviet army, they failed to foresee a three-point attack into Manchuria, working instead with the incorrect assumption that even if there was an invasion, it would come through the old railway line into Hailar. They considered the Greater Khingan route leading directly to the center of Manchuria to be impassable.

From the west, the Red Army attacked through the deserts and mountains of Mongolia, and formed a coalition with Mongolian soldiers who helped defend the rear of the advancing army. The western invasion took the Japanese by surprise, so most of them were away from their designated positions.

The Kwatung army, which was known for its ferocity in battle, was also confused and uncoordinated. Their army commanders away on tactical operations and there was no way to reach them in time because of poor lines of communication. In spite of all this, the Kwatung army still put up a decent formidable defense at Hailar, slowing the Soviet offense.

Simultaneously in the east, the Soviet army attacked through Suifenhe after they had crossed Ussuri, and advanced around Khanka Lake where they met Japanese soldiers. Despite putting up commendable resistance, the Japanese were outnumbered and unprepared for the Soviet invasion.

Meanwhile, Soviet aircraft seized airfields and claimed major landmarks in advance of their land forces. They were also used to carry fuel and other supplies to ground units.

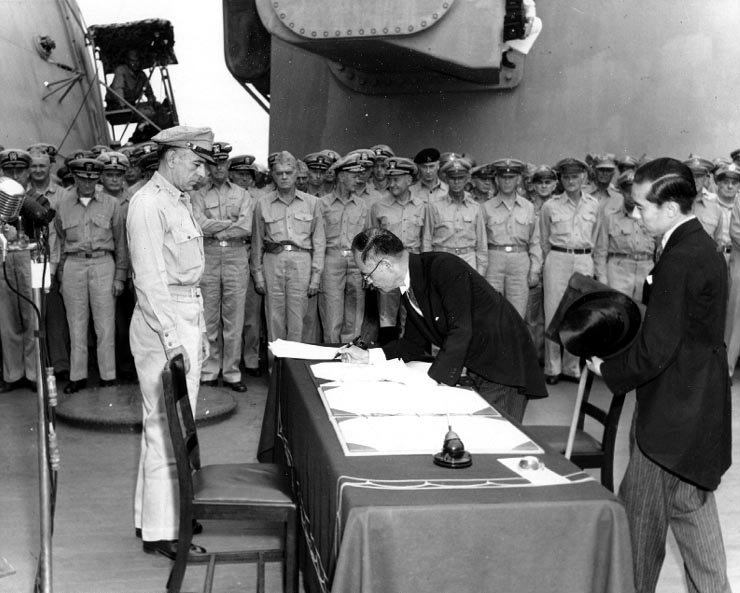

The Red Army continued to advance deep into Manchuria amid resistance from the Japanese soldiers. On 15 August 1945, the Emperor of Japan, Hirohito, recorded a radio broadcast called the Gyokuon-hōsō or Jewel Voice Broadcast, stating that the Japanese government had accepted the Potsdam Declaration.

Despite this announcement, small Japanese resistance groups continued to battle the Soviet soldiers, perhaps because surrendering was repugnant to the Japanese military, or because the Emperor had not used the exact word “surrender,” or perhaps simply because communication lines were poor and transmissions were sometimes incoherent.

Regardless, every so often small fierce battles occurred between the Kwatung soldiers and the Red army, which continued to advance until by August 20 it had reached Mukden, Changchun, and Qiqihar.

The Soviet-Mongolian coalition entered Inner Mongolia, now known as Mengjiang, and took control of Dolon Nur and Kalgan. The Soviet army also successfully captured the Emperor of Manchuria, who was also the former emperor of China, albeit unexpectedly in an airport while awaiting transport to Japan with some of his cabinet members. He was immediately sent to Chita, a city in Siberia near Lake Baikal.

And still the Red Army continued its march, destroying any resistance it encountered along its path. It advanced toward the Korean peninsula, stopping a respectable distance from the Yalu River, and took control of the northern area of the peninsula, leaving the southern portion to the Japanese. This was done to honor the agreement made with the American government to divide the Korean peninsula.

The hugely successful attack on Manchuria by the Soviet army was an important victory for the Allied nations, and was a significant factor in the Japanese government’s decision to surrender unconditionally. This decisive battle led to the partitioning of the Korean peninsula, and also liberated Mongolia and Manchuria and returned them to China, which effectively ended Japanese domination in the region.