The phenomenon of melting glaciers is not breaking news for environmentally concerned people.

However, sometimes such events offer up surprising discoveries, such as the traces of First World War battles that were fought on the mountain tops and, occasionally, the remains of those who died there.

On October 14, 2018, one soldier was finally returned to his family to be buried in his native town of Besana Brianza, roughly 40 kilometers (about 24 miles) north of Milan.

His body had been found in the summer of 2017 by mountain climber, Massimo Chizzoni, alongside his boots, uniform, equipment, and a length of telephone wire.

Usually, there is no way to identify a nameless body since Italian WW1 dog tags consisted of a perishable piece of paper contained in a small box that each soldier carried around his neck.

But a bunch of papers frozen together was found among the body’s personal belongings. Having separated and read the documents, the archeologists were able to identify the remains.

The papers consisted of a receipt, a medical certificate, a holy card, and several postcards, one of which carried a stamp that read “Milan.”

Further research identified the remains as those of Rodolfo Beretta, a member of the “Val d’Intelvi” Battalion of the Fifth Alpini Regiment.

Unit diaries report that on the night of 7/8 November 1916, Rodolfo was buried by an avalanche while bringing supplies from the Lares Pass to the Cavento Pass, on the Adamello glacier (2,920 meters/9,580 feet above sea level).

The Italian Army sent a death notice to his family, but his mother never really believed he was dead. Every day until the day she died, she went to the town railroad station to wait for her son to return.

As the years went by, Rodolfo’s mother, father, and four siblings passed away. His story was seemingly forgotten until a grand-niece found a card in a drawer, commemorating his First Communion.

Meanwhile, miles away, a climber’s ice pick brought human remains back to the light. Careful research gradually revealed a name, a life, and a unit.

As a result, on October 14, 2018, just one year after he was found, Alpino Rodolfo Beretta made his long-awaited return. He was brought to his final resting place by his remaining family and townspeople.

Trench War on the Mountaintops

Hostilities between Italy and Austria-Hungary started on May 24, 1915. The front line ran across a part of the Alps which today forms the border between Lombardy and Trentino (a territory under Austrian rule up until 1918).

Battles were fought at high altitude since the tactic was to hold the mountain peaks in order to dominate the valleys below.

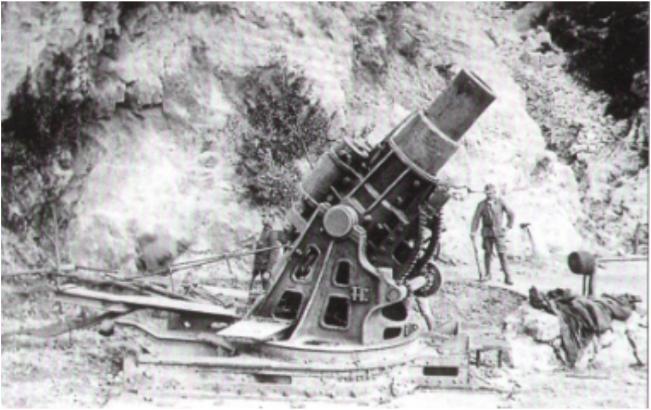

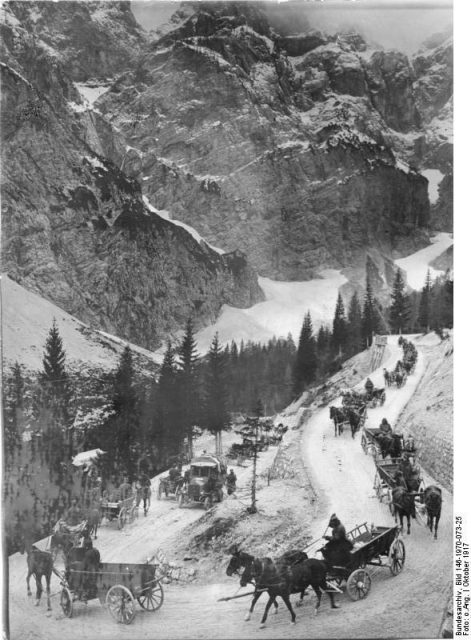

This meant that a lot of military equipment such as machine guns and artillery had to be transported. But first and foremost, construction material was needed to dig and fortify the trenches.

All these supplies were carried up the mountains by the sheer force of men and pack mules, while the large guns were lifted by cranes.

The Austrians hired local civilian porters for the job who were then transferred to far-off corners of the Empire for fear that some of them would secretly cooperate with the Italian Army.

Both Italy and Austria had élite troops (Alpini and Kaiserschützen) specially trained in skiing and rock-climbing, exactly for the purpose of fighting in this extreme environment.

The battles, fought by means of shelling, machine guns, and frontal assault just like on the Western front, included additional difficulties due to the mountain environment in which they were fought: exceptionally rough terrain, severe cold (sometimes dropping to -50 °C), snow, and avalanches.

A small-caliber shot or a chunk of ice detached from a mountaintop would sometimes trigger an avalanche capable of burying dozens of men at once. Such events were feared by men on both sides, and it is reported around ten thousand casualties across the war were caused by such avalanches.

Whenever the men were not busy shooting at each other, they would try to make their life as cozy as possible.

Accommodation was provided in wooden shacks, constructed directly on the mountaintops. Here they would find a bed and a warm meal, and would spend time writing letters to their families or carving metal into elaborate “trench art” souvenirs.

One of these shacks was even found, perfectly intact, on an icy peak in 2014. Even the cableway, used to bring supplies up and down, was still there.

Others were outfitted as gun emplacements or even infirmaries: evacuating the wounded was out of the question, and they had to be treated locally.

Medical equipment was limited, sulphonamides and antibiotics were still to come. Surviving a combat wound was often a matter of luck.

Yet field surgeons did whatever possible to save lives, and their efforts resulted in some progress in medicine. For example, chest surgery, brain surgery, and the modern form of triage are partly based on the harrowing experiences of war.

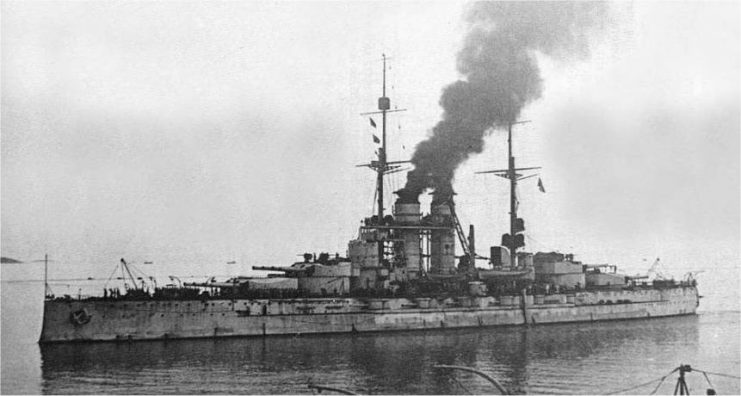

However, the fighting did not take place on the mountaintops alone. The Mediterranean Sea saw a number of clashes between the Italian and Austrian Navies.

Perhaps the most famous is the Battle of Premuda where some Italian fast motorboats (“MAS”) penetrated the harbor and sank the Austrian battleship Szent István.

Air warfare also took place between the fledgling Italian Air Service and Austro-Hungarian aviation troops, mostly in the form of dogfights.

The top Italian ace was Francesco Baracca with 34 kills. His Austrian equivalent was Godwin Brumowski with 35 kills.

Although strategic bombing was not very well-developed at the time, some Italian cities even had the dubious privilege of being the very first to be bombed from the air: Milan, Brescia, Padua, and Venice were the most important.

When Austrian and German forces broke through Italian lines at Caporetto on November 24, 1917, war moved from the mountains into the Venetian and Friulan valleys, causing hundreds of thousands of Italian civilians to flee their homes and become refugees.

Italian forces established a line of resistance along the Piave river. They held their ground with help from the “99 Boys,” the 18-year-olds that were drafted in to replace the Army’s terrible losses.

“Pompei in the Ice”

The final victory of the Italian Army on their Austrian-Hungarian foe took place on November 4, 1918, one week prior to the official “Armistice Day” which marked the end of three years of grueling pain and suffering on both sides.

However, this was not yet the end of the troubles for Italy, which experienced a period of civil unrest that ultimately brought about the rise of fascism.

The mountain battlefields of World War 1 were deserted and all their content simply abandoned. The locals invented a new trade: the “recuperante.” i.e. “scavenger.”

Men returned to the battlefields and recovered whatever items the ice had not taken over in order to reuse them or sell them to factories craving scrap metal, primarily brass, copper, and iron.

It was a dangerous job and it certainly took a toll on scavengers due to the unexploded ordnance and of the inherent danger of the mountains.

In those mountainous areas, well before the “boom” of winter tourism, poverty was endemic and the alternative was starving or migrating out of the country, so they accepted the risk. In the end, it was just another battle – this time for everyday survival.

When the glaciers started to thaw significantly, they revealed trenches and huts so remarkably preserved that it was as if they had been left only a few days before.

The remains constituted a perfect “Pompeii in the ice,” a time capsule bearing an imprint of everyday life. Weapons had been abandoned there, but also stoves, tables, pipes, inkpots, boxes, uniforms, headwear, and overshoes made of woven straw.

Finding traces of World War One is still pretty ordinary in the Italian Alps, even when the “traces” are three Austrian Kaiserschützen mummified by ice with their clothing pretty much intact. That was a discovery made in 2004.

Read another story from us: Elite Italian Shock Troops – The Arditi: We Either Win, Or We All Die

It is like an old movie reel still playing after 100 years.

Many of the items found on glaciers are today in museums. Visiting them, or having a walk in the uncovered trenches and forts is the best way to understand the soldiers’ experience and learn about a major part of Europe’s history that should never be forgotten.