It is said that the 1777 Battle of Saratoga was the most crucial and decisive during the American Revolutionary War. Often coined as the turning point of the conflict, the victory at Saratoga boosted the spirit and morale of the Americans and compelled the French to provide aid and support to the revolution.

John Burgoyne and the Plan to Capture Albany

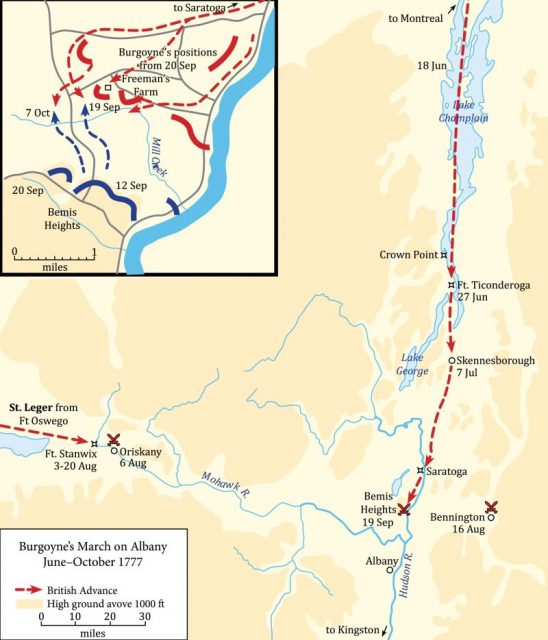

General Burgoyne, the senior British commander in Canada (though nominally under Sir Guy Carleton), used his considerable influence with powerful London war policy-makers to gain approval to march a formidable British army south into New York with the intent of capturing Albany and splitting the colonies.

The success of the plan depended upon Sir William Howe, technically Burgoyne’s senior as commander-in-chief in North America, sending an army up the Hudson River to support Burgoyne’s march south. Howe never received a direct order to that effect, however, and resented the fact that Burgoyne had been given complete independence to use the Northern Army for his own purposes.

At the time Burgoyne began preparing his army in June 1777, he was unaware that Howe was not planning to send any troops north. Howe was busy brilliantly defeating George Washington in a series of skirmishes that ended with the British occupation of Philadelphia, where only a year earlier the Declaration of Independence had been adopted.

Howe’s second in command, Sir Henry Clinton, remained in New York with a much smaller force and, although initially supportive of Burgoyne’s plan, had no intention of weakening his position. As Burgoyne began his march into the interior after debarking at Lake George, he had no way of knowing that his 7,000 men would be forced to fight an army four times as large without the assumed support from Howe.

Benedict Arnold at Bemis Heights

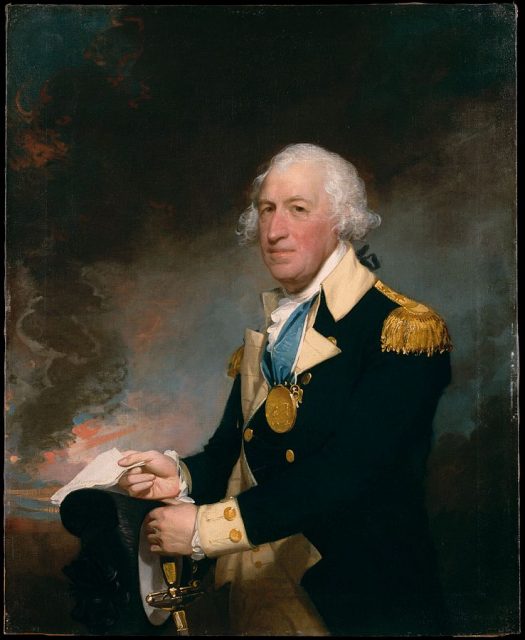

Although General Philip Schuyler was responsible for American defenses and the eventual strategy that would result in the encirclement of Burgoyne, he was replaced by Horatio Gates, referred to by historians as the most political of all American generals. Burgoyne, arrogant and uncompromising, severely overextended his supply train, making it easier for the Americans to defeat him at Saratoga. Additionally, Burgoyne’s army included hundreds of women and dependents.

After some minor victories along the route (including the capture of Ticonderoga), Burgoyne lost a sizable number of troops at Bennington where they were ambushed. His march, however, was halted at Bemis Heights. American troops under Benedict Arnold inflicted heavy casualties, forcing Burgoyne to withdraw north to Saratoga where his army dug in.

At this point Burgoyne was still able to evacuate northward, an action counseled by some senior officers, including Baron von Riedesel, commander of the two German brigades. But Burgoyne still anticipated relief from either Howe or Clinton.

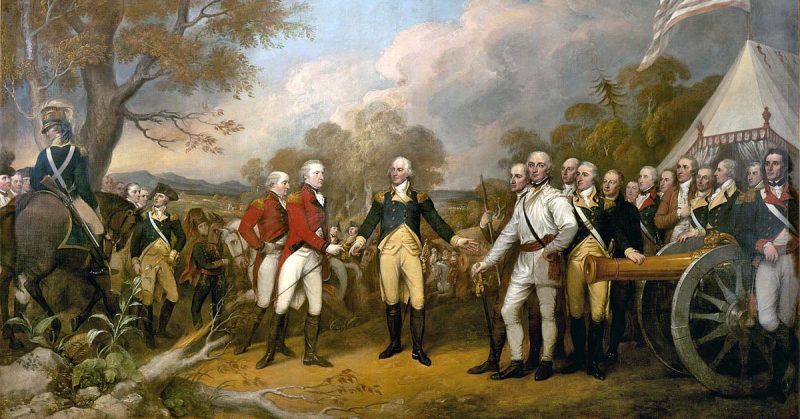

The ensuing battle, including an attack on Burgoyne’s center by Benedict Arnold, who was acting against orders, resulted in such carnage that Burgoyne was forced to seek surrender terms. His army had less than a week’s worth of food and, as one desperate German officer wrote, “Never can the Jews have longed more for the coming of the Messiah than we longed for the arrival of General Clinton.”

Terms and Aftermath of the Battle of Saratoga

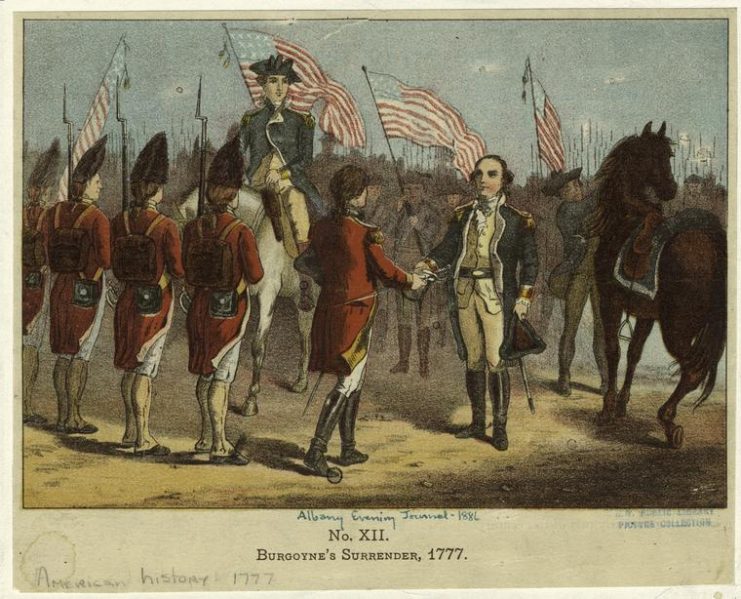

Horatio Gates accepted Burgoyne’s counter-terms to the unconditional surrender he had requested. Although Burgoyne threatened to fight to the death if his terms were not accepted, Gates would be undone by the generous terms that included marching the prisoners to Boston and allowing them safe passage home on the promise not to fight in America again.

Washington, jealous of Gates’ victory, pressed home this point. An exiled Continental Congress later abrogated the terms. Saratoga was a prime example of why the British lost the war.