The Romans quickly busied themselves training sailors, although Rome was first and foremost a land power.

Various historians have pondered what might have happened had Rome not defeated Carthage during the Punic Wars. Would the Occident or Europe exist today as we know them? And what about Christianity, Roman law or Latin-based languages?

Many of us have heard about the tenacious Carthaginian general, Hannibal, and how he drove war elephants across the Alps during the Second Punic War. But what about the First Punic War, a way that often falls by the wayside in modern historical interest?

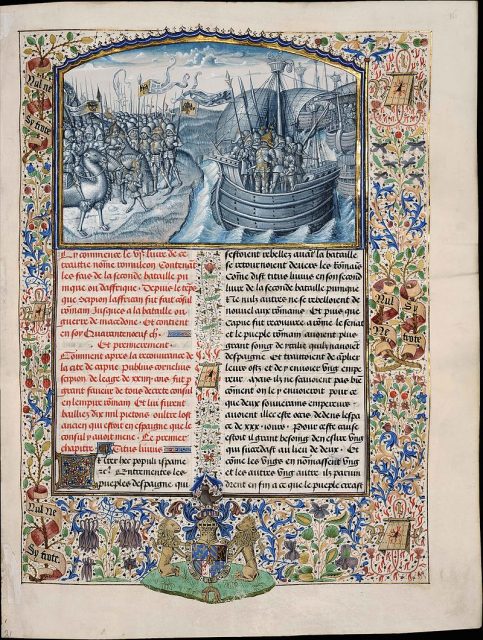

The First Punic War involved some of the largest and bloodiest sea battles in ancient history. Titanic is an apt word to describe these encounters in terms of the manpower and equipment involved as well as the influence they had on the course of history.

The Battle of Mylae occurred in 260 B.C. when Rome’s fledgling navy faced off against Carthage. The battle was the first naval confrontation of the First Punic War and ended with a surprising Roman victory. Out of the 130 Carthaginian galleys involved, 44 were lost along with 10,000 men and their commander was executed by order of the ruling council in Carthage. Meanwhile, the city of Rome was rapt with victory.

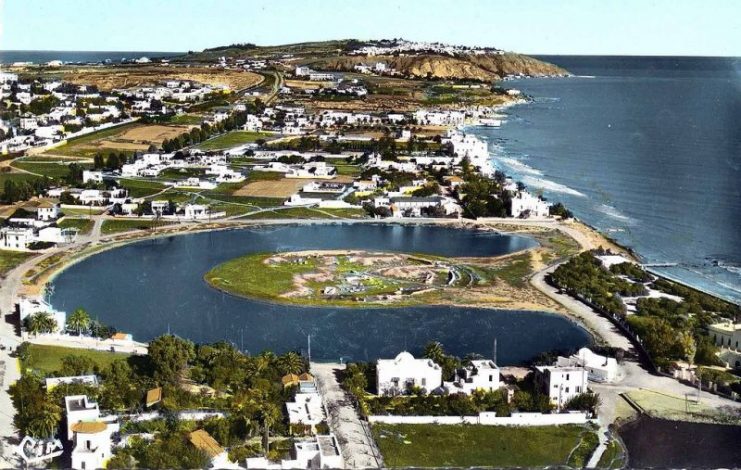

Rome’s enemy at the time was not just some pirate captain, but the largest naval power in the Mediterranean Sea. The meeting at Mylae (modern-day Milazzo) on the northern coast of Sicily set the stage for Rome’s eventual victory in the First Punic War. As a result, the republic would rise to become the greatest hegemonic power in the western Mediterranean and all antiquity.

Polybius is the main historical source for the period, despite being born a little more than half a century after the Battle of Mylae. He is considered one of the most important historians of antiquity. Furthermore, he witnessed the sacking of Carthage at the end of the Third Punic War in 146 B.C. Many historians since have almost blindly submitted to his authority.

Polybius also wrote about another naval confrontation between the two Mediterranean rivals that makes the Battle of Mylae pale in comparison. But first, what was the situation in the Western Mediterranean before the war? Who were the two great powers of Carthage and Rome?

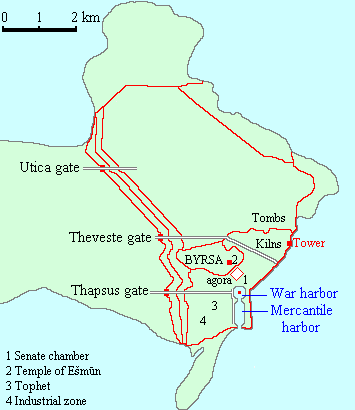

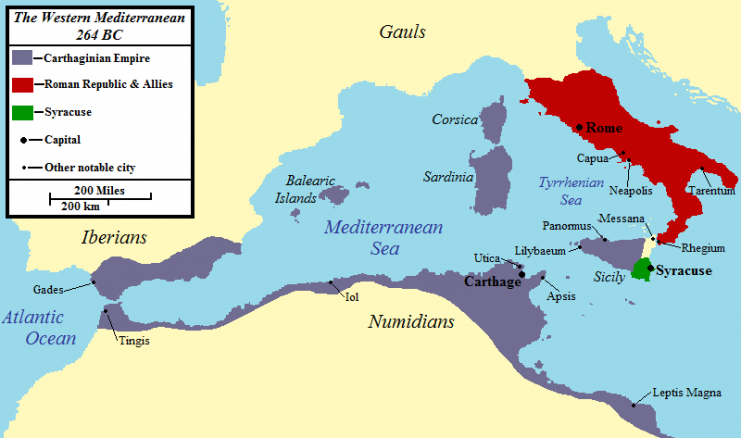

The background preceding the First Punic War is easily explained. After defending against King Pyrrhus I of Epicurus, the Roman Republic rose to become the leading power on the Italian peninsula. Rome’s further expansion could only be checked by the formidable trading power of Carthage which controlled colonies and fortresses stretching from modern-day Tunisia to Spain and on Sardinia and Sicily.

In 264 B.C., the free city of Messina in Sicily sent a request for Rome to intervene on the island after decades of Carthaginian influence.

The two nations waged war differently

While the Carthaginians employed expensive and highly trained mercenaries, the Roman aristocracy was able to rely on its superior reservoir of highly efficient foot soldiers, the prized Roman Legionaries. These soldiers were the buzz saw of antiquity that used their superior discipline to carve a path through enemy ranks. However, lacking a naval fleet to match that of the maritime titan Carthage, their rival’s territory remained unassailable for Rome.

https://youtu.be/eN1IML5g34I

According to Polybius, a stranded Carthaginian warship is said to have catapulted Rome into the sea. The warship was a quinquereme, a classic galley and the pride of the Carthaginian fleet before the outbreak of the war.

The Romans now had a prototype from which to model their fleet on. Without such a stroke of luck, Rome’s maritime inexperience would have made it impossible to even consider conquering Carthage.

The Romans quickly busied themselves with training sailors since Rome was first and foremost a land power. They had to find a way of infusing their terrestrial martial prowess onto the Mediterranean, a sea they would one day call “Mare Nostrum,” or “Our Sea.” Nonetheless, Rome’s ships remained cumbersome and poorly built and were no match for Carthage’s sleek and maneuverable vessels that had dominated the waves for hundreds of years.

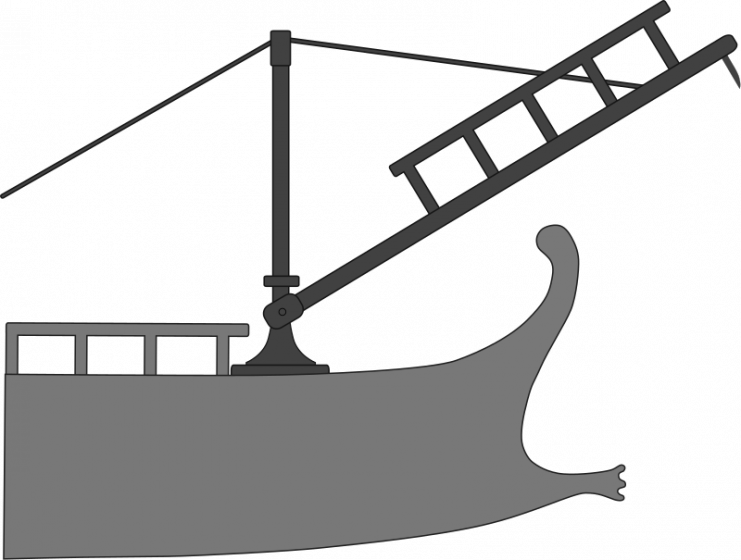

The invention of the “corvus,” or the “crow” changed everything and altered the course of history.

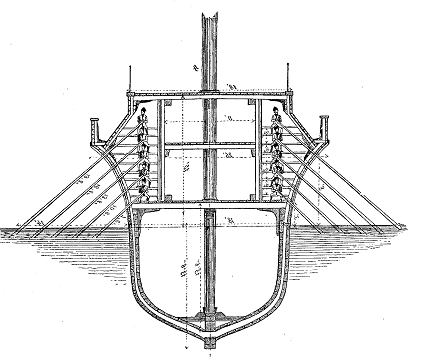

Polybius is the only remaining authority available that describes the design of the corvus. This ingenious boarding device was most likely located close to the bow of the war galley, with Polybius explaining that the contraption was 36 foot long and 4 foot wide.

The idea was to get close enough to the enemy ship for the bridge to be lowered using a system of pulleys. On contact, the heavy spike shaped beak on the underside of the device would crash into the timber on the enemy ship’s deck. Roman legionaries would then cross the narrow gap to overrun the other vessel.

This stroke of genius, which some historians attribute to Archimedes of Syracuse, allowed the Romans to effectively transform a naval engagement into a land battle.

Yet the corvus did not survive for very long due to its cumbersome construction which increased ship instability during storms. The corvus would disappear from history after Rome’s greatest naval victory.

The Battle of Cape Ecnomus of 256 B.C.

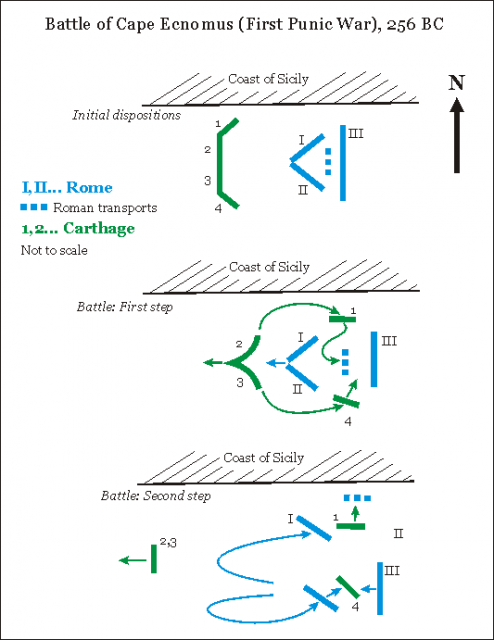

The Romans quickly put their newly enlarged fleet to use after proving it at Mylae. The consuls of the year, Lucius Manlius and Marcus Atilius Regulus, sailed around Pachynum in southeastern Sicily and took up position near the mouth of the Himera river and the Ecnomus Mountain (Monte di Licata).

The Carthaginian fleet awaited them at Port Heraclea, under the command of Hamilcar (not Hannibal’s father) and Hanno.

The Romans had 330 ships, each with 300 oarsmen and 120 soldiers on board, with the combined Roman fleet carrying about 140,000 men. The Carthaginians meanwhile had 350 galleys crewed by an estimated 150,000 men.

A total of 300,000 men aboard 680 ships clashed at Cape Ecnomus. By comparison, the First World War Battle of Jutland between the United Kingdom and Imperial Germany involved a mere 200 ships and 100,000 men.

The Romans divided their fleet into four squadrons, with two placed at an acute angle to form a wedge. The two ships belonging to the consuls were in the vanguard. The third squadron formed the third edge of a triangle in relation to the first two squadrons, transport ships in tow.

The Carthaginians also formed their fleet into four divisions. Their primary goal was to prevent the Romans from reaching the Carthaginian heartland in present-day Tunis. From the onset of the battle, the Carthaginians did their utmost to dissolve the compact mass of Roman ships.

The Roman consuls opened up the hostilities at the head of the Roman wedge. The Carthaginians responded by feigning a retreat, which resulted in the Roman’s dividing their forces and creating three separate theaters of combat.

To the Romans’ surprise, the Carthaginians were not the able seamen they had feared. The increased Carthaginian fleet size and the inexperience of the freshly recruited sailors negated their previous maritime experience advantage. Furthermore, the Romans had learned a lot in the four years since their last encounter and their ships were of much sturdier construction.

Carthaginian ramming tactics proved largely ineffective and the battle quickly turned into a shapeless nautical brawl. This was unfortunate for the Carthaginians since the Romans excelled at this type of fight. The corvus soon gave them the advantage–-bloodthirsty legionaries swarmed onto the Carthaginian quinqueremes, carving through their foe like a hot knife through butter.

The Carthaginians lost 30 ships and a further 64 ships were taken, against just 24 Roman galleys sunk. The battle was a resounding defeat for Carthage, with 30,000 to 40,000 Carthaginians either killed or captured.

The prows of the captured Carthaginian ships ended up in Rome and would adorn the rostra in the Forum Romanum for many years.

Read another story from us: How War Built An Empire: Conflicts Ensured Rome’s Future Growth

The Carthaginians never again regained supremacy of the sea. Not long after their victory, Rome lost over 100,000 men and 300 ships in a vicious storm, but the Romans would ultimately prove victorious in 241 BC at the close of the First Punic War.

Carthage was subjected to harsh war reparations and territory losses after the 23-year conflict. But they would rise again to fight in the Second Punic War and almost brought Rome to its knees–-but that is a story for another day.