At its height, the Roman Empire spanned huge swathes of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Their military prowess, groundbreaking use of strategy and enormous technological advancements allowed them to become a seemingly invincible force. However, there were many instances of individual men and women who tried to stand up to the might of Rome, rallying their countrymen behind them. From daring uprisings to cunning acts of treachery, here are five of Rome’s greatest enemies.

Hannibal

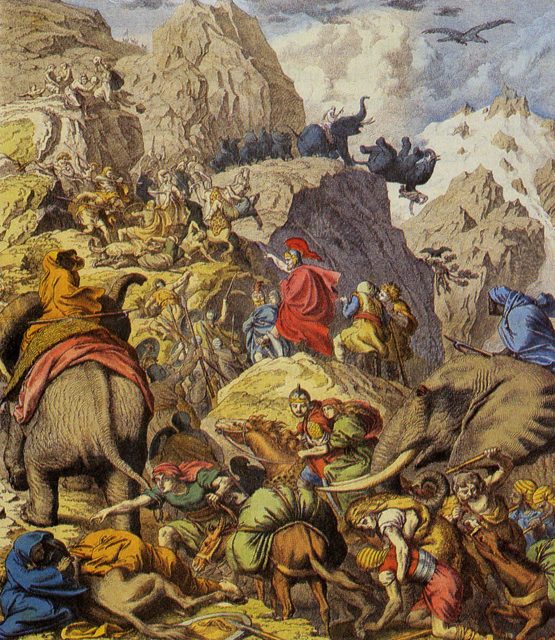

When we think about Rome’s enemies, it’s hard not to come up with one name right away – Hannibal of Carthage. Although – like so many adversaries of the Empire – Hannibal was eventually beaten, his incredible campaign has become one of the most well-known on this list. With a huge army at his back and a remarkable number of elephants in his ranks, he led the Carthaginian forces through the Alps, entering Rome’s territories from the north.

With a shrewd approach to strategy and a powerful military at his disposal, Hannibal posed a real threat to Rome, and won numerous engagements before the tide finally turned against him. Rome worked hard to stall and delay his advance, while slowly weakening his army through numerous small harrying attacks.

Eventually, as the stalemate dragged on, Hannibal withdrew, returning to Carthage to defend it from an imminent attack by Roman general Scipio Africanus. There, at the battle of Zama, Hannibal was decisively defeated, and he fled into exile. Even after he was vanquished, however, the Carthaginian leader is remembered as one of Rome’s greatest and worthiest foes.

Boudicca

Roman Britain was plunged into chaos when the warrior queen Boudicca instigated a bloody uprising. Her husband Prasutagus ruled East Anglian people of the Iceni, and had been allowed to live in peace by the powers of Rome. However, after his death, the Imperial authorities decided that they wanted to control the region directly, and began seizing land and property previously held by local tribes. After confronting them, Roman soldiers flogged Boudicca and her daughters were raped, sparking outrage amongst the British peoples.

Neighboring tribes joined their cause, and the rebel army launched a brutal assault on the occupying Romans. Several key cities and commercial hubs were attacked and burned to the ground, while their occupants were slaughtered. Eventually, in 61 AD, Boudicca’s revolt came to a sudden end at the Battle of Watling Street. A small group of Roman soldiers managed to use the terrain and their own tactical prowess to decimate the much larger rebel army. Seeing her followers massacred, Boudicca retreated and ended her own life shortly afterward with poison. Despite her tragic end, she is to this day considered one of the most courageous enemies of the Empire.

Attila the Hun

Had it not been for a particularly bad nosebleed, history might have taken a very different turn. Attila was the leader of the Hunnic Empire. This union brought together Huns, Alans, Ostrogoths and many other groups in one confederation, and during Attila’s lifetime he managed to make enormous inroads into Roman-occupied territory, particularly in Eastern Europe. After an attempted assassination attempt, backed by the Roman authorities, Attila was infuriated and pushed even harder into Europe. The Hunnic forces drew steadily closer to Rome itself, and things looked grim for the capital.

Attila’s armies eventually entered the Italian peninsula itself, but there a major problem presented itself. Rome had suffered through a particularly bad harvest the year before, and this had been made even worse by the initial ravages of the Huns. This meant that the invading army had little access to resources and food, and could replenish their supplies as they advanced. Attila withdrew, and died soon afterwards. On his wedding night, the man who almost conquered the heart of the Roman Empire suffered a sudden nosebleed and choked to death on his own blood.

Vercingetorix

Although his insurgency ended in defeat at the Siege of Alesia, Vercingetorix is remembered as a bold military leader and a great unifier for his countrymen. Julius Caesar had pursued a strategy of “divide-and-conquer” in Gaul, sowing descent and separatism amongst the local tribes. Some factions he favoured over others, supplying them with extra resources and financial support, and for some time he was able to keep the Gauls subdued. As a result of this, when Vercingetorix tried to instigate a revolt, he was cast out of his tribe. He managed to gather support elsewhere in the country, however, and soon launched a number of attacks on Roman-occupied cities and settlements.

Although Rome had an edge in numbers and equipment, Vercingetorix used his native terrain to his advantage. Whenever this wasn’t enough, he would retreat swiftly from the Roman advance, burning the crops as he went to and depriving his enemies of any fresh resources. In the end, however, he was unable to gain significant ground against the Romans, and was forced to withdraw to the city of Alesia. Here, in the autumn of 52 BC, Vercingetorix surrendered, to avoid any more of his countrymen dying. Some of his followers were allowed to live, although many more were put to death. The rebel leader himself was held prisoner in the city of Rome, only to be executed six years later.

Arminius

Once a friend to Rome, Arminius became a hated enemy of the Empire after he betrayed them in the battle of Teutoburg Forest. Although originally from Germania, he was raised as a captive of the Romans, and as such received a military education, citizenship and a title of nobility. After years spent training to be a Roman commander, he returned to his native land and put a devastatingly effective plan into action. He sent word that a rebellion was breaking out, and requested help. Rome sent a large detachment of men through Teutoburg Forest to aid the man they thought of as one of their own.

The line of soldiers was stretched out as the moved through the trees, leaving them vulnerable, and Arminius chose this moment to spring a deadly trap. It is estimated that as many as 20,000 Roman soldiers died there, including their general Varus, who threw himself on his own sword. Rome was outraged by the betrayal and attempted to stage numerous counterattacks, but the Battle of Teutoburg Forest became a turning point in history, and they never manage to reclaim the Germanic territories.