In an interview with the BBC, Ruth Winkelmann described the terror of living through the infamous Kristallnacht or Night of the Broken Glass, when the Nazi persecution of the Jews turned violent.

The memories of those that lived through this hellish episode are as vivid today as they were on that fateful night of November 10, 1938.

Ms. Winkelmann, now 90 years old, described how her loving father took his two little daughters into his arms and told them that this was the start of a difficult period but that they would do their best to live through it.

In 1935 the Nazi regime passed the Nuremberg laws, which codified who was considered Jewish and who was not. These laws became the basis of the persecution against the Jews, and the definition of Jewishness became the difference between people living and dying.

The legislation also discriminated against those like Elly, Ruth’s mother, who was born Protestant but converted to Judaism when she married Ruth’s father.

The BBC interview took place in Berlin, and Ruth remembers the smoke billowing out of the New Synagogue in Berlin, 80 years ago. She was just ten years old as her father drove her to school on that fateful morning.

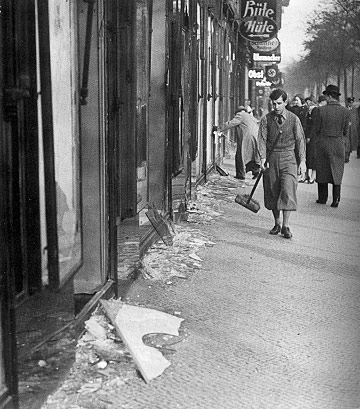

As they drove, they saw the start of the troubles that were to escalate into outright violence. They saw broken glass from smashed windows, and on one shop the slogan ‘Jew’ had been painted along with a smeared Star of David.

They were horrified to see Nazi stormtroopers grab a Jewish man wearing a black coat and paint a Star of David onto his back before beating him. She was terrified and shaking but recollects feeling safe because her father was next to her. Still, Ruth had every reason to fear.

She went to a Jewish school, although it was not an Orthodox school. That morning the teachers rushed all the children into an assembly, and they learned how the city they lived in had turned against those of her religion. They heard of the destruction of Jewish shops and businesses and how Jewish people were killed.

The students peered out the windows and watched the flags carried by the Nazi stormtroopers as they marched along the streets.

She remembers the noise made by the stormtroopers and how the school was barricaded off. Slogans such as “Jews Out” were daubed all over the building, accompanied by the Star of David.

The schoolgirls had to leave the school buildings by creeping through the loft and attics of the buildings until they found their way to a back courtyard and down to the street. The little girls were especially terrified when their teachers told them to return straight home as the stormtroopers were still on the roads.

When Ruth arrived back at her home, she discovered that not only were the children terrified but her parents and grandparents were also just as frightened.

They had seen the stormtroopers break into the Synagogue, destroying the Torah and setting fire to everything. This was only one of many hundreds of Jewish places of worship destroyed that day.

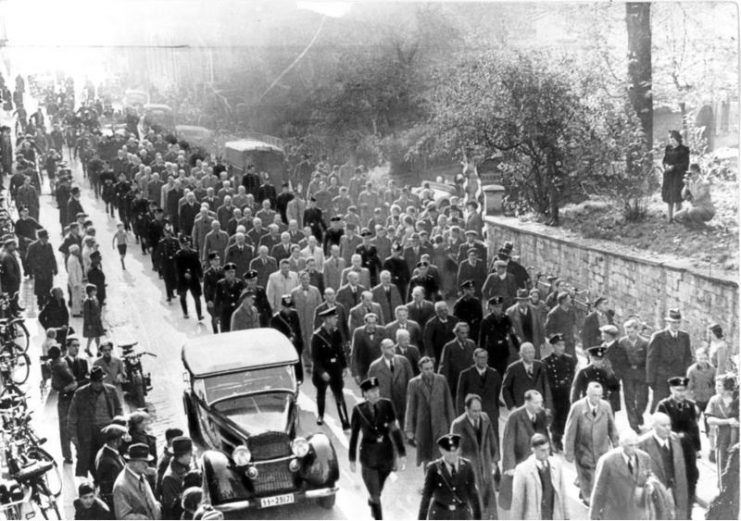

The Nazis were not content with destroying the synagogues but also destroyed Jewish schools, hospitals and close to 7,500 businesses. On this fateful night close to 100 people were killed and 30,000 Jewish men were rounded up for transportation to the concentration camps.

Ruth realized what had happened when the fathers of her school friends went missing. First, the Polish Jewish men were deported followed by the German Jewish men.

Ruth described the life that she and her parents were forced to endure. They had to sell their scrap metal business due to the Nuremberg laws. As her parents then had no income, they had to sell their home.

Later Ruth’s family were nearly all deported, and of the sixteen sent to the camps, only one survived. Her father’s parents starved to death at Theresienstadt Camp.

Ruth will never forget Kristallnacht, and she believes that the pogrom took away her childhood and that day she became an adult. She still has her ID card issued by the Nazis.

The race laws enacted in Germany at the time were involved, and Ruth and her sister were classified as “first degree mixed-race,” as her father was Jewish, but her mother was Protestant, so according to the Nazis she was still “Aryan.”

Unfortunately, since the two girls were registered as Jewish community members, they were deemed to be Jewish by the authorities. Because of this classification they had to sew a yellow star onto their clothes and add the name “Sara” to their given names.

Ruth’s parents divorced in an attempt to save the two girls, but this left her father very vulnerable, and in 1943 he was sent to Auschwitz. In the time that he was incarcerated, her father sent just four postcards home to his little girls.

Faded now, the cards make it clear that he was doing his best to shield his children from the horrors that he saw around him.

Ruth’s father was incarcerated in one of the sub-camps associated with Auschwitz, Monowitz. At this camp, the prisoners had to work for the chemical industry.

Her father was working on a scaffold one day when he was pushed off. As he was taken away in an ambulance equipped with poison gas, no one expected to see him alive again, but he wasn’t gassed then. Ruth discovered from the records at Auschwitz that he died in January 1944.

Ruth and her mother and sister were finding food increasingly difficult to come by. When Ruth was 14, she was conscripted to do forced labor, and she, her mother, and sister were all summoned to appear before the Gestapo. They all avoided deportation by the narrowest of margins.

This action concerned her mother, who decided that the time had come for them to go into hiding. She chose a wooden shed belonging to a Nazi called Leo Lindenberg, who was attracted to her.

Ruth recalls not feeling very safe living in the shed on an allotment south of Berlin, but it was better than risking residing in the town.

They removed the yellow Star of David, as this would have caused problems for Leo Lindenberg. The story they gave out was that the Allied bombing of Berlin had destroyed their flat. This was a common thing, so the tale attracted no attention.

It was very hard living in the shed, for it had no heating, water, or electricity. Winter temperatures fell to minus ten degrees, and with no way to heat it the shed was just as cold inside. Food was scarce, and they lived on oatmeal and red turnips.

The grain was not processed, so they had to grind it with a coffee grinder and then sift it.

Shortly before the war ended, Ruth’s sister Eddi passed away after contracting diphtheria.

Leo Lindenberg and Ruth’s mother eventually got married. Out of gratitude to him for saving her and her mother, Ruth converted back to Christianity, but she still wears the Star of David as a pendant around her neck.

Ruth is confident that her father would not have condemned her conversion back to Christianity and her mother only wanted her daughter to live a happy life, so she did oppose her conversion either.

Ruth makes the point that God was with her during the darkest days of her life, but that does not mean that she is an avid church-goer today.

She feels the presence of God in nature, and she gives thanks for him sparing her during 90 years on this earth.

Ruth feels it is vital for her to share her story with the younger generation. She hopes to show them that although there may be difficulties in living in a democracy where everyone has their own opinion of how things should be, living under a dictatorial rule is even worse.

On the pavement of the house where she grew up is a small brass plaque set into the pavement.

The polished plaque, about the size of a cobblestone, is inscribed with her father’s name and the date that he was killed at Auschwitz.

One of many tiny Holocaust memorials called Stolperstein or Stumbling Stones, the plaque is a way of honoring her father since he has no grave and no headstone.

Read another story from us: The Rab Concentration Camp – A Disturbingly ‘Forgotten’ Piece of History

For all the difficulties that Ruth has lived through she is amazingly free of bitterness, but she is concerned with the rise of right-wing fervor in Europe. She is hopeful that humankind learned something from the Nazi era and that the mass slaughter from that time will never be repeated.